Public Domain Text: James Lamp by E. F. Benson

James Lamp is a short story written by E. F. Benson. It was first published in Weird Tales (June 1930).

The story is told in the third person. The narrator begins by providing details about his friend, John Storely, and then goes on to describe the strange events that happened during a visit to Storely’s home in the country.

Storely also has a home in London and generally spends most of the Winter months there. He finds city life preferable to country life when the days are short and the weather is cold and damp.

When either of his homes is going to be empty for a long time, Storely entrusts their care to his servant James Lamp, who takes care of them along with his wife who serves as a housekeeper.

When Storely returns to his country house for a brief weekend visit, he invites his friend to join him. However, he warns him that Lamps’ wife has gone missing and is presumed to have eloped with her lover.

However, the narrator encounters Mrs Lamp in a dark foggy street and sends Storely after her. The woman vanishes before either man can speak to her.

Gradually, the narrator begins to believe the woman he saw may have been a ghost.

About E. F. Benson

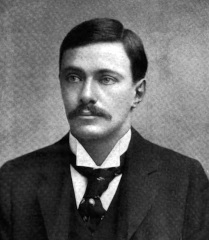

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

John Lamp

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

Mr. John Storely, bachelor, of middle-age, and very comfortable circumstances, had lately retired from his extensive practice in London, while still in sound health and activity, for, as he justly remarked, what was the good of keeping in harness till you were too old and infirm to enjoy a well-earned leisure. He still spent most of the year in town, for he was of sociable habits, and the country, so he thought, was a very dreary place for a single man, who neither hunted nor shot, from the time when the autumn leaves began to fall until spring had definitely established itself again. There were fogs and darkness, it was true, in London, but there were also gas-lamps and pavements, and a walk along lighted streets to his club, where he would find a rubber of bridge before dinner was infinitely preferable to a tramp in dim and dripping country lanes, and the return again to his house at Trench, a small country-town at the edge of the Romney Marsh, where he would spend a solitary evening. Winter days in the country closed in early, a servant came round and drew the curtain, and then you were shut up in your box till morning, whereas in London there were many friends about, and pleasant dinners at home or abroad, amusements of all sorts ready to hand. As for going to some winter resort like the Riviera, the thought was anathema to him. People went to the Riviera to get sunshine and all they got was blizzards and possibly pneumonia. London, to his mind, was the ideal place in which to spend the winter.

He had therefore arranged his life on these lines. His delightful little house down at Trench was in the hands of a caretaker and his wife from November till April; during the late spring and earlier autumn Storely was often down there for a week or a week-end, and then Mr. and Mrs. Lamp looked after him, she as cook with housemaid’s help got in from the town, and her husband as general manservant. When summer arrived he moved his London household down there for four or five solid months, while the caretakers took charge of his house in London. Like a sensible man, he knew that a motor, now that he had no rounds of professional visits to pay, was a mere encumbrance in town, and accordingly he left his car at Trench throughout the winter.

He had bought this house some three years ago, just before he retired, and I had often been down to stay with him for these week-ends of spring and autumn, and for longer periods during the summer. It stood half-way down one of those steep, cobbled streets for which Trench is famous, and was the most adorable establishment. Three small gables of timber and rough-cast faced the road, and from the front it seemed rather shut in, but once inside, it opened out into a dignified and spacious privacy. There was a little panelled hall with an oak staircase leading up to the first floor, and on each side of it a big ceiling-beamed room with wide open fireplace, and all looked out at the back on to a full acre of unexpected lawn and garden, screened by high red brick walls from the intrusion of neighbouring eyes. He had done the house up with due regard for its picturesque antiquity but with an equal regard for all possible demands of modern comfort: electric light was most conveniently installed, central heating supplemented the log-burning, open hearths, and the three big bedrooms on the first floor had each its own bathroom. Just as perfect were the ministrations of the care-taking couple when Storely went down for the shorter periods of his sojourn, Lamp, deft and silent-footed, and his wife, mostly invisible in her kitchen, manifesting her presence there by the most admirable meals. One saw her occasionally when she came up after breakfast to submit to Storely her proposed caterings for the day, a handsome, high-coloured woman, with a hard smart air about her, and considerably younger than her husband; sometimes one met her in the town with her marketing-basket, and many smiles and ribands.

