Public Domain Text: Colonel Halifax’s Ghost Story by Sabine Baring-Gould

Colonel Halifax’s Ghost Story is a short story written by Sabine Baring-Gould.

The story was first published in The Illustrated English Magazine and was reprinted in Baring-Gould’s short story collection A Book of Ghosts (1904)

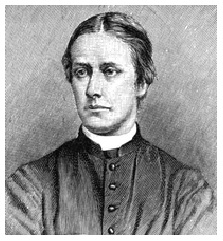

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

Colonel Halifax’s Ghost Story by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

I had just come back to England, after having been some years in India, and was looking forward to meet my friends, among whom there was none I was more anxious to see than Sir Francis Lynton. We had been at Eton together, and for the short time I had been at Oxford before entering the Army we had been at the same college. Then we had been parted. He came into the title and estates of the family in Yorkshire on the death of his grandfather—his father had predeceased—and I had been over a good part of the world. One visit, indeed, I had made him in his Yorkshire home, before leaving for India, of but a few days.

It will easily be imagined how pleasant it was, two or three days after my arrival in London, to receive a letter from Lynton saying he had just seen in the papers that I had arrived, and begging me to come down at once to Byfield, his place in Yorkshire.

“You are not to tell me,” he said, “that you cannot come. I allow you a week in which to order and try on your clothes, to report yourself at the War Office, to pay your respects to the Duke, and to see your sister at Hampton Court; but after that I shall expect you. In fact, you are to come on Monday. I have a couple of horses which will just suit you; the carriage shall meet you at Packham, and all you have got to do is to put yourself in the train which leaves King’s Cross at twelve o’clock.”

Accordingly, on the day appointed I started; in due time reached Packham, losing much time on a detestable branch line, and there found the dogcart of Sir Francis awaiting me. I drove at once to Byfield.

The house I remembered. It was a low, gabled structure of no great size, with old-fashioned lattice windows, separated from the park, where were deer, by a charming terraced garden.

No sooner did the wheels crunch the gravel by the principal entrance, than, almost before the bell was rung, the porch door opened, and there stood Lynton himself, whom I had not seen for so many years, hardly altered, and with all the joy of welcome beaming in his face. Taking me by both hands, he drew me into the house, got rid of my hat and wraps, looked me all over, and then, in a breath, began to say how glad he was to see me, what a real delight it was to have got me at last under his roof, and what a good time we would have together, like the old days over again.

He had sent my luggage up to my room, which was ready for me, and he bade me make haste and dress for dinner.

So saying, he took me through a panelled hall up an oak staircase, and showed me my room, which, hurried as I was, I observed was hung with tapestry, and had a large fourpost bed, with velvet curtains, opposite the window.

They had gone into dinner when I came down, despite all the haste I made in dressing; but a place had been kept for me next to Lady Lynton.

Besides my hosts, there were their two daughters, Colonel Lynton, a brother of Sir Francis, the chaplain, and some others whom I do not remember distinctly.

After dinner there was some music in the hall, and a game of whist in the drawing-room, and after the ladies had gone upstairs, Lynton and I retired to the smoking-room, where we sat up talking the best part of the night. I think it must have been near three when I retired. Once in bed, I slept so soundly that my servant’s entrance the next morning failed to arouse me, and it was past nine when I awoke.

After breakfast and the disposal of the newspapers, Lynton retired to his letters, and I asked Lady Lynton if one of her daughters might show me the house. Elizabeth, the eldest, was summoned, and seemed in no way to dislike the task.

The house was, as already intimated, by no means large; it occupied three sides of a square, the entrance and one end of the stables making the fourth side. The interior was full of interest—passages, rooms, galleries, as well as hall, were panelled in dark wood and hung with pictures. I was shown everything on the ground floor, and then on the first floor. Then my guide proposed that we should ascend a narrow twisting staircase that led to a gallery. We did as proposed, and entered a handsome long room or passage, leading to a small chamber at one end, in which my guide told me her father kept books and papers.

