And No Bird Sings by E. F. Benson

“And No Bird Sings” is a short story by E. F. Benson. It was first published in Woman (magazine) in December 1926. “And No Bird Sings” was republished two years later in E. F. Benson’s short story collection, Spook Stories.

Since then, the story has also been featured in numerous mixed-author anthologies.

“And No Bird Sings” begins with a man visiting his friend who has recently inherited a country estate in Surrey.

When he arrives at the local train station, the man decides to walk to his friend’s manor house. It’s a pleasant day, and the house is only about one mile away.

The man’s route takes him through a dark and dreary wood, where he’s surprised by the lack of birds.

Like the birds, his friend’s dogs won’t go in the wood either and it’s soon clear something evil is lurking there. Something that thrives in the darkness and sucks the blood out of rabbits.

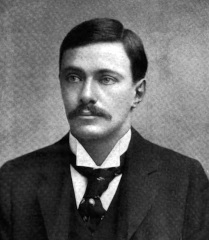

About E. F. Benson

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

And No Bird Sings

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

The red chimneys of the house for which I was bound were visible from just outside the station at which I had alighted, and, so the chauffeur told me, the distance was not more than a mile’s walk if I took the path across the fields. It ran straight till it came to the edge of that wood yonder, which belonged to my host, and above which his chimneys were visible. I should find a gate in the paling of this wood, and a track traversing it, which debouched close to his garden. So, in this adorable afternoon of early May, it seemed a waste of time to do other than walk through meadows and woods, and I set off on foot, while the motor carried my traps.

It was one of those golden days which every now and again leak out of Paradise and drip to earth. Spring had been late in coming, but now it was here with a burst, and the whole world was boiling with the sap of life. Never have I seen such a wealth of spring flowers, or such vividness of green, or heard such melodious business among the birds in the hedgerows; this walk through the meadows was a jubilee of festal ecstasy. And best of all, so I promised myself, would be the passage through the wood newly fledged with milky green that lay just ahead. There was the gate, just facing me, and I passed through it into the dappled lights and shadows of the grass-grown track.

Coming out of the brilliant sunshine was like entering a dim tunnel; one had the sense of being suddenly withdrawn from the brightness of the spring into some subaqueous cavern. The tree-tops formed a green roof overhead, excluding the light to a remarkable degree; I moved in a world of shifting obscurity. Presently, as the trees grew more scattered, their place was taken by a thick growth of hazels, which met over the path, and then, the ground sloping downwards, I came upon an open clearing, covered with bracken and heather, and studded with birches. But though now I walked once more beneath the luminous sky, with the sunlight pouring down, it seemed to have lost its effulgence. The brightness—was it some odd optical illusion?—was veiled as if it came through crêpe. Yet there was the sun still well above the tree-tops in an unclouded heaven, but for all that the light was that of a stormy winter’s day, without warmth or brilliance. It was oddly silent, too; I had thought that the bushes and trees would be ringing with the song of mating-birds, but listening, I could hear no note of any sort, neither the fluting of thrush or blackbird, nor the cheerful whirr of the chaffinch, nor the cooing wood-pigeon, nor the strident clamour of the jay. I paused to verify this odd silence; there was no doubt about it. It was rather eerie, rather uncanny, but I supposed the birds knew their own business best, and if they were too busy to sing it was their affair.

As I went on it struck me also that since entering the wood I had not seen a bird of any kind; and now, as I crossed the clearing, I kept my eyes alert for them, but fruitlessly, and soon I entered the further belt of thick trees which surrounded it. Most of them I noticed were beeches, growing very close to each other, and the ground beneath them was bare but for the carpet of fallen leaves, and a few thin bramble-bushes. In this curious dimness and thickness of the trees, it was impossible to see far to right or left of the path, and now, for the first time since I had left the open, I heard some sound of life. There came the rustle of leaves from not far away, and I thought to myself that a rabbit, anyhow, was moving. But somehow it lacked the staccato patter of a small animal; there was a certain stealthy heaviness about it, as if something much larger were stealing along and desirous of not being heard. I paused again to see what might emerge, but instantly the sound ceased. Simultaneously I was conscious of some faint but very foul odour reaching me, a smell choking and corrupt, yet somehow pungent, more like the odour of something alive rather than rotting. It was peculiarly sickening, and not wanting to get any closer to its source I went on my way.