I was engaged in the spring of this year to spend a week at Easter with my friend. A few days before I met him in the card-room at the club, and we cut into a table of bridge together. After a couple of rubbers we cut out again, and he beckoned me aside to a remote corner, where we could talk privately.

“Upsetting news from Trench yesterday morning,” he said. “A couple of days ago Mrs. Lamp, my caretaker’s wife; do you remember her?”

“Indeed, I do,” said I.

“Well, she disappeared, and has not been seen since. She used often to take long walks in the country by herself when the two were alone there in the winter, and a couple of days ago she appears to have started for one, as was quite usual with her, but when the evening closed in and it had got dark she had not returned. Lamp behaved very sensibly and properly: he went to a house or two in the town where his wife sometimes visited, but no one had seen her, and about eleven o’clock that night, now feeling very uneasy, he went to the police-station, and told the inspector that she was still missing. They telephoned to various villages in the neighbourhood, and to wayside stations on the line, but got no news of her; beyond that there was nothing more that could be done that night. Morning came, but there was still no sign of her, and Lamp telephoned to me to say what had happened. I went down there after breakfast this morning, and he disclosed to me a state of things of which I had no suspicion at all.”

“A man?” I asked.

“Yes; the foreman in some builder’s establishment in Hastings. Lamp and his wife had had words about him before, and a fortnight ago, in consequence of what he had seen, he had told the man he mustn’t set foot in the house again, but he had been seen in Trench on the day that his wife disappeared. All this Lamp told me, but he had not mentioned it to the police, since naturally he did not want scandal to get about. But now, when his wife disappeared, it seemed to us that it was necessary to let the police know, in case she had gone to him, and I sent for the inspector and told him about it. He made enquiries in Hastings, but nothing could be heard about her. The foreman admitted that he had been in Trench that day, but said he had not seen her. He admitted also, when he was closely questioned, that he and Mrs. Lamp had agreed that she should leave her husband and come to live with him. They intended to marry if Lamp would divorce her.”

“And how is Lamp taking it?” I asked.

“My own opinion is that he will be much happier without her. He believes that she has gone to this foreman, though why, if she has, they should try to make a secret about it, it is impossible to say. But that is his firm conviction. The two, so Lamp told me, have had a horrible time of it this winter, and if she was never heard of again I don’t think he would be sorry. She certainly has made their life together a wretched business.”

“But at present there’s no clue as to what has happened to her?” I asked.

“Absolutely none. The police expect loss of memory and sense of identity, as they always do when anyone disappears, and they’re keeping an eye on this man in Hastings. It was painful to hear Lamp tell the story of all this, but he did it very frankly, and they’re convinced that he has told all he knows. Apparently there is quite sufficient evidence for him to get his divorce, and if she tries to come back to him again, he means to do it.”

Storely got up.

“I thought I would just tell you,” he said, “for we’ll go down there as arranged the day after to-morrow. Lamp says he can get a woman from Trench to come in and cook, and like a sensible fellow he wants to get back to work again. Far the best thing for him to do.”

So we went down together as had been settled: Trench looked more attractive and idyllic than ever in this sudden burst of spring and warm April weather. Its red-brick houses climbing up the hill glowed in the mellow sunshine, its gardens were gay with fresh leaf and blossom. In the reclaimed marsh-land outside, the hawthorn hedges were in bud, innumerable lambs bleated and gambolled over the meadows, and the woods in the country round about were tapestried with primroses and anemone and curled bracken-shoots. It is a land of greenness and streams and slow rivers wending over the levels to the sea: on the east side of the small town the Roop wanders along under the steep hills, on the west side the bigger Inglis sweeps widely past the south of the town and joins the other. Half-way down this western slope of the hill was Storely’s house, looking out on to the narrow cobbled street lined with gabled cottages. At the bottom of it, not fifty yards from his door stand granaries and warehouses on the banks of the River Inglis, up which, at high tide, vessels of considerable tonnage can come to anchor and discharge their freights. The road to Hastings passes along this bank, then crosses the river by a bridge, at the side of which are sluice-gates to be opened or shut to let through or limit the tide.

