Public Domain Text: Pirates by E. F. Benson

“Pirates” was first published in Hutchinson’s Magazine in October 1928. It’s the story of a middle-aged businessman who becomes gradually more and more obsessed with returning to the house he lived in as a child.

Although some of E. F. Benson’s stories are pretty dark and spooky, this one is not. It certainly has a supernatural focus but is unlikely to cause readers to get goosebumps or feel the hair standing up on the back of their necks. If that’s what you want, I suggest you read one of the author’s darker tales such as Caterpillars or Bagnell Terrace instead.

About E. F. Benson

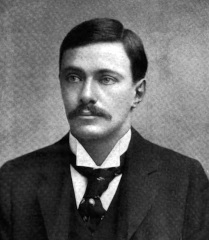

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

Pirates

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

For many years this project of sometime buying back the house had simmered in Peter Graham’s mind, but whenever he actually went into the idea with practical intention, stubborn reasons had presented themselves to deter him. In the first place it was very far off from his work, down in the heart of Cornwall, and it would be impossible to think of going there just for week-ends, and if he established himself there for longer periods what on earth would he do with himself in that soft remote Lotus-land? He was a busy man who, when at work, liked the diversion of his club and of the theatres in the evening, but he allowed himself few holidays away from the City, and those were spent on salmon river or golf links with some small party of solid and like-minded friends. Looked at in these lights, the project bristled with objections.

Yet through all these years, forty of them now, which had ticked away so imperceptibly, the desire to be at home again at Lescop had always persisted, and from time to time it gave him shrewd little unexpected tugs, when his conscious mind was in no way concerned with it. This desire, he was well aware, was of a sentimental quality, and often he wondered at himself that he, who was so well-armoured in the general jostle of the world against that type of emotion, should have just this one joint in his harness. Not since he was sixteen had he set eyes on the place, but the memory of it was more vivid than that of any other scene of subsequent experience. He had married since then, he had lost his wife, and though for many months after that he had felt horribly lonely, the ache of that loneliness had ceased, and now, if he had ever asked himself the direct question, he would have confessed that bachelor existence was more suited to him than married life had ever been. It had not been a conspicuous success, and he never felt the least temptation to repeat the experiment.

But there was another loneliness which neither married life nor his keen interest in his business had ever extinguished, and this was directly connected with his desire for that house on the green slope of the hills above Truro. For only seven years had he lived there, the youngest but one of a family of five children, and now out of all that gay company he alone was left. One by one they had dropped off the stem of life, but as each in turn went into this silence, Peter had not missed them very much: his own life was too occupied to give him time really to miss anybody, and he was too vitally constituted to do otherwise than look forwards.

None of that brood of children except himself, and he childless, had married, and now when he was left without intimate tie of blood to any living being, a loneliness had gathered thickly round him. It was not in any sense a tragic or desperate loneliness: he had no wish to follow them on the unverified and unlikely chance of finding them all again. Also, he had no use for any disembodied existence: life meant to him flesh and blood and material interests and activities, and he could form no conception of life apart from such. But sometimes he ached with this dull gnawing ache of loneliness, which is worse than all others, when he thought of the stillness that lay congealed like clear ice over these young and joyful years when Lescop had been so noisy and alert and full of laughter, with its garden resounding with games, and the house with charades and hide-and-seek and multitudinous plans. Of course there had been rows and quarrels and disgraces, hot enough at the time, but now there was no one to quarrel with. “You can’t really quarrel with people whom you don’t love,” thought Peter, “because they don’t matter….” Yet it was ridiculous to feel lonely; it was even more than ridiculous, it was weak, and Peter had the kindly contempt of a successful and healthy and unemotional man for weaknesses of that kind. There were so many amusing and interesting things in the world, he had so many irons in the fire to be beaten, so to speak, into gold when he was working, and so many palatable diversions when he was not (for he still brought a boyish enthusiasm to work and play alike), that there was no excuse for indulging in sentimental sterilities. So, for months together, hardly a stray thought would drift towards the remote years lived in the house on the hill-side above Truro.