Before long I came to the edge of the wood; straight in front of me was a strip of meadow-land, and beyond an iron gate between two brick walls, through which I had a glimpse of lawn and flower-beds. To the left stood the house, and over house and garden there poured the amazing brightness of the declining afternoon.

Hugh Granger and his wife were sitting out on the lawn, with the usual pack of assorted dogs: a Welsh collie, a yellow retriever, a fox-terrier, and a Pekinese. Their protest at my intrusion gave way to the welcome of recognition, and I was admitted into the circle. There was much to say, for I had been out of England for the last three months, during which time Hugh had settled into this little estate left him by a recluse uncle, and he and Daisy had been busy during the Easter vacation with getting into the house. Certainly it was a most attractive legacy; the house, through which I was presently taken, was a delightful little Queen Anne manor, and its situation on the edge of this heather-clad Surrey ridge quite superb. We had tea in a small panelled parlour overlooking the garden, and soon the wider topics narrowed down to those of the day and the hour. I had walked, had I, asked Daisy, from the station: did I go through the wood, or follow the path outside it?

The question she thus put to me was given trivially enough; there was no hint in her voice that it mattered a straw to her which way I had come. But it was quite clearly borne in upon me that not only she but Hugh also listened intently for my reply. He had just lit a match for his cigarette, but held it unapplied till he heard my answer. Yes, I had gone through the wood; but now, though I had received some odd impressions in the wood, it seemed quite ridiculous to mention what they were. I could not soberly say that the sunshine there was of very poor quality, and that at one point in my traverse I had smelt a most iniquitous odour. I had walked through the wood; that was all I had to tell them.

I had known both my host and hostess for a tale of many years, and now, when I felt that there was nothing except purely fanciful stuff that I could volunteer about my experiences there, I noticed that they exchanged a swift glance, and could easily interpret it. Each of them signalled to the other an expression of relief; they told each other (so I construed their glance) that I, at any rate, had found nothing unusual in the wood, and they were pleased at that. But then, before any real pause had succeeded to my answer that I had gone through the wood, I remembered that strange absence of bird-song and birds, and as that seemed an innocuous observation in natural history, I thought I might as well mention it.

“One odd thing struck me,” I began (and instantly I saw the attention of both riveted again), “I didn’t see a single bird or hear one from the time I entered the wood to when I left it.”

Hugh lit his cigarette.

“I’ve noticed that too,” he said, “and it’s rather puzzling. The wood is certainly a bit of primeval forest, and one would have thought that hosts of birds would have nested in it from time immemorial. But, like you, I’ve never heard or seen one in it. And I’ve never seen a rabbit there either.”

“I thought I heard one this afternoon,” said I. “Something was moving in the fallen beech leaves.”

“Did you see it?” he asked.

I recollected that I had decided that the noise was not quite the patter of a rabbit.

“No, I didn’t see it,” I said, “and perhaps it wasn’t one. It sounded, I remember, more like something larger.”

Once again and unmistakably a glance passed between Hugh and his wife, and she rose.

“I must be off,” she said. “Post goes out at seven, and I lazed all morning. What are you two going to do?”

“Something out of doors, please,” said I. “I want to see the domain.”

Hugh and I accordingly strolled out again with the cohort of dogs. The domain was certainly very charming; a small lake lay beyond the garden, with a reed bed vocal with warblers, and a tufted margin into which coots and moorhens scudded at our approach. Rising from the end of that was a high heathery knoll full of rabbit holes, which the dogs nosed at with joyful expectations, and there we sat for a while overlooking the wood which covered the rest of the estate. Even now in the blaze of the sun near to its setting, it seemed to be in shadow, though like the rest of the view it should have basked in brilliance, for not a cloud flecked the sky and the level rays enveloped the world in a crimson splendour. But the wood was grey and darkling. Hugh, also, I was aware, had been looking at it, and now, with an air of breaking into a disagreeable topic, he turned to me.