We strolled out after tea on the day of our arrival, Storely and I, across this bridge. The tide was low, and one could see how deeply the flows and ebbs of the water had scooped out, below the sluice, great holes lined with soft shining mud, while others deeper yet were still undiscovered. From there we strolled into a path leading across the daisied meadows of the marsh and bordered by dykes still brimming with the winter rains and fringed with the new growth of the reeds that pricked up through the dead raffle of last year. The sun was low to its setting, and now after this hot day skeins of mist were beginning to form over the level in the chill of the evening, shallow at present but so opaque that at a little distance they appeared like sheets of grey flood-water through which stood up the trunks of the scattered thorn-trees. Then turning we set our faces towards Trench, the topmost houses of which, set on the hill, still glowed in the sunlight though now on this lower land we walked in the shadow. As we crossed the bridge over the Inglis the mist had formed very thick upon the river, and like a tide had crept across the quay-side, and out in the Channel fog-horns were mooing. We stepped briskly across the vapourous lake to the foot of the steep cobbled street, half-way up which stood Storely’s house. The pavement was narrow, not giving room for two to walk abreast, and I fell behind him. Just here there joined this street on our right a narrow footway faced with houses leading round to the south face of the hill, and as we passed this, I saw there was a woman standing there. Her back was towards me, and she was looking up the street in the direction of Storely’s house. He was a few paces ahead of me, and as I came directly opposite her she turned, and I felt sure that her face was familiar to me though for the moment I could not recollect who she was. Then close on the heels of that came recognition, and I knew that she was Mrs. Lamp. It was dusk, it was misty and I could not see her face very precisely, but I had no doubt of her identity.

I took a few quick steps forward, and touched Storely on the shoulder.

“Turn round,” I said quietly, “and have a look at that woman standing at the corner just below. See if you recognize her!”

He turned, peering into the dusk.

“But I don’t see any woman at all,” he said. “There’s no one there.”

I turned also, and even as Storely had said, she was no longer there. I ran back to the corner where the footpath joined the street, and there she was moving up it away from us. I beckoned to him, pointing up this footway.

“But what’s all this about?” he asked.

“I want you to see her,” said I. “She’s walking up that path. Be quick, or she’ll have gone.”

He laughed.

“But I really can’t go in pursuit of women in the dusk about the streets of Trench,” he said. “Who is it that you want me to identify?”

“I feel sure it’s Mrs. Lamp,” I answered.

Instantly he joined me.

“What? Mrs. Lamp?” he said in a changed voice. “Where? That woman ahead there? I’ll soon see.”

I waited at the corner while he went quickly after her. They both passed out of sight round a bend in the footpath. In a couple of minutes he returned.

“I lost sight of her somehow,” he said. “She must have turned into one of those houses there, though I didn’t see her do so. Are you sure it was she?”

“No: that’s why I wanted you to see her. But if it wasn’t she, it was somebody most extraordinarily like her.”

He thought a moment.

“I think we had better not say anything either to Lamp or the police at present,” he said. “We’re not certain enough, for it’s dusk, and after all you’ve only seen her a few times before. But if it is she, you may depend upon it that someone else will see her. We shall soon know.”

Lamp was in the sitting-room when we got to the house. It was already chilly, and he had just put a match to the fire of logs and brushwood on the hearth, had turned the lights on, and was now drawing the curtains; I thought he peered oddly and intently up and down the street before he pulled the heavy folds across the windows. Somehow the sight (or so I believed) of the missing woman, had roused an uneasy feeling in my mind, but how utterly illogical and senseless that was. For if it was she, all fear of her having come to some ill end was over, while if it was not she, there could be nothing unsettling in having seen some other woman who strangely reminded me of her. But it was odd, it was also regrettable that Storely had lost sight of her like that. If he had only had one decent look at her, the question would have been settled.

We spent a quiet evening, playing a rather serious game of chess after dinner. About ten o’clock, while the game was still in progress, Lamp brought in a tray of water and spirits, and while he was in the room their came a soft tapping, very light, against the low diamond-paned window behind the curtain, looking out onto the street. At the moment he was pouring some whisky into a glass, and looking up, I saw he had paused as if listening.

