Public Domain Text: Expiation by E. F. Benson

Expiation is a short story by E. F. Benson. Like a number of his stories, it was first published in Hutchinson’s Magazine (November 1923).

Five years later, Expiation got a second outing when Benson included it in his short story anthology, Spook Stories. Since then, the story has been republished many more times but mostly in E. F. Benson short story collections.

Expiation follows the events that happen when two friends rent a holiday home near the Cornish coast. The house is lovely, as is the garden but both men soon become aware things at their Cornish haven are not quite right. They hear things. Then they see things and finally learn the dark secret of their almost idyllic holiday retreat.

About E. F. Benson

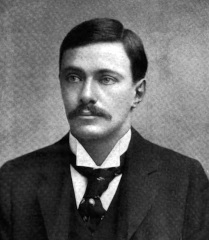

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

Expiation

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

Philip Stuart and I, unattached and middle-aged persons, had for the last four or five years been accustomed to spend a month or six weeks together in the summer, taking a furnished house in some part of the country, which, by an absence of attractive pursuits, was not likely to be over-run by gregarious holiday-makers. When, as the season for getting out of London draws near, and we scan the advertisement columns which set forth the charms and the cheapness of residences to be let for August, and see the mention of tennis-clubs and esplanades and admirable golf-links within a stone’s throw of the proposed front door, our offended and disgusted eyes instantly wander to the next item.

For the point of a holiday, according to our private heresy, is not to be entertained and occupied and jostled by glad crowds, but to have nothing to do, and no temptation which might lead to any unseasonable activity. London has held employments and diversion enough; we want to be without both. But vicinity to the sea is desirable, because it is easier to do nothing by the sea than anywhere else, and because bathing and basking on the shore cannot be considered an employment but only an apotheosis of loafing. A garden also is a requisite, for that tranquillises any fidgety notion of going for a walk.

In pursuance of this sensible policy we had this year taken a house on the south coast of Cornwall, for a relaxing climate conduces to laziness. It was too far off for us to make any personal inspection of it, but a perusal of the modestly-worded advertisement carried conviction. It was close to the sea; the village Polwithy, outside which it was situated, was remote and, as far as we knew, unknown; it had a garden, and there was attached to it a cook-housekeeper who made for simplification. No mention of golf-links or attractive resorts in the neighbourhood defiled the bald and terse specification, and though there was a tennis-court in the garden, there was no clause that bound the tenants to use it. The owner was a Mrs. Hearne, who had been living abroad, and our business was transacted with a house-agent in Falmouth.

To make our household complete, Philip sent down a parlourmaid, and I a housemaid, and after leaving them a day in which to settle in, we followed. There was a six-mile drive from the station across high uplands, and at the end a long steady descent into a narrow valley, cloven between the hills, that grew ever more luxuriant in verdure as we descended. Great trees of fuchsia spread up to the eaves of the thatched cottages which stood by the wayside, and a stream, embowered in green thickets, ran babbling through the centre of it. Presently we came to the village, no more than a dozen houses, built of the grey stone of the district, and on a shelf just above it a tiny church with parsonage adjoining. High above us now flamed the gorse-clad slopes of the hills on each side, and now the valley opened out at its lower end, and the still warm air was spiced and renovated by the breeze that drew up it from the sea. Then round a sharp angle of the road we came alongside a stretch of brick wall, and stopped at an iron gate above which flowed a riot of rambler rose.