“Tell me,” he said, “does anything strike you about that wood?”

“Yes: it seems to lie in shadow.”

He frowned.

“But it can’t, you know,” he said. “Where does the shadow come from? Not from outside, for sky and land are on fire.”

“From inside, then?” I asked

He was silent a moment.

“There’s something queer about it,” he said at length. “There’s something there, and I don’t know what it is. Daisy feels it too; she won’t ever go into the wood, and it appears that birds won’t either. Is it just the fact that, for some unexplained reason, there are no birds in it that has set all our imaginations at work?”

I jumped up.

“Oh, it’s all rubbish,” I said. “Let’s go through it now and find a bird. I bet you I find a bird.”

“Sixpence for every bird you see,” said Hugh.

We went down the hillside and walked round the wood till we came to the gate where I had entered that afternoon. I held it open after I had gone in for the dogs to follow. But there they stood, a yard or so away, and none of them moved.

“Come on, dogs,” I said, and Fifi, the fox-terrier, came a step nearer and then with a little whine retreated again.

“They always do that,” said Hugh, “not one of them will set foot inside the wood. Look!”

He whistled and called, he cajoled and scolded, but it was no use. There the dogs remained, with little apologetic grins and signallings of tails, but quite determined not to come.

“But why?” I asked.

“Same reason as the birds, I suppose, whatever that happens to be. There’s Fifi, for instance, the sweetest-tempered little lady; once I tried to pick her up and carry her in, and she snapped at me. They’ll have nothing to do with the wood; they’ll trot round outside it and go home.”

We left them there, and in the sunset light which was now beginning to fade began the passage. Usually the sense of eeriness disappears if one has a companion, but now to me, even with Hugh walking by my side, the place seemed even more uncanny than it had done that afternoon, and a sense of intolerable uneasiness, that grew into a sort of waking nightmare, obsessed me. I had thought before that the silence and loneliness of it had played tricks with my nerves; but with Hugh here it could not be that, and indeed I felt that it was not any such notion that lay at the root of this fear, but rather the conviction that there was some presence lurking there, invisible as yet, but permeating the gathered gloom. I could not form the slighted idea of what it might be, or whether it was material or ghostly; all I could diagnose of it from my own sensations was that it was evil and antique.

As we came to the open ground in the middle of the wood, Hugh stopped, and though the evening was cool I noticed that he mopped his forehead.

“Pretty nasty,” he said. “No wonder the dogs don’t like it. How do you feel about it?”

Before I could answer, he shot out his hand, pointing to the belt of trees that lay beyond.

“What’s that?” he said in a whisper.

I followed his finger, and for one half-second thought I saw against the black of the wood some vague flicker, grey or faintly luminous. It waved as if it had been the head and forepart of some huge snake rearing itself, but it instantly disappeared, and my glimpse had been so momentary that I could not trust my impression.

“It’s gone,” said Hugh, still looking in the direction he had pointed; and as we stood there, I heard again what I had heard that afternoon, a rustle among the fallen beech-leaves. But there was no wind nor breath of breeze astir.

He turned to me.

“What on earth was it?” he said. “It looked like some enormous slug standing up. Did you see it?”

“I’m not sure whether I did or not,” I said. “I think I just caught sight of what you saw.”

“But what was it?” he said again. “Was it a real material creature, or was it—”

“Something ghostly, do you mean?” I asked.

“Something half-way between the two,” he said. “I’ll tell you what I mean afterwards, when we’ve got out of this place.”

The thing, whatever it was, had vanished among the trees to the left of where our path lay, and in silence we walked across the open till we came to where it entered tunnel-like among the trees. Frankly I hated and feared the thought of plunging into that darkness with the knowledge that not so far off there was something the nature of which I could not ever so faintly conjecture, but which, I now made no doubt, was that which filled the wood with some nameless terror. Was it material, was it ghostly, or was it (and now some inkling of what Hugh meant began to form itself into my mind) some being that lay on the borderland between the two? Of all the sinister possibilities that appeared the most terrifying.