“What was that tapping?” asked Storely absently, as he considered his move.

“A butterfly, sir,” said Lamp. “I saw one fluttering about the window when I drew the curtains this evening.”

“Must have been encouraged to come out after the winter by this hot sun,” said Storely. “That’s all we shall want, Lamp. You can go to bed: I’ll put out the lights.”

Lamp left us, Storely made his move, and as I was considering mine the soft tapping came again. He rose and went to the window.

“It sounded just as if someone was tapping at the pane from outside,” he said.

He parted the curtain and looked out. There was silence for a moment.

“Just come here,” he said to me.

The light from inside the room as he drew the curtain back cast a field of illumination into the street, and outside looking into the window was the figure of a woman. I could see her face clearly, and it was certainly that of her whom I had seen that evening in the flesh as we returned from our walk. She looked at Storely, then at me, and then between us into the room behind as if she was wanting somebody but not one of us.

“Stop there and watch her,” said Storely to me, and he went out into the hall, and I heard him unlock the front door. The woman turned at the sound, and moved away from the window into the darkness. I heard Storely’s step on the pavement outside, and he beckoned and called to me through the window. “She’s gone,” he said. “Did you see which way she went?”

“I think down the hill,” I said, and I heard his steps following her. I went out after him into the street. It was an exceedingly dark night and misty: I could not see more than a few yards in any direction. The light in the hall shone out of the open door, and I saw also that at the top of the house was a lit window against which was framed a man’s head. Lamp had evidently gone up to bed, and, hearing the sound of Storely’s voice in the street, was looking out. In a few minutes I heard Storely’s returning steps.

“Come in,” he said, “I lost her at once, for the fog is fearfully thick at the bottom of the hill.”

He closed the door, and we sat down again on either side of our chess-board. Though the game was only half over he began putting the pieces back in the box.

“What am I to do?” he said. “There’s no doubt who it was. But why is she here, and why does she come at night and tap at the window and then make off again? Did you see her looking between us as if she wanted somebody else? And if it’s Lamp she wants, why doesn’t she come and ask for him? Anyhow I must go round to the police station in the morning to tell them they needn’t make any further enquiries about her, as she has certainly been seen. They aren’t concerned about her connubial affairs, but only about her disappearance, and now that we’re sure she’s alive there’s nothing more for them to investigate. Hullo, I’ve scrapped our game.” He stared into the smouldering embers of the fire for a moment in silence, then wheeled round to me.

“It’s all rather odd,” he said. “I’ve no doubt it is she; absolutely none. But why did she come here at all, if it was only to sheer off again in that mysterious way? I wonder if by any chance Lamp has seen her? Surely he would have told me if he had.”

Even as he spoke the door opened and Lamp came in.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, “but I had just gone up to bed when I heard you go out and call from the street. I came down to see if you were wanting anything.”

Storely pointed to the window.

“Your wife was standing outside there a few minutes ago,” he said. “I went out to see what she was doing here.”

I was watching Lamp closely now, for an idea, wild and fantastic no doubt, had entered my head. He was standing by the electric light, and I saw sudden beads of perspiration break out on his forehead, and his lips moved as if for speech, but no words came. But he quickly recovered himself.

“Indeed, sir?” he said. “And may I ask if you got speech with her?”

“No, she disappeared in the fog before I could come up with her. But you can dismiss from your mind now any fear that some accident has happened to her. I shall go round to the police-station in the morning, and tell them they need not continue their search for her.”

“Thank you very much, sir,” said Lamp. “But I was never really afraid of that. I always thought that she had gone off with that man of hers. And there’s another thing, sir, if you wouldn’t mind my mentioning it. I’ll get all her clothes and bits of things ready packed for her, if it’s that she’s hanging about for, but I hope you won’t allow her into the house again after what she’s done.”

“No, that’s reasonable,” said Storely, “I won’t let her bother you if I can help it. You haven’t seen her I suppose?”

Again I watched Lamp. I saw him gulp in his throat before he spoke, and moisten his lips.

“No, sir, and I don’t want to,” he said.

Storely nodded.

“That’s all then, Lamp,” he said. “I’ll go to the police to-morrow.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Lamp again. “Of course it’s a great relief to me to learn that she’s come to no bodily harm.”