It seemed hardly credible that it was this of which that terse and laconic advertisement had spoken. I had pictured something of villa-ish kind, yellow bricked perhaps, with a roof of purplish slate, a sitting-room one side of the entrance, a dining-room the other; with a tiled hall and a pitch-pine staircase, and instead, here was this little gem of an early Georgian manor house, mellow and gracious, with mullioned windows and a roof of stone slabs. In front of it was a paved terrace, below which blossomed a herbaceous border, tangled and tropical, with no inch of earth visible through its luxuriance. Inside, too, was fulfilment of this fair exterior: a broad-balustered staircase led up from the odiously-entitled “lounge hall,” which I had pictured as a medley of Benares ware and saddle-bagged sofas, but which proved to be cool, broad and panelled, with a door opposite that through which we entered, leading on to the further area of garden at the back. There was the advertised but innocuous tennis court, bordered on the length of its far side by a steep grass bank, along which was planted a row of limes, once pollarded, but now allowed to develop at will. Thick boughs, some fourteen or fifteen feet from the ground, interlaced with each other, forming an arcaded row; above them, where Nature had been permitted to go her own way, the trees broke into feathered and honey-scented branches. Beyond lay a small orchard climbing upwards, above that the hillside rose more steeply, in broad spaces of short-cropped turf and ablaze with gorse, the Cornish gorze that flowers all the year round, and spreads its sunshine from January to December.

There was time for a stroll through this perfect little domain before dinner, and for a short interview with the housekeeper, a quiet capable-looking woman, slightly aloof, as is the habit of her race, from strangers and foreigners, for so the Cornish account the English, but who proved herself at the repast that followed to be as capable as she appeared. The evening closed in hot and still, and after dinner we took chairs out on to the terrace in front of the house.

“Far the best place we’ve struck yet,” observed Philip. “Why did no one say Polwithy before?”

“Because nobody had ever heard of it, luckily,” said I.

“Well, I’m a Polwithian. At least I am in spirit. But how aware Mrs.—Mrs. Criddle made me feel that I wasn’t really.”

Philip’s profession, a doctor of obscure nervous diseases, has made him preternaturally acute in the diagnosis of what other people feel, and for some reason, quite undefined, I wanted to know what exactly he meant by this. I was in sympathy with his feeling, but I could not analyse it.

“Describe your symptoms,” I said.

“I have. When she came up and talked to us, and hoped we should be comfortable, and told us that she would do her best, she was just gossiping. Probably it was perfectly true gossip. But it wasn’t she. However, as that’s all that matters, there’s no reason why we should probe further.”

“Which means that you have,” I said.

“No; it means that I tried to and couldn’t. She gave me an extraordinary sense of her being aware of something, which we knew nothing of; of being on a plane which we couldn’t imagine. I constantly meet such people; they aren’t very rare. I don’t mean that there’s anything the least uncanny about them, or that they know things that are uncanny. They are simply aloof, as hard to understand as your dog or your cat. She would find us equally aloof if she succeeded in analysing her sensations about us, but like a sensible woman she probably feels not the smallest interest in us. She is there to bake and to boil, and we are there to eat her bakings and appreciate her boilings.”

The subject dropped, and we sat on in the dusk that was rapidly deepening into night. The door into the hall was open at our backs, and a panel of light from the lamps within was cast out on to the terrace. Wandering moths, invisible in the darkness, suddenly became manifest as they fluttered into this illumination, and vanished again as they passed out of it. One moment they were there, living things with life and motion of their own, the next they had quite disappeared. How inexplicable that would be, I thought, if one did not know from long familiarity, that light of the appropriate sort and strength is needed to make material objects visible.

Philip must have been following precisely the same train of thought, for his voice broke in, carrying it a little further.

“Look at that moth,” he said, “and even while you look it has gone like a ghost, even as like a ghost it appeared. Light made it visible. And there are other sorts of light, interior psychical light which similarly makes visible the beings which people the darkness of our blindness.”

Just as he spoke I thought for the moment that I heard the tingle of a telephone bell. It sounded very faintly, and I could not have sworn that I had actually heard it. At the most it gave one staccato little summons and was silent again.

“Is there a telephone in the house?” I asked “I haven’t noticed one.”

“Yes, by the door into the back garden,” said he. “Do you want to telephone?”

“No, but I thought I heard it ring. Didn’t you?”

He shook his head; then smiled.

“Ah, that was it,” he said.