He had lately become chairman of the board of that new and highly promising company, the British Tin Syndicate. Their property included certain Cornish mines which had been previously abandoned as non-paying propositions, but a clever mineralogical chemist had recently invented a process by which the metal could be extracted far more cheaply than had hitherto been possible. The British Tin Syndicate had bought the patent, and having acquired these derelict Cornish mines was getting very good results from ore that had not been worth treating. Peter had very strong opinions as to the duty of a chairman to make himself familiar with the practical side of his concerns, and was now travelling down to Cornwall to make a personal inspection of the mines where this process was at work. He had with him certain technical reports which he had received to read during the uninterrupted hours of his journey, and it was not till his train had left Exeter behind that he finished his perusal of them, and, putting them back in his despatch-case, turned his eye at the swiftly passing panorama of travel. It was many years since he had been to the West Country, and now with the thrill of vivid recognition he found the red cliffs round Dawlish, interspersed between stretches of sunny sea-beach, startlingly familiar. Surely he must have seen them quite lately, he thought to himself, and then, ransacking his memory, he found it was forty years since he had looked at them, travelling back to Eton from his last holidays at Lescop. The intense sharp-cut impressions of youth!

His destination to-night was Penzance, and now, with a strangely keen sense of expectation, he remembered that just before reaching Truro station the house on the hill was visible from the train, for often on these journeys to and from school he had been all eyes to catch the first sight of it and the last. Trees perhaps would have grown up and intervened, but as they ran past the station before Truro he shifted across to the other side of the carriage, and once more looked out for that glimpse…. There it was, a mile away across the valley, with its grey stone front and the big beech-tree screening one end of it, and his heart leaped as he saw it. Yet what use was the house to him now? It was not the stones and the bricks of it, nor the tall hay-fields below it, nor the tangled garden behind that he wanted, but the days when he had lived in it. Yet he leaned from the window till a cutting extinguished the view of it, feeling that he was looking at a photograph that recalled some living presence. All those who had made Lescop dear and still vivid had gone, but this record remained, like the image on the plate…. And then he smiled at himself with a touch of contempt for his sentimentality.

The next three days were a whirl of enjoyable occupation: tin-mines in the concrete were new to Peter, and he absorbed himself in these, as in some new game or ingenious puzzle. He went down the shafts of mines which had been opened again, he inspected the new chemical process, seeing it at work and checking the results, he looked into running expenses, comparing them with the value of the metal recovered. Then, too, there was substantial traces of silver in some of these ores, and he went eagerly into the question as to whether it would pay to extract it. Certainly even the mines which had previously been closed down ought to yield a decent dividend with this process, while those where the lode was richer would vastly increase their profits. But economy, economy…. Surely it would save in the end, though at a considerable capital expenditure now, to lay a light railway from the works to the rail-head instead of employing these motor-lorries. There was a piece of steep gradient, it was true, but a small detour, with a trestle-bridge over the stream, would avoid that.

He walked over the proposed route with the engineer and scrambled about the stream-bank to find a good take-off for his trestle-bridge. And all the time at the back of his head, in some almost subconscious region of thought, were passing endless pictures of the house and the hill, its rooms and passages, its fields and garden, and with them, like some accompanying tune, ran that ache of loneliness. He felt that he must prowl again about the place: the owner, no doubt, if he presented himself, would let him just stroll about alone for half an hour. Thus he would see it all altered and overscored by the life of strangers living there, and the photograph would fade into a mere blur and then blankness. Much better that it should.

It was in this intention that, having explored every avenue for dividends on behalf of his company, he left Penzance by an early morning train in order to spend a few hours in Truro and go up to London later in the day. Hardly had he emerged from the station when a crowd of memories, forty years old, but more vivid than any of those of the last day or two, flocked round him with welcome for his return. There was the level-crossing and the road leading down to the stream where his sister Sybil and he had caught a stickleback for their aquarium, and across the bridge over it was the lane sunk deep between high crumbling banks that led to a footpath across the fields to Lescop. He knew exactly where was that pool with long ribands of water-weed trailing and waving in it, which had yielded them that remarkable fish: he knew how campions red and white would be in flower on the lane-side, and in the fields the meadow-orchis. But it was more convenient to go first into the town, get his lunch at the hotel, and to make enquiries from a house-agent as to the present owner of Lescop; perhaps he would walk back to the station for his afternoon train by that short cut.

