Public Domain Text: The Confession of Charles Linkworth by E. F. Benson

“The Confession of Charles Linkworth” was first published in Benson’s The Room in the Tower and Other Stories anthology (1912). It’s a fictional story concerning the events that happen after the execution of a murderer named Charles Linkworth, who murdered his mother-in-law to gain possession of her life savings of £500.

It’s impossible to justify taking a life for any sum of money and £500 may sound like a lot of money. However, Benson’s story does a good a good job of illustrating the rate of inflation in the UK. At the time of Benson wrote his Charles Linkworth story, £500 was a considerable sum. I’m not sure how things stand at the moment but, by 2017, the £500 from Benson’s era was the equivalent of around £40,000.

“The Confession of Charles Linkworth” is a ghost story. Far from being terrifying, it’s a tale of regret and the quest for redemption.

About E. F. Benson

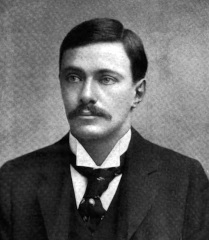

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

The Confession of Charles Linkworth

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

Dr. Teesdale had occasion to attend the condemned man once or twice during the week before his execution, and found him, as is often the case, when his last hope of life has vanished, quiet and perfectly resigned to his fate, and not seeming to look forward with any dread to the morning that each hour that passed brought nearer and nearer. The bitterness of death appeared to be over for him: it was done with when he was told that his appeal was refused. But for those days while hope was not yet quite abandoned, the wretched man had drunk of death daily. In all his experience the doctor had never seen a man so wildly and passionately tenacious of life, nor one so strongly knit to this material world by the sheer animal lust of living. Then the news that hope could no longer be entertained was told him, and his spirit passed out of the grip of that agony of torture and suspense, and accepted the inevitable with indifference. Yet the change was so extraordinary that it seemed to the doctor rather that the news had completely stunned his powers of feeling, and he was below the numbed surface, still knit into material things as strongly as ever. He had fainted when the result was told him, and Dr. Teesdale had been called in to attend him. But the fit was but transient, and he came out of it into full consciousness of what had happened.

The murder had been a deed of peculiar horror, and there was nothing of sympathy in the mind of the public towards the perpetrator. Charles Linkworth, who now lay under capital sentence, was the keeper of a small stationery store in Sheffield, and there lived with him his wife and mother. The latter was the victim of his atrocious crime; the motive of it being to get possession of the sum of five hundred pounds, which was this woman’s property. Linkworth, as came out at the trial, was in debt to the extent of a hundred pounds at the time, and during his wife’s absence from home on a visit to relations, he strangled his mother, and during the night buried the body in the small back-garden of his house. On his wife’s return, he had a sufficiently plausible tale to account for the elder Mrs. Linkworth’s disappearance, for there had been constant jarrings and bickerings between him and his mother for the last year or two, and she had more than once threatened to withdraw herself and the eight shillings a week which she contributed to household expenses, and purchase an annuity with her money. It was true, also, that during the younger Mrs. Linkworth’s absence from home, mother and son had had a violent quarrel arising originally from some trivial point in household management, and that in consequence of this, she had actually drawn her money out of the bank, intending to leave Sheffield next day and settle in London, where she had friends. That evening she told him this, and during the night he killed her.

His next step, before his wife’s return, was logical and sound. He packed up all his mother’s possessions and took them to the station, from which he saw them despatched to town by passenger train, and in the evening he asked several friends in to supper, and told them of his mother’s departure. He did not (logically also, and in accordance with what they probably already knew) feign regret, but said that he and she had never got on well together, and that the cause of peace and quietness was furthered by her going. He told the same story to his wife on her return, identical in every detail, adding, however, that the quarrel had been a violent one, and that his mother had not even left him her address. This again was wisely thought of: it would prevent his wife from writing to her. She appeared to accept his story completely: indeed there was nothing strange or suspicious about it.

