Public Domain Text: Little Joe Gander by Sabine Baring-Gould

Little Joe Gander is a short story by Sabine Baring-Gould. It was first published in his short story collection A Book of Ghosts (1904).

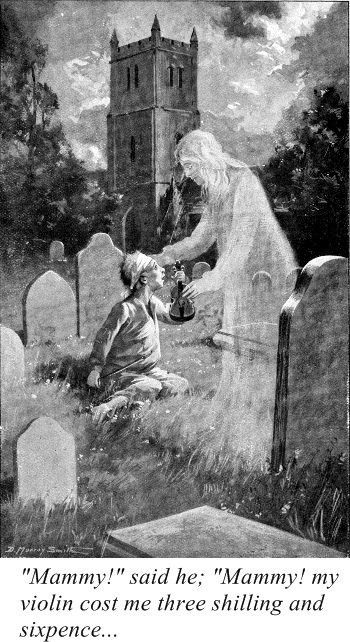

A Book of Ghosts was illustrated by D. Murray Smith . This page includes a copy of his illustration for Little Joe Gander.

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

Little Joe Gander by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

“There’s no good in him,” said his stepmother, “not a mossul!” With these words she thrust little Joe forward by applying her knee to the small of his back, and thereby jerking him into the middle of the school before the master. “There’s no making nothing out of him, whack him as you will.”

Little Joe Lambole was a child of ten, dressed in second-hand, nay, third-hand garments that did not fit. His coat had been a soldier’s scarlet uniform, that had gone when discarded to a dealer, who had dealt it to a carter, and when the carter had worn it out it was reduced and adapted to the wear of the child. The nether garments had, in like manner, served a full-grown man till worn out; then they had been cut down at the knees. Though shortened in leg, they maintained their former copiousness of seat, and served as an inexhaustible receptacle for dust. Often as little Joe was “licked” there issued from the dense mass of drapery clouds of dust. It was like beating a puff-ball.

“Only a seven-month child,” said Mrs. Lambole contemptuously, “born without his nails on fingers and toes; they growed later. His wits have never come right, and a deal, a deal of larruping it will take to make ’em grow. Use the rod; we won’t grumble at you for doing so.”

Little Joe Lambole when he came into the world had not been expected to live. He was a poor, small, miserable baby, that could not roar, but whimpered. He had been privately baptised directly he was born, because, at the first, Mrs. Lambole said, “The child is mine, though it be such a creetur, and I wouldn’t like it, according, to be buried like a dog.”

He was called Joseph. The scriptural Joseph had been sold as a bondman into Egypt; this little Joseph seemed to have been brought into the world to be a slave. In all propriety he ought to have died as a baby, and that happy consummation was almost desired, but he disappointed expectations and lived. His mother died soon after, and his father married again, and his father and stepmother loved him, doubtless; but love is manifested in many ways, and the Lamboles showed theirs in a rough way, by slaps and blows and kicks. The father was ashamed of him because he was a weakling, and the stepmother because he was ugly, and was not her own child. He was a meagre little fellow, with a long neck and a white face and sunken cheeks, a pigeon breast, and a big stomach. He walked with his head forward and his great pale blue eyes staring before him into the far distance, as if he were always looking out of the world. His walk was a waddle, and he tumbled over every obstacle, because he never looked where he was going, always looked to something beyond the horizon.

Because of his walk and his long neck, and staring eyes and big stomach, the village children called him “Gander Joe” or “Joe Gander”; and his parents were not sorry, for they were ashamed that such a creature should be known as a Lambole.

The Lamboles were a sturdy, hearty people, with cheeks like quarrender apples, and bones set firm and knit with iron sinews. They were a hard-working, practical people who fattened pigs and kept poultry at home. Lambole was a roadmaker. In breaking stones one day a bit of one had struck his eye and blinded it. After that he wore a black patch upon it. He saw well enough out of the other; he never missed seeing his own interests. Lambole could have made a few pence with his son had his son been worth anything. He could have sent him to scrape the road, and bring the manure off it in a shovel to his garden. But Joe never took heartily to scraping the dung up. In a word, the boy was good for nothing.