“But you said you weren’t afraid of that,” said Storely.

“I wasn’t, sir,” he said. “But it’s another thing to be certain of it.”

Now Storely, like most people accounted sensible, both distrusts and despises all theories that admit the existence of occult and unexplained phenomena. So I did not say anything to him about the notion which had entered my head, and which proved, when I had got to bed, to be very uncomfortably established there. In a word, I did not believe that the woman we had both seen was the living and material presentment of Lamp’s wife. I believed that it was some bodiless phantom of her, and that Lamp also had seen her, and that he knew it was not her actual bodily presence we had all beheld. He had seen, I felt sure, what we had seen, and was terrified of it. His explanation and suggestion were certainly plausible enough; he would pack up her clothes and have them ready, and it was natural that he did not want her to come inside the house at all. But it was not the thought of that which made the sweat to stand on his forehead, and his throat to gulp, but something very different. The thought haunted me: often I half dropped off to sleep, but as many times I woke again with the sense that there was something creeping up to the house, like the fog that was now thick outside my window, and seeking admittance. And often in these wakenings, I heard from the room above, which was Lamp’s, a soft footfall going backwards and forwards. It went to the window, and then I heard the creak of the opening sash: then the window was closed again, and the blind drawn down over it. But towards morning I slept more soundly, and woke to find him already in my room, deftly putting out my clothes.

Storely went off to the police-station directly after breakfast. He had told Lamp to bring the car round from the garage which adjoined the house, for we were to spend the day on the links. The fog had quite cleared under a breath of north wind, the morning was of a crystalline brightness, and while waiting for Storely I strolled down the street and out on to the river-side. In this radiant day of spring I almost thought that my uneasy imaginings were but nightmare notions, and unreal as dreams. Certainly they had left the surface of my conscious mind, and I cared little whether they had dispersed altogether or were lurking in the shadows within, so long as they did not trouble me. When I got back to the house the car was standing at the door, and casually glancing into it, as I passed, I thought I saw that huddled up on the back seat was sprawling the figure of a woman. The impression was absolutely momentary for at once it restored itself into a medley of coat and rug with a patch of oval sunlight for a face. A good lesson, thought I, of the tricks the imagination can play, for clearly this was a piece of that nightmare stuff which had been troubling me, and which had no existence in fact.

It was dusk when we drew up at the door again that evening after a salubrious day in the open. A tranquil, pleasant fatigue possessed me: I looked forward to my bath and my dinner, and cosy fireside hours before bedtime. Storely had passed into the house, leaving the front door open, and I lingered at the threshold a minute, watching Lamp back the car into the garage. As I stood there, I felt something brush by me, and pass invisibly into the house. Simultaneously I heard Storely’s voice from the hall inside call out, “Hullo, what’s that?” I came in, shutting the door.

“What was it?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I was reading my letters at the table, when something brushed by me, and I thought it was you. But there was nothing to be seen. The door into the sitting-room swung open and closed again. Where’s Lamp?”

“He’s putting the car into the garage,” I said.

“But something did go in there,” he said. “Turn on the light.”

I found the switch and turned it, and the dark room leaped into brightness. But it was quite empty.

“Odd,” he said. “It must have been a draught. But it felt more solid than that.”

“It brushed by me, too, as I stood in the doorway,” I said.

“Of course it was a draught then,” he said. “Strong eddies of air often come up this narrow street. I will shut them all out.”

We drew our chairs up near the fire, for the evening had turned chilly again. I had looked forward to this drowsy hour, with the evening paper to glance at, and a book to doze over, but instead I found myself eagerly alert. But I could not give my attention to my book because something was going on far more arresting than anything which the world of books could contain. It was no subjective unrest that kept me thus on wires; it was that the whole of my mind was waiting for something quite outside myself to develop, and it, whatever it was, was in the room. It watched, it moved about, it waited, and now the air was growing misty, and I supposed that the fog had formed again outside, and was leaking in. But when I went up to dress I looked out from my bedroom window, and saw that the sky overhead was full of bright-burning stars, and that the street below, though dark, was so clear that I could see the dew which had fallen and lay on the cobbles shimmering in the starlight.