Certainly now there was the clink of glass, rather bell-like, as the parlourmaid came out of the dining-room with a tray of syphon and decanter, and my reasonable mind was quite content to accept this very probable explanation. But behind that, quite unreasonably, some little obstinate denizen of my consciousness rejected it. It told me that what I had heard was like the moth that came out of darkness and went on into darkness again.

My room was at the back of the house, overlooking the lawn tennis-court, and presently I went up to bed. The moon had risen, and the lawn lay in bright illumination bordered by a strip of dark shadow below the pollarded limes. Somewhere along the hillside an owl was foraging, softly hooting, and presently it swept whitely across the lawn. No sound is so intensely rural, yet none, to my mind, so suggests a signal. But it seemed to signal nothing, and, tired with the long hot journey, and soothed by the deep tranquillity of the place, I was soon asleep. But often during the night I woke, though never to more than a dozing dreamy consciousness of where I was, and each time I had the notion that some slight noise had roused me, and each time I found myself listening to hear whether the tingle of a telephone bell was the cause of my disturbance. There came no repetition of it, and again I slept, and again I woke with drowsy attention for the sound which I felt I expected, but never heard.

Daylight banished these imaginations, but though I must have slept many hours all told, for these wakings had been only brief and partial, I was aware of a certain weariness, as if though my bodily senses had been rested, some part of me had been wakeful and watching all night. This was fanciful enough to disregard, and certainly during the day I forgot it altogether. Soon after breakfast we went down to the sea, and a short ramble along a shingly shore brought us to a sandy cove framed in promontories of rock that went down into deep water. The most fastidious connoisseur in bathing could have pictured no more ideal scene for his operations, for with hot sand to bask on and rocks to plunge from, and a limpid ocean and a cloudless sky, there was indeed no lacuna in perfection. All morning we loafed here, swimming and sunning ourselves, and for the afternoon there was the shade of the garden, and a stroll later on up through the orchard and to the gorse-clad hillside. We came back through the churchyard, looked into the church, and coming out, Philip pointed to a tombstone which from its newness among its dusky and moss-grown companions, easily struck the eye. It recorded without pious or scriptural reflection the date of the birth and death of George Hearne; the latter event had taken place close on two years ago, and we were within a week of the exact anniversary. Other tombstones near were monuments to those of the same name, and dated back for a couple of centuries and more.

“Local family,” said I, and strolling on we came to our own gate in the long brick wall. It was opened from inside just as we arrived at it, and there came out a brisk middle-aged man in clergyman’s dress, obviously our vicar.

He very civilly introduced himself.

“I heard that Mrs. Hearne’s house had been taken, and that the tenants had come,” he said, “and I ventured to leave my card.”

We performed our part of the ceremony, and in answer to his inquiry professed our satisfaction with our quarters and our neighbourhood.

“That is good news,” said Mr. Stephens, “I hope you will continue to enjoy your holiday. I am Cornish myself, and like all natives think there is no place like Cornwall!”

Philip pointed with his stick towards the churchyard. “We noticed that the Hearnes are people of the place,” he said. Quite suddenly I found myself understanding what he had meant by the aloofness of the race. Something between reserve and suspicion came into Mr. Stephens’s face.

“Yes, yes, an old family here,” he said, “and large landowners. But now some remote cousin—The house, however, belongs to Mrs. Hearne for life.”

He stopped, and by that reticence confirmed the impression he had made. In consequence, for there is something in the breast of the most incurious, which, when treated with reserve becomes inquisitive, Philip proceeded to ask a direct question.

“Then I take it that the George Hearne who, as I have just seen, died two years ago, was the husband of Mrs. Hearne, from whom we took the house?”

“Yes, he was buried in the churchyard,” said Mr. Stephens quickly. Then, for no reason at all, he added:

“Naturally he was buried in the churchyard here.”