For a while he behaved with the composure and astuteness which most criminals possess up to a certain point, the lack of which, after that, is generally the cause of their detection. He did not, for instance, immediately pay off his debts, but took into his house a young man as lodger, who occupied his mother’s room, and he dismissed the assistant in his shop, and did the entire serving himself. This gave the impression of economy, and at the same time he openly spoke of the great improvement in his trade, and not till a month had passed did he cash any of the bank-notes which he had found in a locked drawer in his mother’s room. Then he changed two notes of fifty pounds and paid off his creditors.

At that point his astuteness and composure failed him. He opened a deposit account at a local bank with four more fifty-pound notes, instead of being patient, and increasing his balance at the savings bank pound by pound, and he got uneasy about that which he had buried deep enough for security in the back-garden. Thinking to render himself safer in this regard, he ordered a cartload of slag and stone fragments, and with the help of his lodger employed the summer evenings when work was over in building a sort of rockery over the spot. Then came the chance circumstance which really set match to this dangerous train. There was a fire in the lost luggage office at King’s Cross Station (from which he ought to have claimed his mother’s property) and one of the two boxes was partially burned. The company was liable for compensation, and his mother’s name on her linen, and a letter with the Sheffield address on it, led to the arrival of a purely official and formal notice, stating that the company were prepared to consider claims. It was directed to Mrs. Linkworth’s and Charles Linkworth’s wife received and read it.

It seemed a sufficiently harmless document, but it was endorsed with his death-warrant. For he could give no explanation at all of the fact of the boxes still lying at King’s Cross Station, beyond suggesting that some accident had happened to his mother. Clearly he had to put the matter in the hands of the police, with a view to tracing her movements, and if it proved that she was dead, claiming her property, which she had already drawn out of the bank. Such at least was the course urged on him by his wife and lodger, in whose presence the communication from the railway officials was read out, and it was impossible to refuse to take it. Then the silent, uncreaking machinery of justice, characteristic of England, began to move forward. Quiet men lounged about Smith Street, visited banks, observed the supposed increase in trade, and from a house near by looked into the garden where ferns were already flourishing on the rockery. Then came the arrest and the trial, which did not last very long, and on a certain Saturday night the verdict. Smart women in large hats had made the court bright with colour, and in all the crowd there was not one who felt any sympathy with the young athletic-looking man who was condemned. Many of the audience were elderly and respectable mothers, and the crime had been an outrage on motherhood, and they listened to the unfolding of the flawless evidence with strong approval. They thrilled a little when the judge put on the awful and ludicrous little black cap, and spoke the sentence appointed by God.

Linkworth went to pay the penalty for the atrocious deed, which no one who had heard the evidence could possibly doubt that he had done with the same indifference as had marked his entire demeanour since he knew his appeal had failed. The prison chaplain who had attended him had done his utmost to get him to confess, but his efforts had been quite ineffectual, and to the last he asserted, though without protestation, his innocence. On a bright September morning, when the sun shone warm on the terrible little procession that crossed the prison yard to the shed where was erected the apparatus of death, justice was done, and Dr. Teesdale was satisfied that life was immediately extinct. He had been present on the scaffold, had watched the bolt drawn, and the hooded and pinioned figure drop into the pit. He had heard the chunk and creak of the rope as the sudden weight came on to it, and looking down he had seen the queer twitchings of the hanged body. They had lasted but a second for the execution had been perfectly satisfactory.

An hour later he made the post-mortem examination and found that his view had been correct: the vertebrae of the spine had been broken at the neck, and death must have been absolutely instantaneous. It was hardly necessary even to make that little piece of dissection that proved this, but for the sake of form he did so. And at that moment he had a very curious and vivid mental impression that the spirit of the dead man was close beside him, as if it still dwelt in the broken habitation of its body. But there was no question at all that the body was dead: it had been dead an hour. Then followed another little circumstance that at the first seemed insignificant though curious also. One of the warders entered, and asked if the rope which had been used an hour ago, and was the hangman’s perquisite, had by mistake been brought into the mortuary with the body. But there was no trace of it, and it seemed to have vanished altogether, though it a singular thing to be lost: it was not here; it was not on the scaffold. And though the disappearance was of no particular moment it was quite inexplicable.