I asked if anyone slept in this gallery, as I noticed a bed, and fireplace, and rods, by means of which curtains might be drawn, enclosing one portion where were bed and fireplace, so as to convert it into a very cosy chamber.

She answered “No,” the place was not really used except as a playroom, though sometimes, if the house happened to be very full, in her great-grandfather’s time, she had heard that it had been occupied.

By the time we had been over the house, and I had also been shown the garden and the stables, and introduced to the dogs, it was nearly one o’clock. We were to have an early luncheon, and to drive afterwards to see the ruins of one of the grand old Yorkshire abbeys.

This was a pleasant expedition, and we got back just in time for tea, after which there was some reading aloud. The evening passed much in the same way as the preceding one, except that Lynton, who had some business, did not go down to the smoking-room, and I took the opportunity of retiring early in order to write a letter for the Indian mail, something having been said as to the prospect of hunting the next day.

I had finished my letter, which was a long one, together with two or three others, and had just got into bed when I heard a step overhead as of someone walking along the gallery, which I now knew ran immediately above my room. It was a slow, heavy, measured tread which I could hear getting gradually louder and nearer, and then as gradually fading away as it retreated into the distance.

I was startled for a moment, having been informed that the gallery was unused; but the next instant it occurred to me that I had been told it communicated with a chamber where Sir Francis kept books and papers. I knew he had some writing to do, and I thought no more on the matter.

I was down the next morning at breakfast in good time. “How late you were last night!” I said to Lynton, in the middle of breakfast. “I heard you overhead after one o’clock.”

Lynton replied rather shortly, “Indeed you did not, for I was in bed last night before twelve.”

“There was someone certainly moving overhead last night,” I answered, “for I heard his steps as distinctly as I ever heard anything in my life, going down the gallery.”

Upon which Colonel Lynton remarked that he had often fancied he had heard steps on his staircase, when he knew that no one was about. He was apparently disposed to say more, when his brother interrupted him somewhat curtly, as I fancied, and asked me if I should feel inclined after breakfast to have a horse and go out and look for the hounds. They met a considerable way off, but if they did not find in the coverts they should first draw, a thing not improbable, they would come our way, and we might fall in with them about one o’clock and have a run. I said there was nothing I should like better. Lynton mounted me on a very nice chestnut, and the rest of the party having gone out shooting, and the young ladies being otherwise engaged, he and I started about eleven o’clock for our ride.

The day was beautiful, soft, with a bright sun, one of those delightful days which so frequently occur in the early part of November.

On reaching the hilltop where Lynton had expected to meet the hounds no trace of them was to be discovered. They must have found at once, and run in a different direction. At three o’clock, after we had eaten our sandwiches, Lynton reluctantly abandoned all hopes of falling in with the hounds, and said we would return home by a slightly different route.

We had not descended the hill before we came on an old chalk quarry and the remains of a disused kiln.

I recollected the spot at once. I had been here with Sir Francis on my former visit, many years ago. “Why—bless me!” said I. “Do you remember, Lynton, what happened here when I was with you before? There had been men engaged removing chalk, and they came on a skeleton under some depth of rubble. We went together to see it removed, and you said you would have it preserved till it could be examined by some ethnologist or anthropologist, one or other of those dry-as-dusts, to decide whether the remains are dolichocephalous or brachycephalous, whether British, Danish, or—modern. What was the result?”

Sir Francis hesitated for a moment, and then answered: “It is true, I had the remains removed.”

“Was there an inquest?”

“No. I had been opening some of the tumuli on the Wolds. I had sent a crouched skeleton and some skulls to the Scarborough Museum. This I was doubtful about, whether it was a prehistoric interment—in fact, to what date it belonged. No one thought of an inquest.”

On reaching the house, one of the grooms who took the horses, in answer to a question from Lynton, said that Colonel and Mrs. Hampshire had arrived about an hour ago, and that, one of the horses being lame, the carriage in which they had driven over from Castle Frampton was to put up for the night. In the drawing-room we found Lady Lynton pouring out tea for her husband’s youngest sister and her husband, who, as we came in, exclaimed: “We have come to beg a night’s lodging.”