As we entered the trees again I perceived that reek, alive and yet corrupt, which I had smelt before, but now it was far more potent, and we hurried on, choking with the odour that I now guessed to be not the putrescence of decay, but the living substance of that which crawled and reared itself in the darkness of the wood where no bird would shelter. Somewhere among those trees lurked the reptilian thing that defied and yet compelled credence.

It was a blessed relief to get out of that dim tunnel into the wholesome air of the open and the clear light of evening. Within doors, when we returned, windows were curtained and lamps lit. There was a hint of frost, and Hugh put a match to the fire in his room, where the dogs, still a little apologetic, hailed us with thumpings of drowsy tails.

“And now we’ve got to talk,” said he, “and lay our plans, for whatever it is that is in the wood, we’ve got to make an end of it. And, if you want to know what I think it is, I’ll tell you.”

“Go ahead,” said I.

“You may laugh at me, if you like,” he said, “but I believe it’s an elemental. That’s what I meant when I said it was a being half-way between the material and the ghostly. I never caught a glimpse of it till this afternoon; I only felt there was something horrible there. But now I’ve seen it, and it’s like what spiritualists and that sort of folk describe as an elemental. A huge phosphorescent slug is what they tell us of it, which at will can surround itself with darkness.”

Somehow, now safe within doors, in the cheerful light and warmth of the room, the suggestion appeared merely grotesque. Out there in the darkness of that uncomfortable wood something within me had quaked, and I was prepared to believe any horror, but now commonsense revolted.

“But you don’t mean to tell me you believe in such rubbish?” I said. “You might as well say it was a unicorn. What is an elemental, anyway? Who has ever seen one except the people who listen to raps in the darkness and say they are made by their aunts?”

“What is it then?” he asked.

“I should think it is chiefly our own nerves,” I said. “I frankly acknowledge I got the creeps when I went through the wood first, and I got them much worse when I went through it with you. But it was just nerves; we are frightening ourselves and each other.”

“And are the dogs frightening themselves and each other?” he asked. “And the birds?”

That was rather harder to answer; in fact I gave it up.

Hugh continued.

“Well, just for the moment we’ll suppose that something else, not ourselves, frightened us and the dogs and the birds,” he said, “and that we did see something like a huge phosphorescent slug. I won’t call it an elemental, if you object to that; I’ll call it It. There’s another thing, too, which the existence of It would explain.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Well, it is supposed to be some incarnation of evil, it is a corporeal form of the devil. It is not only spiritual, it is material to this extent that it can be seen bodily in form, and heard, and, as you noticed, smelt, and, God forbid, handled. It has to be kept alive by nourishment. And that explains perhaps why, every day since I have been here, I’ve found on that knoll we went up some half-dozen dead rabbits.”

“Stoats and weasels,” said I.

“No, not stoats and weasels. Stoats kill their prey and eat it. These rabbits have not been eaten; they’ve been drunk.”

“What on earth do you mean?” I asked.

“I examined several of them. There was just a small hole in their throats, and they were drained of blood. Just skin and bones, and a sort of grey mash of fibre, like, like the fibre of an orange which has been sucked. Also there was a horrible smell lingering on them. And was the thing you had a glimpse of like a stoat or a weasel?”

There came a rattle at the handle of the door.

“Not a word to Daisy,” said Hugh as she entered.

“I heard you come in,” she said. “Where did you go?”

“All round the place,” said I, “and came back through the wood. It is odd; not a bird did we see, but that is partly accounted for because it was dark.”

I saw her eyes search Hugh’s, but she found no communication there. I guessed that he was planning some attack on It next day, and he did not wish her to know that anything was afoot.

“The wood’s unpopular,” he said. “Birds won’t go there, dogs won’t go there, and Daisy won’t go there. I’m bound to say I share the feeling too, but having braved its terrors in the dark I’ve broken the spell.”

“All quiet, was it?” asked she.

“Quiet wasn’t the word for it. The smallest pin could have been heard dropping half a mile off.”