Dr. Teesdale was a bachelor and a man of independent means, and lived in a tall-windowed and commodious house in Bedford Square, where a plain cook of surpassing excellence looked after his food, and her husband his person. There was no need for him to practise a profession at all, and he performed his work at the prison for the sake of the study of the minds of criminals.

Most crime—the transgression, that is, of the rule of conduct which the human race has framed for the sake of its own preservation—he held to be either the result of some abnormality, of the brain or of starvation. Crimes of theft, for instance, he would by no means refer to one head; often it is true they were the result of actual want, but more often dictated by some obscure disease of the brain. In marked cases it was labelled as kleptomania, but he was convinced there were many others which did not fall directly under the dictation of physical need. More especially was this the case where the crime in question involved also some deed of violence, and he mentally placed underneath this heading, as he went home that evening, the criminal at whose last moments he had been present that morning. The crime had been abominable, the need of money not so very pressing, and the very abomination and unnaturalness of the murder inclined him to consider the murderer as lunatic rather than criminal. He had been, as far as was known, a man of quiet and kindly disposition, a good husband, a sociable neighbour. And then he had committed a crime, just one, which put him outside all pales. So monstrous a deed, whether perpetrated by a sane man or a mad one, was intolerable; there was no use for the doer of it on this planet at all. But somehow the doctor felt that he would have been more at one with the execution of justice, if the dead man had confessed. It was morally certain that he was guilty, but he wished that when there was no longer any hope for him he had endorsed the verdict himself.

He dined alone that evening, and after dinner sat in his study which adjoined the dining-room, and feeling disinclined to read, sat in his great red chair opposite the fireplace, and let his mind graze where it would. At once almost, it went back to the curious sensation he had experienced that morning, of feeling that the spirit of Linkworth was present in the mortuary, though life had been extinct for an hour. It was not the first time, especially in cases of sudden death, that he had felt a similar conviction, though perhaps it had never been quite so unmistakable as it had been to-day. Yet the feeling, to his mind, was quite probably formed on a natural and psychical truth.

The spirit—it may be remarked that he was a believer in the doctrine of future life, and the non-extinction of the soul with the death of the body—was very likely unable or unwilling to quit at once and altogether the earthly habitation, very likely it lingered there, earth-bound, for a while.

In his leisure hours Dr. Teesdale was a considerable student of the occult, for like most advanced and proficient physicians, he clearly recognised how narrow was the boundary of separation between soul and body, how tremendous the influence of the intangible was over material things, and it presented no difficulty to his mind that a disembodied spirit should be able to communicate directly with those who still were bounded by the finite and material.

His meditations, which were beginning to group themselves into definite sequence, were interrupted at this moment. On his desk near at hand stood his telephone, and the bell rang, not with its usual metallic insistence, but very faintly, as if the current was weak, or the mechanism impaired. However, it certainly was ringing, and he got up and took the combined ear and mouth-piece off its hook.

“Yes, yes,” he said, “who is it?”

There was a whisper in reply almost inaudible, and quite unintelligible.

“I can’t hear you,” he said.

Again the whisper sounded, but with no greater distinctness. Then it ceased altogether.

He stood there, for some half minute or so, waiting for it to be renewed, but beyond the usual chuckling and croaking, which showed, however, that he was in communication with some other instrument, there was silence. Then he replaced the receiver, rang up the Exchange, and gave his number.

“Can you tell me what number rang me up just now?” he asked.

There was a short pause, then it was given him. It was the number of the prison, where he was doctor.

“Put me on to it, please,” he said.

This was done.

“You rang me up just now,” he said down the tube. “Yes; I am Doctor Teesdale. What is it? I could not hear what you said.”

The voice came back quite clear and intelligible.

“Some mistake, sir,” it said. “We haven’t rung you up.”