Thick now as flowers on the steppe when spring comes, memories bright and fragrant shot up round him. There was the shop where he had taken his canary to be stuffed (beautiful it looked!): and there was the shop of the “undertaker and cabinet-maker,” still with the same name over the door, where on a memorable birthday, on which his amiable family had given him, by request, the tokens of their good-will in cash, he had ordered a cabinet with five drawers and two trays, varnished and smelling of newly cut wood, for his collection of shells. There was a small boy in jersey and flannel trousers looking in at the window now, and Peter suddenly said to himself, “Good Lord, how like I used to be to that boy: same kit, too.” Strikingly like indeed he was, and Peter, curiously interested, started to cross the street to get a nearer look at him. But it was market-day, a drove of sheep delayed him, and when he got across the small boy had vanished among the passengers. Farther along was a dignified house-front with a flight of broad steps leading up to it, once the dreaded abode of Mr. Tuck, dentist. There was a tall girl standing outside it now, and again Peter involuntarily said to himself, “Why, that girl’s wonderfully like Sybil!” But before he could get more than a glimpse of her, the door was opened and she passed in, and Peter was rather vexed to find that there was no longer a plate on the door indicating that Mr. Tuck was still at his wheel. At the end of the street was the bridge over the Fal just below which they used so often to take a boat for a picnic on the river. There was a jolly family party setting off just now from the quay, three boys, he noticed, and a couple of girls, and a woman of young middle-age. Quickly they dropped downstream and went forth, and with half a sigh he said to himself, “Just our number with Mamma.”

He went to the Red Lion for his lunch: that was new ground and uninteresting, for he could not recall having set foot in that hostelry before. But as he munched his cold beef there was some great fantastic business going on deep down in his brain: it was trying to join up (and it believed it could) that boy outside the cabinet-maker’s, that girl on the threshold of the house once Mr. Tuck’s, and that family party starting for their picnic on the river. It was in vain that he told himself that neither the boy nor the girl nor the picnic-party could possibly have anything to do with him: as soon as his attention relaxed that burrowing underground chase, as of a ferret in a rabbit-hole, began again…. And then Peter gave a gasp of sheer amazement, for he remembered with clear-cut distinctness how on the morning of that memorable birthday, he and Sybil started earlier than the rest from Lescop, he on the adorable errand of ordering his cabinet, she for a dolorous visit to Mr. Tuck. The others followed half an hour later for a picnic on the Fal to celebrate the great fact that his age now required two figures (though one was a nought) for expression. “It’ll be ninety years, darling,” his mother had said, “before you want a third one, so be careful of yourself.”

Peter was almost as excited when this momentous memory burst on him as he had been on the day itself. Not that it meant anything, he said to himself, as there’s nothing for it to mean. But I call it odd. It’s as if something from those days hung about here still.

He finished his lunch quickly after that, and went to the house agent’s to make his enquiries. Nothing could be easier than that he should prowl about Lescop, for the house had been untenanted for the last two years. No card “to view” was necessary, but here were the keys: there was no caretaker there.

“But the house will be going to rack and ruins,” said Peter indignantly. “Such a jolly house, too. False economy not to put a caretaker in. But of course it’s no business of mine. You shall have the keys back during the afternoon: I’ll walk up there now.”

“Better take a taxi, sir,” said the man. “A hot day, and a mile and a half up a steep hill.”

“Oh, nonsense,” said Peter. “Barely a mile. Why, my brother and I used often to do it in ten minutes.”

It occurred to him that these athletic feats of forty years ago would probably not interest the modern world.