He had hair like tow, and a little straw hat on his head with the top torn, so that the hair forced its way out, and as he walked the top bobbed about like the lid of a boiling saucepan.

When the whortleberries were ripe in June, Mrs. Lambole sent Joe out with other children to collect the berries in a tin can; she sold them for fourpence a quart, and any child could earn eightpence a day in whortleberry time; one that was active might earn a shilling.

But Joe would not remain with the other children. They teased him, imitated ganders and geese, and poked out their necks and uttered sounds in imitation of the voices of these birds. Moreover, they stole the berries he had picked, and put them into their own cans.

When Joe Gander left them and found himself alone in the woods, then he lay down among the brown heather and green fern, and looked up through the oak leaves at the sky, and listened to the singing of the birds. Oh, wondrous music of the woods! the hum of the summer air among the leaves, the drone of the bees about the flowers, the twittering and fluting and piping of the finches and blackbirds and thrushes, and the cool soft cooing of the wood pigeons, like the lowing of aerial oxen; then the tapping of the green woodpecker and a glimpse of its crimson head, like a carbuncle running up the tree trunk, and the powdering down of old husks of fir cones or of the tender rind of the topmost shoot of a Scottish pine; for aloft a red squirrel was barking a beautiful tree out of wantonness and frolic. A rabbit would come forth from the bracken and sit up in the sun, and clean its face with the fore paws and stroke its long ears; then, seeing the soiled red coat, would skip up—little Joe lying very still—and screw its nose and turn its eyes from side to side, and skip nearer again, till it was quite close to Joe Gander; and then the boy laughed, and the rabbit was gone with a flash of white tail.

Happy days! days of listening to mysterious music, of looking into mysteries of sun and foliage, of spiritual intercourse with the great mother-soul of nature.

In the evenings, when Gander Joe came without his can, or with his can empty, he would say to his stepmother: “Oh, steppy! it was so nice; everything was singing.”

“I’ll make you sing in the chorus too!” cried Mrs. Lambole, and laid a stick across his shoulders. Experience had taught her the futility of dusting at a lower level.

Then Gander Joe cried and writhed, and promised to be more diligent in picking whortleberries in future. But when he went again into the wood it was again the same. The spell of the wood spirits was on him; he forgot about the berries at fourpence a quart, and lay on his back and listened. And the whole wood whispered and sang to him and consoled him for his beating, and the wind played lullabies among the fir spines and whistled in the grass, and the aspen clashed its myriad tiny cymbals together, producing an orchestra of sound that filled the soul of the dreaming boy with love and delight and unutterable yearning.

It fared no better in autumn, when the blackberry season set in. Joe went with his can to an old quarry where the brambles sent their runners over the masses of rubble thrown out from the pits, and warmed and ripened their fruit on the hot stones. It was a marvel to see how the blackberries grew in this deserted quarry; how large the fruit swelled, how thick they were—like mulberries. On the road side of the quarry was a belt of pines, and the sun drew out of their bark scents of unsurpassed sweetness. About the blackberries hovered spotted white and yellow and black moths, beautiful as butterflies. Butterflies did not fail either. The red admiral was there, resting on the bark of the trees, asleep in the sun with wings expanded, or drifting about the clumps of yellow ragwort, doubtful whether to perch or not.

Here, hidden behind the trees, among the leaves of overgrown rubble, was a one-story cottage of wood and clay, covered with thatch, in which lived Roger Gale, the postman.