“But the Exchange tells me you did, three minutes ago.”

“Mistake at the Exchange, sir,” said the voice.

“Very odd. Well, good-night. Warder Draycott, isn’t it?”

“Yes, sir; good-night, sir.”

Dr. Teesdale went back to his big arm-chair, still less inclined to read. He let his thoughts wander on for a while, without giving them definite direction, but ever and again his mind kept coming back to that strange little incident of the telephone. Often and often he had been rung up by some mistake, often and often he had been put on to the wrong number by the Exchange, but there was something in this very subdued ringing of the telephone bell, and the unintelligible whisperings at the other end that suggested a very curious train of reflection to his mind, and soon he found himself pacing up and down his room, with his thoughts eagerly feeding on a most unusual pasture.

“But it’s impossible,” he said, aloud.

He went down as usual to the prison next morning, and once again he was strangely beset with the feeling that there was some unseen presence there. He had before now had some odd psychical experiences, and knew that he was a “sensitive”—one, that is, who is capable, under certain circumstances, of receiving supernormal impressions, and of having glimpses of the unseen world that lies about us. And this morning the presence of which he was conscious was that of the man who had been executed yesterday morning. It was local, and he felt it most strongly in the little prison yard, and as he passed the door of the condemned cell. So strong was it there that he would not have been surprised if the figure of the man had been visible to him, and as he passed through the door at the end of the passage, he turned round, actually expecting to see it. All the time, too, he was aware of a profound horror at his heart; this unseen presence strangely disturbed him. And the poor soul, he felt, wanted something done for it. Not for a moment did he doubt that this impression of his was objective, it was no imaginative phantom of his own invention that made itself so real. The spirit of Linkworth was there.

He passed into the infirmary, and for a couple of hours busied himself with his work. But all the time he was aware that the same invisible presence was near him, though its force was manifestly less here than in those places which had been more intimately associated with the man. Finally, before he left, in order to test his theory he looked into the execution shed. But next moment with a face suddenly stricken pale, he came out again, closing the door hastily. At the top of the steps stood a figure hooded and pinioned, but hazy of outline and only faintly visible.

But it was visible, there was no mistake about it.

Dr. Teesdale was a man of good nerve, and he recovered himself almost immediately, ashamed of his temporary panic. The terror that had blanched his face was chiefly the effect of startled nerves, not of terrified heart, and yet deeply interested as he was in psychical phenomena, he could not command himself sufficiently to go back there. Or rather he commanded himself, but his muscles refused to act on the message. If this poor earth-bound spirit had any communication to make to him, he certainly much preferred that it should be made at a distance. As far as he could understand, its range was circumscribed. It haunted the prison yard, the condemned cell, the execution shed, it was more faintly felt in the infirmary. Then a further point suggested itself to his mind, and he went back to his room and sent for Warder Draycott, who had answered him on the telephone last night.

“You are quite sure,” he asked, “that nobody rang me up last night, just before I rang you up?”

There was a certain hesitation in the man’s manner which the doctor noticed.

“I don’t see how it could be possible, sir,” he said. “I had been sitting close by the telephone for half an hour before, and again before that. I must have seen him, if anyone had been to the instrument.”

“And you saw no one?” said the doctor with a slight emphasis.

The man became more markedly ill at ease.

“No, sir, I saw no one,” he said, with the same emphasis.

Dr. Teesdale looked away from him.

“But you had perhaps the impression that there was some one there?” he asked, carelessly, as if it was a point of no interest.

Clearly Warder Draycott had something on his mind, which he found it hard to speak of.

“Well, sir, if you put it like that,” he began. “But you would tell me I was half asleep, or had eaten something that disagreed with me at my supper.”

The doctor dropped his careless manner.

“I should do nothing of the kind,” he said, “any more than you would tell me that I had dropped asleep last night, when I heard my telephone bell ring. Mind you, Draycott, it did not ring as usual, I could only just hear it ringing, though it was close to me. And I could only hear a whisper when I put my ear to it. But when you spoke I heard you quite distinctly. Now I believe there was something—somebody—at this end of the telephone. You were here, and though you saw no one, you, too, felt there was someone there.”