Pyder Street was as populous with small children as ever, and perhaps a little longer and steeper than it used to be. Then turning off to the right among strange new-built suburban villas he passed into the well-known lane, and in five minutes more had come to the gate leading into the short drive up to the house. It drooped on its hinges, he must lift it off the latch, sidle through and prop it in place again. Overgrown with grass and weeds was the drive, and with another spurt of indignation he saw that the stile to the pathway across the field was broken down and had dragged the wires of the fence with it. And then he came to the house itself, and the creepers trailed over the windows, and, unlocking the door, he stood in the hall with its discoloured ceiling and patches of mildew growing on the damp walls. Shabby and ashamed it looked, the paint perished from the window-sashes, the panes dirty, and in the air the sour smell of chambers long unventilated. And yet the spirit of the house was there still, though melancholy and reproachful, and it followed him wearily from room to room—”You are Peter, aren’t you?” it seemed to say. “You’ve just come to look at me, I see and not to stop. But I remember the jolly days just as well as you….” From room to room he went, dining-room, drawing-room, his mother’s sitting-room, his father’s study: then upstairs to what had been the school-room in the days of governesses, and had then been turned over to the children for a play-room. Along the passage was the old nursery and the night-nursery, and above that attic-rooms, to one of which, as his own exclusive bedroom, he had been promoted when he went to school. The roof of it had leaked, there was a brown-edged stain on the sagging ceiling just above where his bed had been. “A nice state to let my room get into,” muttered Peter. “How am I to sleep underneath that drip from the roof? Too bad!”

The vividness of his own indignation rather startled him. He had really felt himself to be not a dual personality, but the same Peter Graham at different periods of his existence. One of them, the chairman of the British Tin Syndicate, had protested against young Peter Graham being put to sleep in so damp and dripping a room, and the other (oh, the ecstatic momentary glimpse of him!) was indeed young Peter back in his lovely attic again, just home from school and now looking round with eager eyes to convince himself of that blissful reality, before bouncing downstairs again to have tea in the children’s room. What a lot of things to ask about! How were his rabbits, and how were Sybil’s guinea-pigs, and had Violet learned that song “Oh ’tis nothing but a shower,” and were the wood-pigeons building again in the lime-tree? All these topics were of the first importance….

Peter Graham the elder sat down on the window-seat. It overlooked the lawn, and just opposite was the lime-tree, a drooping lime making a green cave inside the skirt of its lower branches, but with those above growing straight, and he heard the chuckling coo of the wood-pigeons coming from it. They were building there again then: that question of young Peter’s was answered.

“Very odd that I should just be thinking of that,” he said to himself: somehow there was no gap of years between him and young Peter, for his attic bridged over the decades which in the clumsy material reckoning of time intervened between them. Then Peter the elder seemed to take charge again.

The house was a sad affair, he thought: it gave him a stab of loneliness to see how decayed was the theatre of their joyful years, and no evidence of newer life, of the children of strangers and even of their children’s children growing up here could have overscored the old sense of it so effectually. He went out of young Peter’s room and paused on the landing: the stairs led down in two short flights to the story below, and now for the moment he was young Peter again, reaching down with his hand along the banisters, and preparing to take the first flight in one leap. But then old Peter saw it was an impossible feat for his less supple joints.

Well, there was the garden to explore, and then he would go back to the agent’s and return the keys. He no longer wanted to take that short cut down the steep hill to the station, passing the pool where Sybil and he had caught the stickleback, for his whole notion, sometimes so urgent, of coming back here, had wilted and withered. But he would just walk about the garden for ten minutes, and as he went with sedate step downstairs, memories of the garden, and of what they all did there began to invade him. There were trees to be climbed, and shrubberies—one thicket of syringa particularly where goldfinches built—to be searched for nests and moths, but above all there was that game they played there, far more exciting than lawn-tennis or cricket in the bumpy field (though that was exciting enough) called Pirates. There was a summer-house, tiled and roofed and of solid walls at the top of the garden, and that was ‘home’ or ‘Plymouth Sound,’ and from there ships (children that is) set forth at the order of the Admiral to pick a trophy without being caught by the Pirates. There were two Pirates who hid anywhere in the garden and jumped out, and (counting the Admiral who, after giving his orders, became the flagship) three ships, which had to cruise to orchard or flower-bed or field and bring safely home a trophy culled from the ordained spot. Once, Peter remembered, he was flying up the winding path to the summer-house with a pirate close on his heels, when he fell flat down, and the humane pirate leaped over him for fear of treading on him, and fell down too. So Peter got home, because Dick had fallen on his face and his nose was bleeding.