Now my impression at that moment was that Mr. Stephens had said something he did not mean to say, and had corrected it by saying the same thing again. He went on his way, back to the vicarage, with an amiably expressed desire to do anything that was in his power for us, in the way of local information, and we went in through the gate. The post had just arrived; there was the London morning paper and a letter for Philip which cost him two perusals before he folded it up and put it into his pocket. But he made no comment, and presently, as dinner-time was near, I went up to my room. Here in this deep valley with the great westerly hill towering above us, it was already dark, and the lawn lay beneath a twilight as of deep clear water. Quite idly as I brushed my hair in front of the glass on the table in the window, of which the blinds were not yet drawn, I looked out, and saw that on the bank along which grew the pollarded limes, there was lying a ladder. It was just a shade odd that it should be there, but the oddity of it was quite accounted for by the supposition that the gardener had had business among the trees in the orchard, and had left it there, for the completion of his labours to-morrow. It was just as odd as that, and no odder, just worth a twitch of the imagination to account for it, but now completely accounted for.

I went downstairs, and passing Philip’s door heard the swish of ablutions which implied he was not quite ready, and in the most loafer-like manner I strolled round the corner of the house. The kitchen window which looked on to the tennis-court was open, and there was a good smell, I remember, coming from it. And still without thought of the ladder I had just seen, I mounted the slope of grass on to the tennis-court. Just across it was the bank where the pollarded limes grew, but there was no ladder lying there. Of course, the gardener must have remembered he had left it, and had returned to remove it exactly as I came downstairs. There was nothing singular about that, and I could not imagine why the thing interested me at all. But for some inexplicable reason I found myself saying: “But I did see the ladder just now.”

A bell—no telephone bell, but a welcome harbinger to a hungry man—sounded from inside the house, and I went back on to the terrace, just as Philip got downstairs. At dinner our speech rambled pleasantly over the accomplishments of to-day, and the prospects of to-morrow, and in due course we came to the consideration of Mr. Stephens. We settled that he was an aloof fellow, and then Philip said:

“I wonder why he hastened to tell us that George Hearne was buried in the churchyard, and then added that naturally he was!”

“It’s the natural place to be buried in,” said I.

“Quite. That’s just why it was hardly worth mentioning.”

I felt then, just momentarily, just vaguely, as if my mind was regarding stray pieces of a jig-saw puzzle. The fancied ringing of the telephone bell last night was one of them, this burial of George Hearne in the churchyard was another, and, even more inexplicably, the ladder I had seen under the trees was a third. Consciously I made nothing whatever out of them, and did not feel the least inclination to devote any ingenuity to so fortuitous a collection of pieces. Why shouldn’t I add, for that matter, our morning’s bathe, or the gorse on the hillside? But I had the sensation that, though my conscious brain was presently occupied with piquet, and was rapidly growing sleepy with the day of sun and sea, some sort of mole inside it was digging passages and connecting corridors below the soil.

Five eventless days succeeded, there were no more ladders, no more phantom telephone bells, and emphatically no more Mr. Stephens. Once or twice we met him in the village street and got from him the curtest salutation possible short of a direct cut. And yet somehow he seemed charged with information, so we lazily concluded, and he made for us a field of imaginative speculation. I remember that I constructed a highly fanciful romance, which postulated that George Hearne was not dead at all, but that Mr. Stephens had murdered some inconvenient blackmailer, whom he had buried with the rites of the church. Or—these romances always broke down under cross-examination from Philip—Mr. Stephens himself was George Hearne, who had fled from justice, and was supposed to have died. Or Mrs. Hearne was really George Hearne, and our admirable housekeeper was the real Mrs. Hearne. From such indications you may judge how the intoxication of the sun and the sea had overpowered us.

But there was one explanation of why Mr. Stephens had so hastily assured us that George Hearne was buried in the churchyard which never passed our lips. It was just because both Philip and I really believed it to be the true one, that we did not mention it. But just as if it was some fever or plague, we both knew that we were sickening with it. And then these fanciful romances stopped because we knew that the Real Thing was approaching. There had been faint glimpses of it before, like distant sheet-lightning; now the noise of it, authentic and audible, began to rumble.