The man nodded.

“I’m not a nervous man, sir,” he said, “and I don’t deal in fancies. But there was something there. It was hovering about the instrument, and it wasn’t the wind, because there wasn’t a breath of wind stirring, and the night was warm. And I shut the window to make certain. But it went about the room, sir, for an hour or more. It rustled the leaves of the telephone book, and it ruffled my hair when it came close to me. And it was bitter cold, sir.”

The doctor looked him straight in the face.

“Did it remind you of what had been done yesterday morning?” he asked suddenly.

Again the man hesitated.

“Yes, sir,” he said at length. “Convict Charles Linkworth.”

Dr. Teesdale nodded reassuringly.

“That’s it,” he said. “Now, are you on duty to-night?”

“Yes, sir, I wish I wasn’t.”

“I know how you feel, I have felt exactly the same myself. Now whatever this is, it seems to want to communicate with me. By the way, did you have any disturbance in the prison last night?”

“Yes, sir, there was half a dozen men who had the nightmare. Yelling and screaming they were, and quiet men too, usually. It happens sometimes the night after an execution. I’ve known it before, though nothing like what it was last night.”

“I see. Now, if this—this thing you can’t see wants to get at the telephone again to-night, give it every chance. It will probably come about the same time. I can’t tell you why, but that usually happens. So unless you must, don’t be in this room where the telephone is, just for an hour to give it plenty of time between half-past nine and half-past ten. I will be ready for it at the other end. Supposing I am rung up, I will, when it has finished, ring you up to make sure that I was not being called in—in the usual way.”

“And there is nothing to be afraid of, sir?” asked the man.

Dr. Teesdale remembered his own moment of terror this morning, but he spoke quite sincerely.

“I am sure there is nothing to be afraid of,” he said, reassuringly.

Dr. Teesdale had a dinner engagement that night, which he broke, and was sitting alone in his study by half past-nine. In the present state of human ignorance as to the law which governs the movements of spirits severed from the body, he could not tell the warder why it was that their visits are so often periodic, timed to punctuality according to our scheme of hours, but in scenes of tabulated instances of the appearance of revenants, especially if the soul was in sore need of help, as might be the case here, he found that they came at the same hour of day or night. As a rule, too, their power of making themselves seen or heard or felt grew greater for some little while after death, subsequently growing weaker as they became less earth-bound, or often after that ceasing altogether, and he was prepared to-night for a less indistinct impression. The spirit apparently for the early hours of its disembodiment is weak, like a moth newly broken out from its chrysalis—and then suddenly the telephone bell rang, not so faintly as the night before, but still not with its ordinary imperative tone.

Dr. Teesdale instantly got up, put the receiver to his ear. And what he heard was heartbroken sobbing, strong spasms that seemed to tear the weeper.

He waited for a little before speaking, himself cold with some nameless fear, and yet profoundly moved to help, if he was able.

“Yes, yes,” he said at length, hearing his own voice tremble. “I am Dr. Teesdale. What can I do for you? And who are you?” he added, though he felt that it was a needless question.

Slowly the sobbing died down, the whispers took its place, still broken by crying.

“I want to tell, sir—I want to tell—I must tell.”

“Yes, tell me, what is it?” said the doctor.

“No, not you—another gentleman, who used to come to see me. Will you speak to him what I say to you?—I can’t make him hear me or see me.”

“Who are you?” asked Dr. Teesdale suddenly.

“Charles Linkworth. I thought you knew. I am very miserable. I can’t leave the prison—and it is cold. Will you send for the other gentleman?”

“Do you mean the chaplain?” asked Dr. Teesdale.

“Yes, the chaplain. He read the service when I went across the yard yesterday. I shan’t be so miserable when I have told.”