“Good Lord, it might have happened yesterday,” thought Peter. “And Harry called him a bloody pirate, and Papa heard and thought he was using shocking language till it was explained to him.”

The garden was even worse than the house, neglected utterly and rankly overgrown, and to find the winding path at all, Peter had to push through briar and thicket. But he persevered and came out into the rose-garden at the top, and there was Plymouth Sound with roof collapsed and walls bulging, and moss growing thick between the tiles of the floor.

“But it must be repaired at once,” said Peter aloud…. “What’s that?” He whisked round towards the bushes through which he had pushed his way, for he had heard a voice, faint and far off coming from there, and the voice was familiar to him, though for thirty years it had been dumb. For it was Violet’s voice which had spoken and she had said, “Oh, Peter: here you are!”

He knew it was her voice, and he knew the utter impossibility of it. But it frightened him, and yet how absurd it was to be frightened, for it was only his imagination, kindled by old sights and memories, that had played him a trick. Indeed, how jolly even to have imagined that he had heard Violet’s voice again.

“Vi!” he called aloud, but of course no one answered. The wood-pigeons were cooing in the lime, there was a hum of bees and a whisper of wind in the trees, and all round the soft enchanted Cornish air, laden with dream-stuff.

He sat down on the step of the summer-house, and demanded the presence of his own common sense. It had been an uncomfortable afternoon, he was vexed at this ruin of neglect into which the place had fallen, and he did not want to imagine these voices calling to him out of the past, or to see these odd glimpses which belonged to his boyhood. He did not belong any more to that epoch over which grasses waved and headstones presided, and he must be quit of all that evoked it, for, more than anything else, he was director of prosperous companies with big interests dependent on him. So he sat there for a calming five minutes, defying Violet, so to speak, to call to him again. And then, so unstable was his mood to-day, that presently he was listening for her. But Violet was always quick to see when she was not wanted, and she must have gone, to join the others.

He retraced his way, fixing his mind on material environments. The golden maple at the head of the walk, a sapling like himself when last he saw it, had become a stout-trunked tree, the shrub of bay a tall column of fragrant leaf, and just as he passed the syringa, a goldfinch dropped out of it with dipping flight. Then he was back at the house again where the climbing fuchsia trailed its sprays across the window of his mother’s room and hot thick scent (how well-remembered!) spilled from the chalices of the great magnolia.

“A mad notion of mine to come and see the house again,” he said to himself. “I won’t think about it any more: it’s finished. But it was wicked not to look after it.”

He went back into the town to return the keys to the house-agent.

“Much obliged to you,” he said. “A pleasant house, when I knew it years ago. Why was it allowed to go to ruin like that?”

“Can’t say, sir,” said the man. “It has been let once or twice in the last ten years, but the tenants have never stopped long. The owner would be very pleased to sell it.”

An idea, fanciful, absurd, suddenly struck Peter.

“But why doesn’t he live there?” he asked. “Or why don’t the tenants stop long? Was there something they didn’t like about it? Haunted: anything of that sort? I’m not going to take it or purchase it: so that won’t put me off.”

The man hesitated a moment.

“Well, there were stories,” he said, “if I may speak confidentially. But all nonsense, of course.”

“Quite so,” said Peter. “You and I don’t believe in such rubbish. I wonder now: was it said that children’s voices were heard calling in the garden?”

The discretion of a house-agent reasserted itself.

“I can’t say, sir, I’m sure,” he said. “All I know is that the house is to be had very cheap. Perhaps you would take our card.”