There came a day of hot overclouded weather. We had bathed in the morning, and loafed in the afternoon, but Philip, after tea, had refused to come for our usual ramble, and I set out alone. That morning Mrs. Criddle had rather peremptorily told me that a room in the front of the house would prove much cooler for me, for it caught the sea-breeze, and though I objected that it would also catch the southerly sun, she had clearly made up her mind that I was to move from the bedroom overlooking the tennis-court and the pollarded limes, and there was no resisting so polite and yet determined a woman.

When I set out for my ramble after tea, the change had already been effected, and my brain nosed slowly about as I strolled sniffing for her reason, for no self-respecting brain could accept the one she gave. But in this hot drowsy air I entirely lacked nimbleness, and when I came back, the question had become a mere silly unanswerable riddle. I returned through the churchyard, and saw that in a couple of days we should arrive at the anniversary of George Hearne’s death.

Philip was not on the terrace in front of the house, and I went in at the door of the hall, expecting to find him there or in the back garden. Exactly as I entered my eye told me that there he was, a black silhouette against the glass door, at the end of the hall, which was open, and led through into the back garden. He did not turn round at the sound of my entry, but took a step or two in the direction of the far door, still framed in the oblong of it. I glanced at the table, where the post lay, found letters both for me and him, and looked up again. There was no one there.

He had hastened his steps, I supposed, but simultaneously I thought how odd it was that he had not taken his letters, if he was in the hall, and that he had not turned when I entered. However, I should find him just round the corner, and with his post and mine in my hand, I went towards the far door. As I approached it I felt a sudden cold stir of air, rather unaccountable, for the day was notably sultry, and went out. He was sitting at the far end of the tennis-court.

I went up to him with his letters.

“I thought I saw you just now in the hall,” I said. But I knew already that I had not seen him in the hall.

He looked up quickly.

“And have you only just come in?” he said.

“Yes; this moment. Why?”

“Because half an hour ago I went in to see if the post had come, and thought I saw you in the hall.”

“And what did I do?” I asked.

“You went out on to the terrace. But I didn’t find you there.”

There was a short pause as he opened his letters.

“Damned interesting,” he observed. “Because there’s someone here who isn’t you or me.”

“Anything else?” I asked.

He laughed, pointing at the row of trees.

“Yes, something too silly for words,” he said. “Just now I saw a piece of rope dangling from the big branch of that pollarded lime. I saw it quite distinctly. And then there wasn’t any rope there at all any more than there is now.”

Philosophers have argued about the strongest emotion known to man. Some say “love,” others “hate,” others “fear.” I am disposed to put “curiosity” on a level, at least, with these august sensations, just mere simple inquisitiveness. Certainly at the moment it rivalled fear in my mind, and there was a hint of that.

As he spoke the parlourmaid came out into the garden with a telegram in her hand. She gave it to Philip, who without a word scribbled a line on the reply-paid form inside it, and handed it back to her.

“Dreadful nuisance,” he said, “but there’s no help for it. A few days ago I got a letter which made me think I might have to go up to town, and this telegram makes it certain. There’s an operation possible on a patient of mine, which I hoped might have been avoided, but my locum tenens won’t take the responsibility of deciding whether it is necessary or not.”

He looked at his watch.

“I can catch the night train,” he said, “and I ought to be able to catch the night train back from town to-morrow. I shall be back, that is to say, the day after to-morrow in the morning. There’s no help for it. Ha! That telephone of yours will come in useful. I can get a taxi from Falmouth, and needn’t start till after dinner.”

He went into the house, and I heard him rattling and tapping at the telephone. Soon he called for Mrs. Criddle, and presently came out again.

“We’re not on the telephone service,” he said. “It was cut off a year ago, only they haven’t removed the apparatus. But I can get a trap in the village, Mrs. Criddle says, and she’s sent for it. If I start at once I shall easily be in time. Spicer’s packing a bag for me, and I’ll take a sandwich.”