The doctor hesitated a moment. This was a strange story that he would have to tell Mr. Dawkins, the prison chaplain, that at the other end of the telephone was the spirit of the man executed yesterday. And yet he soberly believed that it was so, that this unhappy spirit was in misery and wanted to “tell.” There was no need to ask what he wanted to tell.

“Yes, I will ask him to come here,” he said at length.

“Thank you, sir, a thousand times. You will make him come, won’t you?”

The voice was growing fainter.

“It must be to-morrow night,” it said. “I can’t speak longer now. I have to go to see—oh, my God, my God.”

The sobs broke out afresh, sounding fainter and fainter. But it was in a frenzy of terrified interest that Dr. Teesdale spoke.

“To see what?” he cried. “Tell me what you are doing, what is happening to you?”

“I can’t tell you; I mayn’t tell you,” said the voice very faint. “That is part—” and it died away altogether.

Dr. Teesdale waited a little, but there was no further sound of any kind, except the chuckling and croaking of the instrument. He put the receiver on to its hook again, and then became aware for the first time that his forehead was streaming with some cold dew of horror. His ears sang; his heart beat very quick and faint, and he sat down to recover himself. Once or twice he asked himself if it was possible that some terrible joke was being played on him, but he knew that could not be so; he felt perfectly sure that he had been speaking with a soul in torment of contrition for the terrible and irremediable act it had committed. It was no delusion of his senses, either; here in this comfortable room of his in Bedford Square, with London cheerfully roaring round him, he had spoken with the spirit of Charles Linkworth.

But he had no time (nor indeed inclination, for somehow his soul sat shuddering within him) to indulge in meditation. First of all he rang up the prison.

“Warder Draycott?” he asked.

There was a perceptible tremor in the man’s voice as he answered.

“Yes, sir. Is it Dr. Teesdale?”

“Yes. Has anything happened here with you?”

Twice it seemed that the man tried to speak and could not. At the third attempt the words came “Yes, sir. He has been here. I saw him go into the room where the telephone is.”

“Ah! Did you speak to him?”

“No, sir: I sweated and prayed. And there’s half a dozen men as have been screaming in their sleep to-night. But it’s quiet again now. I think he has gone into the execution shed.”

“Yes. Well, I think there will be no more disturbance now. By the way, please give me Mr. Dawkins’s home address.”

This was given him, and Dr. Teesdale proceeded to write to the chaplain, asking him to dine with him on the following night. But suddenly he found that he could not write at his accustomed desk, with the telephone standing close to him, and he went upstairs to the drawing-room which he seldom used, except when he entertained his friends. There he recaptured the serenity of his nerves, and could control his hand. The note simply asked Mr. Dawkins to dine with him next night, when he wished to tell him a very strange history and ask his help. “Even if you have any other engagement,” he concluded, “I seriously request you to give it up. To-night, I did the same.

“I should bitterly have regretted it if I had not.”

Next night accordingly, the two sat at their dinner in the doctor’s dining-room, and when they were left to their cigarettes and coffee the doctor spoke.

“You must not think me mad, my dear Dawkins,” he said, “when you hear what I have got to tell you.”

Mr. Dawkins laughed.

“I will certainly promise not to do that,” he said.

“Good. Last night and the night before, a little later in the evening than this, I spoke through the telephone with the spirit of the man we saw executed two days ago. Charles Linkworth.”

The chaplain did not laugh. He pushed back his chair, looking annoyed.

“Teesdale,” he said, “is it to tell me this—I don’t want to be rude—but this bogey-tale that you have brought me here this evening?”

“Yes. You have not heard half of it. He asked me last night to get hold of you. He wants to tell you something. We can guess, I think, what it is.”

Dawkins got up.

“Please let me hear no more of it,” he said. “The dead do not return. In what state or under what condition they exist has not been revealed to us. But they have done with all material things.”

“But I must tell you more,” said the doctor. “Two nights ago I was rung up, but very faintly, and could only hear whispers. I instantly inquired where the call came from and was told it came from the prison. I rang up the prison, and Warder Draycott told me that nobody had rung me up. He, too, was conscious of a presence.”