Peter arrived back in London late that night. There was a tray of sandwiches and drinks waiting for him, and having refreshed himself, he sat smoking awhile thinking of his three days’ work in Cornwall at the mines: there must be a directors’ meeting as soon as possible to consider his suggestions. Then he found himself staring at the round rosewood table where his tray stood. It had been in his mother’s sitting-room at Lescop, and the chair in which he sat, a fine Stuart piece, had been his father’s chair at the dinner-table, and that book-case had stood in the hall, and his Chippendale card-table … he could not remember exactly where that had been. That set of Browning’s poems had been Sybil’s: it was from the shelves in the children’s room. But it was time to go to bed, and he was glad he was not to sleep in young Peter’s attic.

It is doubtful whether, if once an idea has really thrown out roots in a man’s mind, he can ever extirpate it. He can cut off its sprouting suckers, he can nip off the buds it bears, or, if they come to maturity, destroy the seed, but the roots defy him. If he tugs at them something breaks, leaving a vital part still embedded, and it is not long before some fresh evidence of its vitality pushes up above the ground where he least expected it. It was so with Peter now: in the middle of some business-meeting, the face of one of his co-directors reminded him of that of the coachman at Lescop; if he went for a week-end of golf to the Dormy House at Rye, the bow-window of the billiard-room was in shape and size that of the drawing-room there, and the bank of gorse by the tenth green was no other than the clump below the tennis-court: almost he expected to find a tennis ball there when he had need to search it. Whatever he did, wherever he went, something called him from Lescop, and in the evening when he returned home, there was the furniture, more of it than he had realized, asking to be restored there: rugs and pictures and books, the silver on his table all joined in the mute appeal. But Peter stopped his ears to it: it was a senseless sentimentality, and a purely materialistic one to imagine that he could recapture the life over which so many years had flowed, and in which none of the actors but himself remained, by restoring to the house its old amenities and living there again. He would only emphasize his own loneliness by the visible contrast of the scene, once so alert and populous, with its present emptiness. And this “butting-in” (so he expressed it) of materialistic sentimentality only confirmed his resolve to have done with Lescop. It had been a bitter sight but tonic, and now he would forget it.

Yet even as he sealed his resolution, there would come to him, blown as a careless breeze from the west, the memory of that boy and girl he had seen in the town, of the gay family starting for their river-picnic, of the faint welcoming call to him from the bushes in the garden, and, most of all, of the suspicion that the place was supposed to be haunted. It was just because it was haunted that he longed for it, and the more savagely and sensibly he assured himself of the folly of possessing it, the more he yearned after it, and constantly now it coloured his dreams. They were happy dreams; he was back there with the others, as in old days, children again in holiday time, and like himself they loved being at home there again, and they made much of Peter because it was he who had arranged it all. Often in these dreams he said to himself ‘I have dreamed this before, and then I woke and found myself elderly and lonely again, but this time it is real!’

The weeks passed on, busy and prosperous, growing into months, and one day in the autumn, on coming home from a day’s golf, Peter fainted. He had not felt very well for some time, he had been languid and easily fatigued, but with his robust habit of mind he had labelled such symptoms as mere laziness, and had driven himself with the whip. But now it might be as well to get a medical overhauling just for the satisfaction of being told there was nothing the matter with him. The pronouncement was not quite that….

“But I simply can’t,” he said. “Bed for a month and a winter of loafing on the Riviera! Why, I’ve got my time filled up till close on Christmas, and then I’ve arranged to go with some friends for a short holiday. Besides, the Riviera’s a pestilent hole. It can’t be done. Supposing I go on just as usual: what will happen?”

Dr. Dufflin made a mental summary of his wilful patient.

“You’ll die, Mr. Graham,” he said cheerfully. “Your heart is not what it should be, and if you want it to do its work, which it will for many years yet, if you’re sensible, you must give it rest. Of course, I don’t insist on the Riviera: that was only a suggestion for I thought you would probably have friends there, who would help to pass the time for you. But I do insist on some mild climate, where you can loaf out of doors. London with its frosts and fogs would never do.”