He looked sharply towards the pollarded trees.

“Yes, just there,” he said. “I saw it plainly, and equally plainly I saw it not. And then there’s that telephone of yours.”

I told him now about the ladder I had seen below the tree where he saw the dangling rope.

“Interesting,” he said, “because it’s so silly and unexpected. It is really tragic that I should be called away just now, for it looks as if the—well, the matter were coming out of the darkness into a shaft of light. But I’ll be back, I hope, in thirty-six hours. Meantime do observe very carefully, and whatever you do, don’t make a theory. Darwin says somewhere that you can’t observe without a theory, but to make a theory is a great danger to an observer. It can’t help influencing your imagination; you tend to see or hear what falls in with your hypothesis. So just observe; be as mechanical as a phonograph and a photographic lens.”

Presently the dog-cart arrived and I went down to the gate with him. “Whatever it is that is coming through, is coming through in bits,” he said. “You heard a telephone; I saw a rope. We both saw a figure, but not simultaneously nor in the same place. I wish I didn’t have to go.”

I found myself sympathising strongly with this wish, when after dinner I found myself with a solitary evening in front of me, and the pledge to “observe” binding me. It was not mainly a scientific ardour that prompted this sympathy, and the desire for independent combination, but, quite emphatically, fear of what might be coming out of the huge darkness which lies on all sides of human experience. I could no longer fail to connect together the fancied telephone bell, the rope, and the ladder, for what made the chain between them was the figure that both Philip and I had seen. Already my mind was seething with conjectural theory, but I would not let the ferment of it ascend to my surface consciousness; my business was not to aid but rather stifle my imagination.

I occupied myself, therefore, with the ordinary devices of a solitary man, sitting on the terrace, and subsequently coming into the house, for a few spots of rain began to fall. But though nothing disturbed the outward tranquillity of the evening, the quietness administered no opiate to that seething mixture of fear and curiosity that obsessed me. I heard the servants creep bedwards up the back stairs and presently I followed them. Then, forgetting for the moment that my room had been changed, I tried the handle of the door of that which I had previously occupied. It was locked.

Now here, beyond doubt, was the sign of a human agency, and at once I was determined to get into the room. The key, I could see, was not in the door, which must therefore have been locked from outside. I therefore searched the usual cache for keys along the top of the door-frame, found it, and entered.

The room was quite empty, the blinds not drawn, and after looking round it, I walked across to the window. The moon was up, and though obscured behind clouds, gave sufficient light to enable me to see objects outside with tolerable distinctness. There was the row of pollarded limes, and then with a sudden intake of my breath I saw that a foot or two below one of the boughs there was suspended something whitish and oval which oscillated as it hung there. In the dimness I could see nothing more than that, but now conjecture crashed into my conscious brain. But even as I looked it was gone again; there was nothing there but deep shadow, the trees steadfast in the windless air. Simultaneously I knew that I was not alone in the room.

I turned swiftly about, but my eyes gave no endorsement of that conviction, and yet their evidence that there was no one here except myself failed to shake it. The presence, somewhere close to me, needed no such evidence; it was self-evident though invisible, and my forehead was streaming with the abject sweat of terror. Somehow I knew that the presence was that of the figure both Philip and I had seen that evening in the hall, and, credit it or not as you will, the fact that it was invisible made it infinitely the more terrible. I knew, too, that though my eyes were blind to it, it had got into closer touch with me; I knew more of its nature now, it had had tragic and awful commerce with evil and despair. Some sort of catalepsy was on me, while it thus obsessed me; presently, minutes afterwards or perhaps mere seconds, the grip and clutch of its power was relaxed, and with shaking knees I crossed the room and went out, and again locked the door. Even as I turned the key I smiled at the futility of that. With my emergence the terror completely passed; I went across the passage leading to my room, got into bed, and was soon asleep. But I had no more need to question myself as to why Mrs. Criddle made the change. Another guest, she knew, would come to occupy it as the season arrived when George Hearne died and was buried in the churchyard.