During dinner I noticed that Storely as well as I was observing Lamp. The man was evidently not himself, ordinarily deft-handed and silent-footed, he clattered with his dishes, and when he stood waiting for us to eat our course he kept glancing uneasily round. At the end of the dinner, as he poured out a glass of port for his master, he made some awkward jerk with his hand, and upset it. An impatient exclamation was on the tip of Storely’s tongue, but he checked it.

“Anything the matter, Lamp?” he asked, as he mopped up the spilt wine. “Aren’t you well?”

“No, sir, I’m right enough,” he said. “But it’s queer how the house is full of fog. The kitchen: why you can hardly see across it.”

Presently we were back in the sitting-room where the chess-board was already set. The woman who came in to cook did not sleep in the house, and soon I heard the tapping of her steps down the flagged kitchen passage, and the opening and shutting of the back door: then came the sound of Lamp locking and bolting it. During the next hour, while our game was in progress, he must have come into the room half a dozen times: his hands trembled as he swept up the hearth, his face was ashen, and it was evident that he was in a state of acute nervous tension, and made any excuse to himself for coming into the room instead of biding alone in the kitchen. Finally, Storely told him that we wanted nothing more that night, and that he could get to bed. But we heard him moving about the house overhead, and when an hour later we finished our game, and went upstairs, he was still astir in the room above me.

I got to bed and instantly fell asleep, and woke again with the faint light of early dawn shining in through the window, knowing that some noise had aroused me. There was the sound of steps coming from the floor above, and they passed my door, and went on downstairs into the hall. I got out of bed, turned on my light and went to the door and opened it. But not a yard could I see in front of me, so dense was the fog that filled the passage. Yet somebody—were there not the steps of two people?—had just passed quickly by as if it was full daylight. Then suddenly from below came the sound of voices and with a thrill of nameless horror I heard that one of them was the voice of a woman.

“So now you’ve got to come with me, James Lamp,” it said, “and take me where you took me before. You’ll drive me down in the car, as you drove me before, and you’ll come down into the water where you threw me, and I’ll be waiting for you there, so close and loving.”

Then came the other voice. It was Lamp’s voice, and it rose to a scream as it spoke.

“No, no,” he cried. “No, not that. I won’t come. I tell you. Ah, take your hand off me: it’s hot as fire, and I can’t bear it.”

“Come on then obediently,” said the other. “It’s cool in the water.”

The door of Storely’s room, just opposite mine, opened. I heard him click on the switch in the passage, and very faintly above our heads, in the dense air, there shone out white but hardly luminous the electric light from the ceiling.

“Ah, you’ve heard it, too,” he said, seeing me. “What is it? What’s happening? There were voices, and a yell. And then the front door opened and shut again. Come down!”

We groped our way along the passage, but on the stairs it was absolutely pitch dark. There was a switch somewhere there, but he could not find it, and he went back to his room to get a box of matches. With the help of that light he got hold of the switch, but even so we had to proceed with shuffling steps, so dense was the fog. We crossed the hall, and after fumbling at the front door, he threw it open, and there came in the faint clear light of the dawn. Even as we stood on the threshold the motor emerged from the garage close by, and I saw that by the side of Lamp, who drove it, there sat a woman. It turned and went swiftly down the street towards the river.

“But, good God, what’s happening?” cried Storely. “That’s Lamp. But where is he going? And who was that woman with him. Couldn’t you see?”

And in the grey light of morning we read the answering horror in each other’s faces.

The rest of the story, as it came out at the inquest held next day at Trench, is probably known to my readers. Storely’s empty car was found by a labourer going out to his work drawn up on the bridge across the river Inglis, and the deep pool below the sluice was dragged. Two bodies were found there, one of a woman, the other of James Lamp. The woman’s body had evidently been in the water for several days, his only for a few hours. But her hands were so tightly locked round the throat of the man that it was with difficulty that the two could be separated. In the woman’s head was a wound caused by a revolver bullet: it had entered the back of her skull and was embedded in her brain. Medical evidence showed that she was certainly dead before she had been thrown into the water, and round her neck was a heavy iron weight. The body was quite recognizable as being that of Lamp’s wife.

E. F. Benson (1867 — 1940)