Peter was silent for a moment.

“How about Cornwall?” he asked.

“Yes, if you like. Not the north coast of course.”

“I’ll think it over,” said Peter. “There’s a month yet.”

Peter knew that there was no need for thinking it over. Events were conspiring irresistibly to drive him to that which he longed to do, but against which he had been struggling, so fantastic was it, so irrational. But now it was made easy for him to yield and his obstinate colours came down with a run. A few telegraphic exchanges with the house-agent made Lescop his, another gave him the address of a reliable builder and decorator, and with the plans of the house, though indeed there was little need of them, spread out on his counterpane, Peter issued urgent orders. All structural repairs, leaking roofs and dripping ceilings, rotted woodwork and crumbling plaster must be tackled at once, and when that was done, painting and papering followed. The drawing-room used to have a Morris-paper; there were spring flowers on it, blackthorn, violets, and fritillaries, a hateful wriggling paper, so he thought it, but none other would serve. The hall was painted duck-egg green, and his mother’s room was pink, “a beastly pink, tell them,” said Peter to his secretary, “with a bit of blue in it: they must send me sample by return of post, big pieces, not snippets….” Then there was furniture: all the furniture in the house here which had once been at Lescop must go back there. For the rest, he would send down some stuff from London, bedroom appurtenances, and linen and kitchen utensils: he would see to carpets when he got there. Spare bedrooms could wait; just four servants’ rooms must be furnished, and also the attic which he had marked on the plan, and which he intended to occupy himself. But no one must touch the garden till he came: he would superintend that himself, but by the middle of next month there must be a couple of gardeners ready for him.

“And that’s all,” said Peter, “just for the present.” “All?” he thought, as, rather bored with the direction of matters that usually ran themselves, he folded up his plans. “Why, it’s just the beginning: just underwriting.”

The month’s rest-cure was pronounced a success, and with strict orders not to exert mind or body, but to lie fallow, out of doors whenever possible, with quiet strolls and copious restings, Peter was allowed to go to Lescop, and on a December evening he saw the door opened to him and the light of welcome stream out on to his entry. The moment he set foot inside he knew, as by some interior sense, that he had done right, for it was not only the warmth and the ordered comfort restored to the deserted house that greeted him, but the firm knowledge that they whose loss made his loneliness were greeting him. That came in a flash, fantastic and yet soberly convincing; it was fundamental, everything was based on it. The house had been restored to its old aspect, and though he had ventured to turn the small attic next door to young Peter’s bedroom into a bathroom, “after all,” he thought, “it’s my house, and I must make myself comfortable. They don’t want bathrooms, but I do, and there it is.” There indeed it was, and there was electric light installed, and he dined, sitting in his father’s chair, and then pottered from room to room, drinking in the old friendly atmosphere, which was round him wherever he went, for They were pleased. But neither voice nor vision manifested that, and perhaps it was only his own pleasure at being back that he attributed to them. But he would have loved a glimpse or a whisper, and from time to time, as he sat looking over some memoranda about the British Tin Syndicate, he peered into corners of the room, thinking that something moved there, and when a trail of creeper tapped against the window he got up and looked out. But nothing met his scrutiny but the dim starlight falling like dew on the neglected lawn. “They’re here, though,” he said to himself, as he let the curtain fall back.

The gardeners were ready for him next morning, and under his directions began the taming of the jungly wildness. And here was a pleasant thing, for one of them was the son of the cowman, Calloway, who had been here forty years ago, and he had childish memories still of the garden where with his father he used to come from the milking-shed to the house with the full pails. And he remembered that Sybil used to keep her guinea-pigs on the drying-ground at the back of the house. Now that he said that Peter remembered it too, and so the drying-ground all overgrown with brambles and rank herbage must be cleared.

“Iss, sure, nasty little vermin I thought them,” said Calloway the younger, “but ’twas here Miss Sybil had their hutches and a wired run for ’em. And a rare fuss there was when my father’s terrier got in and killed half of ’em, and the young lady crying over the corpses.”