The night passed quietly and then succeeded a day hot and still and sultry beyond belief. The very sea had lost its coolness and vitality, and I came in from my swim tired and enervated instead of refreshed. No breeze stirred; the trees stood motionless as if cast in iron, and from horizon to horizon the sky was overlaid by an ever-thickening pall of cloud. The cohorts of storm and thunder were gathering in the stillness, and all day I felt that power, other than that of these natural forces, was being stored for some imminent manifestation.

As I came near to the house the horror deepened, and after dinner I had a mind to drop into the vicarage, according to Mr. Stephens’s general invitation, and get through an hour or two with other company than my own. But I delayed till it was past any reasonable time for such an informal visit, and ten o’clock still saw me on the terrace in front of the house. My nerves were all on edge, a stir or step in the house was sufficient to make me turn round in apprehension of seeing I knew not what, but presently it grew still. One lamp burned in the hall behind me; by it stood the candle which would light me to bed.

I went indoors soon after, meaning to go up to bed, then suddenly ashamed of this craven imbecility of mind, took the fancy to walk round the house for the purpose of convincing myself that all was tranquil and normal, and that my fear, that nameless indefinable load on my spirit, was but a product of this close and thundery night. The tension of the weather could not last much longer; soon the storm must break and the relief come, but it would be something to know that there was nothing more than that. Accordingly I went out again on to the terrace, traversed it and turned the corner of the house where lay the tennis lawn.

To-night the moon had not yet risen, and the darkness was such that I could barely distinguish the outline of the house, and that of the pollarded limes, but through the glass door that led from this side of the house into the hall, there shone the light of the lamp that stood there. All was absolutely quiet, and half reassured I traversed the lawn, and turned to go back. Just as I came opposite the lit door, I heard a sound very close at hand from under the deep shadow of the pollarded limes. It was as if some heavy object had fallen with a thump and rebound on the grass, and with it there came the noise of a creaking bough suddenly strained by some weight. Then interpretation came upon me with the unreasoning force of conviction, though in the blackness I could see nothing. But at the sound a horror such as I have never felt laid hold on me. It was scarcely physical at all, it came from some deep-seated region of the soul.

The heavens were rent, a stream of blinding light shot forth, and straight in front of my eyes a few yards from where I stood, I saw. The noise had been of a ladder thrown down on the grass, and from the bough of the pollarded lime, there was the figure of a man, white-faced against the blackness, oscillating and twisting on the rope that strangled him. Just that I saw before the stillness was torn to atoms by the roar of thunder, and as from a hose the rain descended. Once again, even before that first appalling riot had died, the clouds were shredded again by the lightning, and my eyes which had not moved from the place saw only the framed shadow of the trees, and their upper branches bowed by the pelting rain. All night the storm raged and bellowed making sleep impossible, and for an hour at least, between the peals of thunder, I heard the ringing of the telephone bell.

Next morning Philip returned, to whom I told exactly what is written here, but watch and observe as we might, neither of us, in the three further weeks which we spent at Polwithy, heard or saw anything that could interest the student of the occult. Pleasant lazy days succeeded each other, we bathed and rambled and played piquet of an evening, and incidentally we made friends with the vicar. He was an interesting man, full of curious lore concerning local legends and superstitions, and one night, when in our ripened acquaintanceship he had dined with us, he asked Philip directly whether either of us had experienced anything unusual during our tenancy.

Philip nodded towards me.

“My friend saw most,” he said.

“May I hear it?” asked the vicar.

When I had finished, he was silent awhile.

“I think the—shall we call it explanation?—is yours by right,” he said. “I will give it you if you care to hear it.”

Our silence, I suppose, answered him.