We talked over our plans that night after she had gone up to bed. Hugh’s story about the sucked rabbits was rather horrible, and though there was no certain connection between those empty rinds of animals and what we had seen, there seemed a certain reasonableness about it. But anything, as he pointed out, which could feed like that was clearly not without its material side—ghosts did not have dinner, and if it was material it was vulnerable.

Our plans, therefore, were very simple; we were going to tramp through the wood, as one walks up partridges in a field of turnips, each with a shot-gun and a supply of cartridges. I cannot say that I looked forward to the expedition, for I hated the thought of getting into closer quarters with that mysterious denizen of the woods; but there was a certain excitement about it, sufficient to keep me awake a long time, and when I got to sleep to cause very vivid and awful dreams.

The morning failed to fulfil the promise of the clear sunset; the sky was lowering and cloudy and a fine rain was falling. Daisy had shopping-errands which took her into the little town, and as soon as she had set off we started on our business. The yellow retriever, mad with joy at the sight of guns, came bounding with us across the garden, but on our entering the wood he slunk back home again.

The wood was roughly circular in shape, with a diameter perhaps of half a mile. In the centre, as I have said, there was an open clearing about a quarter of a mile across, which was thus surrounded by a belt of thick trees and copse a couple of hundred yards in breadth. Our plan was first to walk together up the path which led through the wood, with all possible stealth, hoping to hear some movement on the part of what we had come to seek. Failing that, we had settled to tramp through the wood at the distance of some fifty yards from each other in a circular track; two or three of these circuits would cover the whole ground pretty thoroughly. Of the nature of our quarry, whether it would try to steal away from us, or possibly attack, we had no idea; it seemed, however, yesterday to have avoided us.

Rain had been falling steadily for an hour when we entered the wood; it hissed a little in the tree-tops overhead; but so thick was the cover that the ground below was still not more than damp. It was a dark morning outside; here you would say that the sun had already set and that night was falling. Very quietly we moved up the grassy path, where our footfalls were noiseless, and once we caught a whiff of that odour of live corruption; but though we stayed and listened not a sound of anything stirred except the sibilant rain over our heads. We went across the clearing and through to the far gate, and still there was no sign.

“We’ll be getting into the trees then,” said Hugh. “We had better start where we got that whiff of it.”

We went back to the place, which was towards the middle of the encompassing trees. The odour still lingered on the windless air.

“Go on about fifty yards,” he said, “and then we’ll go in. If either of us comes on the track of it we’ll shout to each other.”

I walked on down the path till I had gone the right distance, signalled to him, and we stepped in among the trees.

I have never known the sensation of such utter loneliness. I knew that Hugh was walking parallel with me, only fifty yards away, and if I hung on my step I could faintly hear his tread among the beech leaves. But I felt as if I was quite sundered in this dim place from all companionship of man; the only live thing that lurked here was that monstrous mysterious creature of evil. So thick were the trees that I could not see more than a dozen yards in any direction; all places outside the wood seemed infinitely remote, and infinitely remote also everything that had occurred to me in normal human life. I had been whisked out of all wholesome experiences into this antique and evil place. The rain had ceased, it whispered no longer in the tree-tops, testifying that there did exist a world and a sky outside, and only a few drops from above pattered on the beech leaves.

Suddenly I heard the report of Hugh’s gun, followed by his shouting voice.

“I’ve missed it,” he shouted; “it’s coming in your direction.”

I heard him running towards me, the beech-leaves rustling, and no doubt his footsteps drowned a stealthier noise that was close to me. All that happened now, until once more I heard the report of Hugh’s gun, happened, I suppose, in less than a minute. If it had taken much longer I do not imagine I should be telling it to-day.

I stood there then, having heard Hugh’s shout, with my gun cocked, and ready to put to my shoulder, and I listened to his running footsteps. But still I saw nothing to shoot at and heard nothing. Then between two beech trees, quite close to me, I saw what I can only describe as a ball of darkness. It rolled very swiftly towards me over the few yards that separated me from it, and then, too late, I heard the dead beech-leaves rustling below it. Just before it reached me, my brain realised what it was, or what it might be, but before I could raise my gun to shoot at that nothingness, it was upon me. My gun was twitched out of my hand, and I was enveloped in this blackness, which was the very essence of corruption. It knocked me off my feet, and I sprawled flat on my back, and upon me, as I lay there, I felt the weight of this invisible assailant.