“I think that man drinks,” said Dawkins, sharply.

The doctor paused a moment.

“My dear fellow, you should not say that sort of thing,” he said. “He is one of the steadiest men we have got. And if he drinks, why not I also?”

The chaplain sat down again.

“You must forgive me,” he said, “but I can’t go into this. These are dangerous matters to meddle with. Besides, how do you know it is not a hoax?”

“Played by whom?” asked the doctor. “Hark!”

The telephone bell suddenly rang. It was clearly audible to the doctor.

“Don’t you hear it?” he said.

“Hear what?”

“The telephone bell ringing.”

“I hear no bell,” said the chaplain, rather angrily. “There is no bell ringing.”

The doctor did not answer, but went through into his study, and turned on the lights. Then he took the receiver and mouthpiece off its hook.

“Yes?” he said, in a voice that trembled. “Who is it? Yes: Mr. Dawkins is here. I will try and get him to speak to you.” He went back into the other room.

“Dawkins,” he said, “there is a soul in agony. I pray you to listen. For God’s sake come and listen.”

The chaplain hesitated a moment.

“As you will,” he said.

He took up the receiver and put it to his ear.

“I am Mr. Dawkins,” he said.

He waited.

“I can hear nothing whatever,” he said at length. “Ah, there was something there. The faintest whisper.”

“Ah, try to hear, try to hear!” said the doctor.

Again the chaplain listened. Suddenly he laid the instrument down, frowning.

“Something—somebody said, ‘I killed her, I confess it. I want to be forgiven.’ It’s a hoax, my dear Teesdale. Somebody knowing your spiritualistic leanings is playing a very grim joke on you. I can’t believe it.”

Dr. Teesdale took up the receiver.

“I am Dr. Teesdale,” he said. “Can you give Mr. Dawkins some sign that it is you?”

Then he laid it down again.

“He says he thinks he can,” he said. “We must wait.”

The evening was again very warm, and the window into the paved yard at the back of the house was open. For five minutes or so the two men stood in silence, waiting, and nothing happened. Then the chaplain spoke.

“I think that is sufficiently conclusive,” he said.

Even as he spoke a very cold draught of air suddenly blew into the room, making the papers on the desk rustle. Dr. Teesdale went to the window and closed it.

“Did you feel that?” he asked.

“Yes, a breath of air. Chilly.”

Once again in the closed room it stirred again.

“And did you feel that?” asked the doctor.

The chaplain nodded. He felt his heart hammering in his throat suddenly.

“Defend us from all peril and danger of this coming night,” he exclaimed.

“Something is coming!” said the doctor.

As he spoke it came. In the centre of the room not three yards away from them stood the figure of a man with his head bent over on to his shoulder, so that the face was not visible. Then he took his head in both his hands and raised it like a weight, and looked them in the face. The eyes and tongue protruded, a livid mark was round the neck. Then there came a sharp rattle on the boards of the floor, and the figure was no longer there. But on the floor there lay a new rope.

For a long while neither spoke. The sweat poured off the doctor’s face, and the chaplain’s white lips whispered prayers. Then by a huge effort the doctor pulled himself together. He pointed at the rope.

“It has been missing since the execution,” he said.

Then again the telephone bell rang. This time the chaplain needed no prompting. He went to it at once and the ringing ceased. For a while he listened in silence.

“Charles Linkworth,” he said at length, “in the sight of God, in whose presence you stand, are you truly sorry for your sin?”

Some answer inaudible to the doctor came, and the chaplain closed his eyes. And Dr. Teesdale knelt as he heard the words of the Absolution.

At the close there was silence again.

“I can hear nothing more,” said the chaplain, replacing the receiver.

Presently the doctor’s man-servant came in with the tray of spirits and syphon. Dr. Teesdale pointed without looking to where the apparition had been.

“Take the rope that is there and burn it, Parker,” he said.

There was a moment’s silence.

“There is no rope, sir,” said Parker.

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)