“I remember meeting you two on the day after your arrival here,” he said, “and you inquired about the tombstone in the churchyard erected to the memory of George Hearne. I did not want to say more of him then, for a reason that you will presently know. I told you, I recollect, perhaps rather hurriedly, that it was Mrs. Hearne’s husband who was buried there. Already, I imagine, you guess that I concealed something. You may even have guessed it at the time.”

He did not wait for any confirmation or repudiation of this. Sitting out on the terrace in the deep dusk, his communication was very impersonal. It was just a narrating voice, without identity, an anonymous chronicle.

“George Hearne succeeded to the property here, which is considerable, only two years before his death. He was married shortly after he succeeded. According to any decent standard, his life both before and after his marriage was vile. I think—God forgive me if I wrong him—he made evil his good; he liked evil for its own sake. But out of the middle of the mire of his own soul there sprang a flower: he was devoted to his wife. And he was capable of shame.

“A fortnight before his—his death, she got to know what his life was like, and what he was in himself. I need not tell you what was the particular disclosure that came to her knowledge; it is sufficient to say that it was revolting. She was here at the time; he was coming down from London that night. When he arrived he found a note from her saying that she had left him and could never come back. She told him that he must give her opportunity for her to divorce him, and threatened him with exposure if he did not.

“He and I had been friends, and that night he came to me with her letter, acknowledged the justice of it, but asked me to intervene. He said that the only thing that could save him from utter damnation was she, and I believe that there he spoke sincerely. But, speaking as a clergyman, I should not have called him penitent. He did not hate his sin, but only the consequences of it. But it seemed to me that if she came back to him, he might have a chance, and next day I went to her. Nothing that I could say moved her one atom, and after a fruitless day I came back, and told him of the uselessness of my mission.

“Now, according to my view, no man who deliberately prefers evil to good, just for the sake of wickedness, is sane, and this refusal of hers to have anything more to do with him, I fully believe upset the unstable balance of his soul altogether. There was just his devotion to her which might conceivably have restored it, but she refused—and I can quite understand her refusal—to come near him. If you knew what I know, you could not blame her. But the effect of it on him was portentous and disastrous, and three days afterwards I wrote to her again, saying quite simply that the damnation of his soul would be on her head unless, leaving her personal feelings altogether out of the question, she came back. She got that letter the next evening, and already it was too late.

“That afternoon, two years ago, on the 15th of August, there was washed up in the harbour here a dead body, and that night George Hearne took a ladder from the fruit-wall in the kitchen garden and hanged himself. He climbed into one of the pollarded limes, tied the rope to a bough, and made a slip-knot at the other end of it. Then he kicked the ladder away.

“Mrs. Hearne meantime had received my letter. For a couple of hours she wrestled with her own repugnance and then decided to come to him. She rang him up on the telephone, but the housekeeper here, Mrs. Criddle, could only tell her that he had gone out after dinner. She continued ringing him up for a couple of hours, but there was always the same reply.

“Eventually she decided to waste no more time, and motored over from her mother’s house where she was staying at the north end of the county. By then the moon had risen, and looking out from his bedroom window she saw him.”

He paused.

“There was an inquest,” he said, “and I could truthfully testify that I believed him to be insane. The verdict of suicide during temporary insanity was brought in, and he was buried in the churchyard. The rope was burned, and the ladder was burned.”

The parlourmaid brought out drinks, and we sat in silence till she had gone again.

“And what about the telephone my friend heard?” asked Philip.

He thought a moment.

“Don’t you think that great emotion like that of Mrs. Hearne’s may make some sort of record,” he asked, “so that if the needle of a sensitive temperament comes in contact with it, a reproduction takes place? And it is the same perhaps about that poor fellow who hanged himself. One can hardly believe that his spirit is bound to visit and revisit the scene of his follies and his crimes year by year.”

“Year by year?” I asked.

“Apparently. I saw him myself last year, Mrs. Criddle did also.”

He got up.

“How can one tell?” he said. “Expiation, perhaps. Who knows?”

E. F. Benson (1867 — 1940)