Roger Gale had ten miles to walk every morning, delivering letters, and the same number of miles every evening, for which twenty miles he received the liberal pay of six shillings a week. He had to be at the post office at half-past six in the morning to receive the letters, and at seven in the evening to deliver them. His work took him about six hours. The middle of the day he had to himself. Roger Gale was an old soldier, and enjoyed a pension. He occupied himself, when at home, as a shoemaker; but the walks took so much out of him, being an old man, that he had not the strength and energy to do much cobbling when at home. Therefore he idled a good deal, and he amused his idle hours with a violin. Now, when Joe Gander came to the quarry before the return of the postman from his rounds, he picked blackberries; but no sooner had Roger Gale unlocked his door, taken down his fiddle, and drawn the bow across the strings, than Joe set down the can and listened. And when old Roger began to play an air from the Daughter of the Regiment, then Joe crept towards his cottage in little stages of wonderment and hunger to hear more and hear better, much in the same way as now and again in the wood the inquisitive rabbits had approached his red jacket. Presently Joe was seated on the doorstep, with his ear against the wooden door, and the blackberries and the can, and stepmother’s orders and father’s stick, and his hard bed and his meagre meals, even the whole world had passed away as a scroll that is rolled up and laid aside, and he lived only in the world of music.

Though his great eyes were wide he saw nothing through them; though the rain began to fall, and the north-east wind to blow, he felt nothing: he had but one faculty that was awake, and that was hearing.

One day Roger came to his door and opened it suddenly, so that the child, leaning against it, fell across his threshold.

“Whom have we here? What is this? What do you want?” asked the postman.

Then Gander Joe stood up, craning his long neck and staring out of his goggle eyes, with his rough flaxen hair standing up in a ruffle above his head and his great stomach protruded, and said nothing. So Roger burst out laughing. But he did not kick him off the step; he gave him a bit of bread and a drop of cider, and presently drew from the boy the confession that he had been listening to the fiddle. This was flattering to the postman, and it was the initiation of a friendship between them.

But when Joe came home with an empty can and said: “Oh, steppy, Master Roger Gale did fiddle so beautiful!” the woman said: “Fiddle! I’ll fiddle your back pretty smartly, you idle vagabond”; and she was a truthful woman who never fell short of her word.

To break him of his bad habits—that is, of his dreaminess and uselessness—Mrs. Lambole took Joe to school.

At school he had a bad time of it. He could not learn the letters. He was mentally incapable of doing a subtraction sum. He sat on a bench staring at the teacher, and was unable to answer an ordinary question what the lesson was about. The school-children tormented him, the monitor scolded, and the master beat. Then little Joe Gander took to absenting himself from school. He was sent off every morning by his stepmother, but instead of going to the school he went to the cottage in the quarry, and listened to the fiddle of Roger Gale.

Little Joe got hold of an old box, and with a knife he cut holes in it; and he fashioned a bridge, and then a handle, and he strung horsehair over the latter, and made a bow, and drew very faint sounds from this improvised violin, that made the postman laugh, but which gave great pleasure to Joe. The sound that issued from his instrument was like the humming of flies, but he got distinct notes out of his strings, though the notes were faint.

After he had played truant for some time his father heard what he had done, and he beat the boy till he was like a battered apple that had been flung from the tree by a storm upon a road.

For a while Joe did not venture to the quarry except on Saturdays and Sundays. He was forbidden by his father to go to church, because the organ and the singing there drove him half crazed. When a beautiful, touching melody was played his eyes became clouded and the tears ran down his cheeks; and when the organ played the “Hallelujah Chorus,” or some grand and stirring march, his eyes flashed, and his little body quivered, and he made such faces that the congregation were disturbed and the parson remonstrated with his mother. The child was clearly imbecile, and unfit to attend divine worship.

Mr. Lambole got an idea into his head, he would bring up Joe to be a butcher, and he informed Joe that he was going to place him with a gentleman of that profession in town. Joe cried. He turned sick at the sight of blood, and the smell of raw meat was abhorrent to him. But Joe’s likings were of no account with his father, and he took him to the town and placed him with a butcher there. He was invested in a blue smock, and was informed that his duties would consist in taking meat about to the customers. Joe was left. It was the first time he had been from home, and he cried himself to sleep the first night, and he cried all the next day when sent around with meat on his shoulder.

Now on his journey through the streets he had to pass the window of a toy-shop. In the window were dolls and horses and little carts. For these Joe did not care, but there were also some little violins, some high priced, and some very low, and over these Joe lingered with loving, covetous eyes. There was one little fiddle to which his heart went out, that cost only three shillings and sixpence. Each day, as he passed the shop, he was drawn to it, and stood looking in, and longed daily more ardently than on the previous day for this three-and-sixpenny violin.