I groped wildly with my hands and they clutched something cold and slimy and hairy. They slipped off it, and next moment there was laid across my shoulder and neck something which felt like an india-rubber tube. The end of it fastened on to my neck like a snake, and I felt the skin rise beneath it. Again, with clutching hands, I tried to tear that obscene strength away from me, and as I struggled with it, I heard Hugh’s footsteps close to me through this layer of darkness that hid everything.

My mouth was free, and I shouted at him.

“Here, here!” I yelled “Close to you, where it is darkest.”

I felt his hands on mine, and that added strength detached from my neck that sucker that pulled at it. The coil that lay heavy on my legs and chest writhed and struggled and relaxed. Whatever it was that our four hands held, slipped out of them, and I saw Hugh standing close to me. A yard or two off, vanishing among the beech trunks, was that blackness which had poured over me. Hugh put up his gun, and with his second barrel fired at it.

The blackness dispersed, and there, wriggling and twisting like a huge worm lay what we had come to find. It was alive still, and I picked up my gun which lay by my side and fired two more barrels into it. The writhings dwindled into mere shudderings and shakings, and then it lay still.

With Hugh’s help I got to my feet, and we both reloaded before going nearer. On the ground there lay a monstrous thing, half-slug, half worm. There was no head to it; it ended in a blunt point with an orifice. In colour it was grey covered with sparse black hairs; its length I suppose was some four feet, its thickness at the broadest part was that of a man’s thigh, tapering towards each end. It was shattered by shot at its middle. There were stray pellets which had hit it elsewhere, and from the holes they had made there oozed not blood, but some grey viscous matter.

As we stood there some swift process of disintegration and decay began. It lost outline, it melted, it liquified, and in a minute more we were looking at a mass of stained and coagulated beech leaves. Again and quickly that liquor of corruption faded, and there lay at our feet no trace of what had been there. The overpowering odour passed away, and there came from the ground just the sweet savour of wet earth in springtime, and from above the glint of a sunbeam piercing the clouds. Then a sudden pattering among the dead leaves sent my heart into my mouth again, and I cocked my gun. But it was only Hugh’s yellow retriever who had joined us.

We looked at each other.

“You’re not hurt?” he said.

I held my chin up.

“Not a bit,” I said. “The skin’s not broken, is it?”

“No; only a round red mark. My God, what was it? What happened?”

“Your turn first,” said I. “Begin at the beginning.”

“I came upon it quite suddenly,” he said. “It was lying coiled like a sleeping dog behind a big beech. Before I could fire, it slithered off in the direction where I knew you were. I got a snap shot at it among the trees, but I must have missed, for I heard it rustling away. I shouted to you and ran after it. There was a circle of absolute darkness on the ground, and your voice came from the middle of it. I couldn’t see you at all, but I clutched at the blackness and my hands met yours. They met something else, too.”

We got back to the house and had put the guns away before Daisy came home from her shopping. We had also scrubbed and brushed and washed. She came into the smoking-room.

“You lazy folk,” she said. “It has cleared up, and why are you still indoors? Let’s go out at once.”

I got up.

“Hugh has told me you’ve got a dislike of the wood,” I said, “and it’s a lovely wood. Come and see; he and I will walk on each side of you and hold your hands. The dogs shall protect you as well.”

“But not one of them will go a yard into the wood,” said she.

“Oh yes, they will. At least we’ll try them. You must promise to come if they do.”

Hugh whistled them up, and down we went to the gate. They sat panting for it to be opened, and scuttled into the thickets in pursuit of interesting smells.

“And who says there are no birds in it?” said Daisy. “Look at that robin! Why, there are two of them. Evidently house-hunting.”

E. F. Benson (1867 — 1940)