That massacre of the innocents was dim to Peter; it must have happened in term-time when he was at school, and by the next holidays, to be sure, the prolific habits of her pets had gladdened Sybil’s mourning.

So the drying-ground was cleared and the winding path up the shrubbery to the summer-house which had been home to the distressed vessels pursued by pirates. This was being rebuilt now, the roof timbered up, the walls rectified and whitewashed, and the steps leading to it and its tiled floor cleaned of the encroaching moss. It was soon finished, and Peter often sat there to rest and read the papers after a morning of prowling and supervising in the garden, for an hour or two on his feet oddly tired him, and he would doze in the sunny shelter. But now he never dreamed about coming back to Lescop or of the welcoming presences. “Perhaps that’s because I’ve come,” he thought, “and those dreams were only meant to drive me. But I think they might show that they’re pleased: I’m doing all I can.”

Yet he knew they were pleased, for as the work in the garden progressed, the sense of them and their delight hung about the cleared paths as surely as the smell of the damp earth and the uprooted bracken which had made such trespass. Every evening Calloway collected the gleanings of the day, piling it on the bonfire in the orchard. The bracken flared, and the damp hazel stems fizzed and broke into flame, and the scent of the wood smoke drifted across to the house. And after some three weeks’ work all was done, and that afternoon Peter took no siesta in the summer-house, for he could not cease from walking through flower-garden and kitchen-garden and orchard now perfectly restored to their old order. A shower fell, and he sheltered under the lime where the pigeons built, and then the sun came out again, and in that gleam at the close of the winter day he took a final stroll to the bottom of the drive, where the gate now hung firm on even hinges. It used to take a long time in closing, if, as a boy, you let it swing, penduluming backwards and forwards with the latch of it clicking as it passed the hasp: and now he pulled it wide, and let go of it, and to and fro it went in lessening movement till at last it clicked and stayed. Somehow that pleased him immensely: he liked accuracy in details.

But there was no doubt he was very tired: he had an unpleasant sensation, too, as of a wire stretched tight across his heart, and of some thrumming going on against it. The wire dully ached, and this thrumming produced little stabs of sharp pain. All day he had been conscious of something of the sort, but he was too much taken up with the joy of the finished garden to heed little physical beckonings. A good long night would make him fit again, or, if not, he could stop in bed to-morrow. He went upstairs early, not the least anxious about himself, and instantly went to sleep. The soft night air pushed in at his open window, and the last sound that he heard was the tapping of the blind-tassel against the sash.

He woke very suddenly and completely, knowing that somebody had called him. The room was curiously bright, but not with the quality of moonlight; it was like a valley lying in shadow, while somewhere, a little way above it, shone some strong splendour of noon. And then he heard again his name called, and knew that the sound of the voice came in through the window. There was no doubt that Violet was calling him: she and the others were out in the garden.

“Yes, I’m coming,” he cried, and he jumped out of bed. He seemed—it was not odd—to be already dressed: he had on a jersey and flannel trousers, but his feet were bare and he slipped on a pair of shoes, and ran downstairs, taking the first short flight in one leap, like young Peter. The door of his mother’s room was open, and he looked in, and there she was, of course, sitting at the table and writing letters.

“Oh, Peter, how lovely to have you home again,” she said. “They’re all out in the garden, and they’ve been calling you, darling. But come and see me soon, and have a talk.”

Out he ran along the walk below the windows, and up the winding path through the shrubbery to the summer-house, for he knew they were going to play Pirates. He must hurry, or the pirates would be abroad before he got there, and as he ran, he called out:

“Oh, do wait a second: I’m coming.”

He scudded past the golden maple and the bay tree, and there they all were in the summer-house which was home. And he took a flying leap up the steps and was among them.

It was there that Calloway found him next morning. He must indeed have run up the winding path like a boy, for the new-laid gravel was spurned at long intervals by the toe-prints of his shoes.

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)