One day he was so lost in admiration and on the schemes he framed as to how he might eventually become possessed of the instrument, that he was unconscious of some boys stealing the meat out of the sort of trough on his shoulder in which he carried it about.

This was the climax of his misdeeds—he had been reprimanded for his blunders, delivering the wrong meat at the customers’ doors; for his dilatory ways in going on his errands. The butcher could endure him no more, and sent him home to his father, who thrashed him, as his welcome.

But he carried home with him the haunting recollections of that beautiful little red fiddle, with its fine black keys. The bow, he remembered, was strung with white horsehair. Joe had now a fixed ambition—something to live for. He would be perfectly happy if he could have that three-shillings-and-sixpenny fiddle. But how were three shillings and sixpence to be earned?

He confided his difficulty to postman Roger Gale, and Roger Gale said he would consider the matter.

A couple of days after the postman said to Joe—

“Gander, they want a lad to sweep the leaves in the drive at the great house. The squire’s coachman told me, and I mentioned you. You’ll have to do it on Saturday, and be paid sixpence.”

Joe’s face brightened. He went home and told his stepmother.

“For once you are going to be useful,” said Mrs. Lambole. “Very well, you shall sweep the drive; then fivepence will come to us, and you shall have a penny every week to spend in sweetstuff at the post office.”

Joe tried to reckon how long it would be before he could purchase the fiddle, but the calculation was beyond his powers; so he asked the postman, who assured him it would take him forty weeks—that is, about ten months.

Little Joe was not cast down. What was time with such an end in view? Jacob served fourteen years for Rachel, and this was only forty weeks for a fiddle!

Joe was diligent every Saturday sweeping the drive. He was ordered whenever a carriage entered to dive behind the rhododendrons and laurels and disappear. He was of a too ragged and idiotic appearance to show in a gentleman’s grounds.

Once or twice he encountered the squire and stood quaking, with his fingers spread out, his mouth and eyes open, and the broom at his feet. The squire spoke kindly to him, but Joe Gander was too frightened to reply.

“Poor fellow,” said the squire to the gardener. “I suppose it is a charity to employ him, but I must say I should have preferred someone else with his wits about him. I will see to having him sent to an asylum for idiots in which I have some interest. There’s no knowing,” said the squire, “no knowing but that with wholesome food, cleanliness, and kindness his feeble mind may be got to understand that two and two make four, which I learn he has not yet mastered.”

Every Saturday evening Joe Gander brought his sixpence home to his stepmother. The woman was not so regular in allowing him his penny out.

“Your edication costs such a lot of money,” she said.

“Steppy, need I go to school any more?” He never could frame his mouth to call her mother.

“Of course you must. You haven’t passed your standard.”

“But I don’t think that I ever shall.”

“Then,” said Mrs. Lambole, “what masses of good food you do eat. You’re perfectly insatiable. You cost us more than it would to keep a cow.”

“Oh, steppy, I won’t eat so much if I may have my penny!”

“Very well. Eating such a lot does no one good. If you will be content with one slice of bread for breakfast instead of two, and the same for supper, you shall have your penny. If you are so very hungry you can always get a swede or a mangold out of Farmer Eggins’s field. Swedes and mangolds are cooling to the blood and sit light on the stomick,” said Mrs. Lambole.

So the compact was made; but it nearly killed Joe. His cheeks and chest fell in deeper and deeper, and his stomach protruded more than ever. His legs seemed hardly able to support him, and his great pale blue wandering eyes appeared ready to start out of his head like the horns of a snail. As for his voice, it was thin and toneless, like the notes on his improvised fiddle, on which he played incessantly.

“The child will always be a discredit to us,” said Lambole. “He don’t look like a human child. He don’t think and feel like a Christian. The shovelfuls of dung he might have brought to cover our garden if he had only given his heart to it!”