It appeared that they had been on a visit in the neighbourhood, and had been obliged to leave at a moment’s notice in consequence of a sudden death in the house where they were staying, and that, in the impossibility of getting a fly, their hosts had sent them over to Byfield.

“We thought,” Mrs. Hampshire went on to say, “that as we were coming here the end of next week, you would not mind having us a little sooner; or that, if the house were quite full, you would be willing to put us up anywhere till Monday, and let us come back later.”

Lady Lynton interposed with the remark that it was all settled; and then, turning to her husband, added: “But I want to speak to you for a moment.”

They both left the room together.

Lynton came back almost immediately, and, making an excuse to show me on a map in the hall the point to which we had ridden, said as soon as we were alone, with a look of considerable annoyance: “I am afraid we must ask you to change your room. Shall you mind very much? I think we can make you quite comfortable upstairs in the gallery, which is the only room available. Lady Lynton has had a good fire lit; the place is really not cold, and it will be for only a night or two. Your servant has been told to put your things together, but Lady Lynton did not like to give orders to have them actually moved before my speaking to you.”

I assured him that I did not mind in the very least, that I should be quite as comfortable upstairs, but that I did mind very much their making such a fuss about a matter of that sort with an old friend like myself.

Certainly nothing could look more comfortable than my new lodging when I went upstairs to dress. There was a bright fire in the large grate, an armchair had been drawn up beside it, and all my books and writing things had been put in, with a reading-lamp in the central position, and the heavy tapestry curtains were drawn, converting this part of the gallery into a room to itself. Indeed, I felt somewhat inclined to congratulate myself on the change. The spiral staircase had been one reason against this place having been given to the Hampshires. No lady’s long dress trunk could have mounted it.

Sir Francis was necessarily a good deal occupied in the evening with his sister and her husband, whom he had not seen for some time. Colonel Hampshire had also just heard that he was likely to be ordered to Egypt, and when Lynton and he retired to the smoking-room, instead of going there I went upstairs to my own room to finish a book in which I was interested. I did not, however, sit up long, and very soon went to bed.

Before doing so, I drew back the curtains on the rod, partly because I like plenty of air where I sleep, and partly also because I thought I might like to see the play of the moonlight on the floor in the portion of the gallery beyond where I lay, and where the blinds had not been drawn.

I must have been asleep for some time, for the fire, which I had left in full blaze, was gone to a few sparks wandering among the ashes, when I suddenly awoke with the impression of having heard a latch click at the further extremity of the gallery, where was the chamber containing books and papers.

I had always been a light sleeper, but on the present occasion I woke at once to complete and acute consciousness, and with a sense of stretched attention which seemed to intensify all my faculties. The wind had risen, and was blowing in fitful gusts round the house.

A minute or two passed, and I began almost to fancy I must have been mistaken, when I distinctly heard the creak of the door, and then the click of the latch falling back into its place. Then I heard a sound on the boards as of one moving in the gallery. I sat up to listen, and as I did so I distinctly heard steps coming down the gallery. I heard them approach and pass my bed. I could see nothing, all was dark; but I heard the tread proceeding towards the further portion of the gallery where were the uncurtained and unshuttered windows, two in number; but the moon shone through only one of these, the nearer; the other was dark, shadowed by the chapel or some other building at right angles. The tread seemed to me to pause now and again, and then continue as before.

I now fixed my eyes intently on the one illumined window, and it appeared to me as if some dark body passed across it: but what? I listened intently, and heard the step proceed to the end of the gallery and then return.

I again watched the lighted window, and immediately that the sound reached that portion of the long passage it ceased momentarily, and I saw, as distinctly as I ever saw anything in my life, by moonlight, a figure of a man with marked features, in what appeared to be a fur cap drawn over the brows.

It stood in the embrasure of the window, and the outline of the face was in silhouette; then it moved on, and as it moved I again heard the tread. I was as certain as I could be that the thing, whatever it was, or the person, whoever he was, was approaching my bed.

I threw myself back in the bed, and as I did so a mass of charred wood on the hearth fell down and sent up a flash of—I fancy sparks, that gave out a glare in the darkness, and by that—red as blood—I saw a face near me.

With a cry, over which I had as little control as the scream uttered by a sleeper in the agony of a nightmare, I called: “Who are you?”

There was an instant during which my hair bristled on my head, as in the horror of the darkness I prepared to grapple with the being at my side; when a board creaked as if someone had moved, and I heard the footsteps retreat, and again the click of the latch.

The next instant there was a rush on the stairs and Lynton burst into the room, just as he had sprung out of bed, crying: “For God’s sake, what is the matter? Are you ill?”

I could not answer. Lynton struck a light and leant over the bed. Then I seized him by the arm, and said without moving: “There has been something in this room—gone in thither.”

The words were hardly out of my mouth when Lynton, following the direction of my eyes, had sprung to the end of the corridor and thrown open the door there.

He went into the room beyond, looked round it, returned, and said: “You must have been dreaming.”

By this time I was out of bed.

“Look for yourself,” said he, and he led me into the little room. It was bare, with cupboards and boxes, a sort of lumber-place. “There is nothing beyond this,” said he, “no door, no staircase. It is a cul-de-sac.” Then he added: “Now pull on your dressing-gown and come downstairs to my sanctum.”

I followed him, and after he had spoken to Lady Lynton, who was standing with the door of her room ajar in a state of great agitation, he turned to me and said: “No one can have been in your room. You see my and my wife’s apartments are close below, and no one could come up the spiral staircase without passing my door. You must have had a nightmare. Directly you screamed I rushed up the steps, and met no one descending; and there is no place of concealment in the lumber-room at the end of the gallery.”

Then he took me into his private snuggery, blew up the fire, lighted a lamp, and said: “I shall be really grateful if you will say nothing about this. There are some in the house and neighbourhood who are silly enough as it is. You stay here, and if you do not feel inclined to go to bed, read—here are books. I must go to Lady Lynton, who is a good deal frightened, and does not like to be left alone.”

He then went to his bedroom.

Sleep, as far as I was concerned, was out of the question, nor do I think that Sir Francis or his wife slept much either.

I made up the fire, and after a time took up a book, and tried to read, but it was useless.

I sat absorbed in thoughts and questionings till I heard the servants stirring in the morning. I then went to my own room, left the candle burning, and got into bed. I had just fallen asleep when my servant brought me a cup of tea at eight o’clock.

At breakfast Colonel Hampshire and his wife asked if anything had happened in the night, as they had been much disturbed by noises overhead, to which Lynton replied that I had not been very well, and had an attack of cramp, and that he had been upstairs to look after me. From his manner I could see that he wished me to be silent, and I said nothing accordingly.

In the afternoon, when everyone had gone out, Sir Francis took me into his snuggery and said: “Halifax, I am very sorry about that matter last night. It is quite true, as my brother said, that steps have been heard about this house, but I never gave heed to such things, putting all noises down to rats. But after your experiences I feel that it is due to you to tell you something, and also to make to you an explanation. There is—there was—no one in the room at the end of the corridor, except the skeleton that was discovered in the chalk-pit when you were here many years ago. I confess I had not paid much heed to it. My archaeological fancies passed; I had no visits from anthropologists; the bones and skull were never shown to experts, but remained packed in a chest in that lumber-room. I confess I ought to have buried them, having no more scientific use for them, but I did not—on my word, I forgot all about them, or, at least, gave no heed to them. However, what you have gone through, and have described to me, has made me uneasy, and has also given me a suspicion that I can account for that body in a manner that had never occurred to me before.”

After a pause, he added: “What I am going to tell you is known to no one else, and must not be mentioned by you—anyhow, in my lifetime, You know now that, owing to the death of my father when quite young, I and my brother and sister were brought up here with our grandfather, Sir Richard. He was an old, imperious, short-tempered man. I will tell you what I have made out of a matter that was a mystery for long, and I will tell you afterwards how I came to unravel it. My grandfather was in the habit of going out at night with a young under-keeper, of whom he was very fond, to look after the game and see if any poachers, whom he regarded as his natural enemies, were about.

“One night, as I suppose, my grandfather had been out with the young man in question, and, returning by the plantations, where the hill is steepest, and not far from that chalk-pit you remarked on yesterday, they came upon a man, who, though not actually belonging to the country, was well known in it as a sort of travelling tinker of indifferent character, and a notorious poacher. Mind this, I am not sure it was at the place I mention; I only now surmise it. On the particular night in question, my grandfather and the keeper must have caught this man setting snares; there must have been a tussle, in the course of which as subsequent circumstances have led me to imagine, the man showed fight and was knocked down by one or other of the two—my grandfather or the keeper. I believe that after having made various attempts to restore him, they found that the man was actually dead.

“They were both in great alarm and concern—my grandfather especially. He had been prominent in putting down some factory riots, and had acted as magistrate with promptitude, and had given orders to the military to fire, whereby a couple of lives had been lost. There was a vast outcry against him, and a certain political party had denounced him as an assassin. No man was more vituperated; yet, in my conscience, I believe that he acted with both discretion and pluck, and arrested a mischievous movement that might have led to much bloodshed. Be that as it may, my impression is that he lost his head over this fatal affair with the tinker, and that he and the keeper together buried the body secretly, not far from the place where he was killed. I now think it was in the chalk-pit, and that the skeleton found years after there belonged to this man.”

“Good heavens!” I exclaimed, as at once my mind rushed back to the figure with the fur cap that I had seen against the window.

Sir Francis went on: “The sudden disappearance of the tramp, in view of his well-known habits and wandering mode of life, did not for some time excite surprise; but, later on, one or two circumstances having led to suspicion, an inquiry was set on foot, and among others, my grandfather’s keepers were examined before the magistrates. It was remembered afterwards that the under-keeper in question was absent at the time of the inquiry, my grandfather having sent him with some dogs to a brother-in-law of his who lived upon the moors; but whether no one noticed the fact, or if they did, preferred to be silent, I know not, no observations were made. Nothing came of the investigation, and the whole subject would have dropped if it had not been that two years later, for some reasons I do not understand, but at the instigation of a magistrate recently imported into the division, whom my grandfather greatly disliked, and who was opposed to him in politics, a fresh inquiry was instituted. In the course of that inquiry it transpired that, owing to some unguarded words dropped by the under-keeper, a warrant was about to be issued for his arrest. My grandfather, who had had a fit of the gout, was away from home at the time, but on hearing the news he came home at once. The evening he returned he had a long interview with the young man, who left the house after he had supped in the servants’ hall. It was observed that he looked much depressed. The warrant was issued the next day, but in the meantime the keeper had disappeared. My grandfather gave orders to all his own people to do everything in their power to assist the authorities in the search that was at once set on foot, but was unable himself to take any share in it.

“No trace of the keeper was found, although at a subsequent period rumours circulated that he had been heard of in America. But the man having been unmarried, he gradually dropped out of remembrance, and as my grandfather never allowed the subject to be mentioned in his presence, I should probably never have known anything about it but for the vague tradition which always attaches to such events, and for this fact: that after my grandfather’s death a letter came addressed to him from somewhere in the United States from someone—the name different from that of the keeper—but alluding to the past, and implying the presence of a common secret, and, of course, with it came a request for money. I replied, mentioning the death of Sir Richard, and asking for an explanation. I did get an answer, and it is from that that I am able to fill in so much of the story. But I never learned where the man had been killed and buried, and my next letter to the fellow was returned with ‘Deceased’ written across it. Somehow, it never occurred to me till I heard your story that possibly the skeleton in the chalk-pit might be that of the poaching tinker. I will now most assuredly have it buried in the churchyard.”

“That certainly ought to be done,” said I.

“And—” said Sir Francis, after a pause, “I give you my word. After the burial of the bones, and you are gone, I will sleep for a week in the bed in the gallery, and report to you if I see or hear anything. If all be quiet, then—well, you form your own conclusions.”

I left a day after. Before long I got a letter from my friend, brief but to the point: “All quiet, old boy; come again.”

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)