“I’ve heard of changelings,” said Mrs. Lambole; “and with this creetur on our hands I mainly believe the tale. They do say that the pixies steal away the babies of Christian folk, and put their own bantlings in their stead. The only way to find out is to heat a poker red-hot and ram it down the throat of the child; and when you do that the door opens, and in comes the pixy mother and runs off with her own child, and leaves your proper babe behind. That’s what we ought to ha’ done wi’ Joe.”

“I doubt, wife, the law wouldn’t have upheld us,” said Lambole, thrusting hot coals back on to the hearth with his foot.

“I don’t suppose it would,” said Mrs. Lambole. “And yet we call this a land of liberty! Law ain’t made for the poor, but for the rich.”

“It is wickedness,” argued the father. “It is just the same with colts—all wickedness. You must drive it out with the stick.”

And now a great temptation fell on little Gander Joe. The squire and his family were at home, and the daughter of the house, Miss Amory, was musical. Her mother played on the piano and the young lady on the violin. The fashion for ladies to play on this instrument had come in, and Miss Amory had taken lessons from the best masters in town. She played vastly better than poor Roger Gale, and she played to an accompaniment.

Sometimes whilst Joe was sweeping he heard the music; then he stole nearer and nearer to the house, hiding behind rhododendron bushes, and listening with eyes and mouth and nostrils and ears. The music exercised on him an irresistible attraction. He forgot his obligation to work; he forgot the strict orders he had received not to approach the garden-front of the house. The music acted on him like a spell. Occasionally he was roused from his dream by the gardener, who boxed his ears, knocked him over, and bade him get back to his sweeping. Once a servant came out from Miss Amory to tell the ragged little boy not to stand in front of the drawing-room window staring in. On another occasion he was found by Miss Amory crouched behind a rose bush outside her boudoir, listening whilst she practised.

No one supposed that the music drew him. They thought him a fool, and that he had the inquisitiveness of the half-witted to peer in at windows and see the pretty sights within.

He was reprimanded, and threatened with dismissal. The gardener complained to the lad’s father and advised a good hiding, such as Joe should not forget.

“These sort of chaps,” said the gardener, “have no senses like rational beings, except only the feeling, and you must teach them as you feed the Polar bears—with the end of a stick.”

One day Miss Amory, seeing how thin and hollow-eyed the child was, and hearing him cough, brought him out a cup of hot coffee and some bread.

He took it without a word, only pulling off his torn straw hat and throwing it at his feet, exposing the full shock of tow-like hair; then he stared at her out of his great eyes, speechless.

“Joe,” she said, “poor little man, how old are you?”

“Dun’now,” he answered.

“Can you read and write?”

“No.”

“Nor do sums?”

“No.”

“What can you do?”

“Fiddle.”

“Have you got a fiddle?”

“Yes.”

“I should like to see it, and hear you play.”

Next day was Sunday. Little Joe forgot about the day, and forgot that Miss Amory would probably be in church in the morning. She had asked to see his fiddle, so in the morning he took it and went down with it to the park. The church was within the grounds, and he had to pass it. As he went by he heard the roll of the organ and the strains of the choir. He stopped to hearken, then went up the steps of the churchyard, listening. A desire came on him to catch the air on his improvised violin, and he put it to his shoulder and drew his bow across the slender cords. The sound was very faint, so faint as to be drowned by the greater volume of the organ and the choir. Nevertheless he could hear the feeble tones close to his ear, and his heart danced at the pleasure of playing to an accompaniment, like Miss Amory. The choir, the congregation, were singing the Advent hymn to Luther’s tune—

“Great God, what do I see and hear?

The end of things created.”

Little Joe, playing his inaudible instrument, came creeping up the avenue, treading on the fallen yellow lime leaves, passing between the tombstones, drawn on by the solemn, beautiful music. Presently he stood in the porch, then he went on; he was unconscious of everything but the music and the joy of playing with it; he walked on softly into the church without even removing his ragged straw cap, though the squire and the squire’s wife, and the rector and the reverend the Mrs. Rector, and the parish churchwarden and the rector’s churchwarden, and the overseer and the waywarden, and all the farmers and their wives were present. He had forgotten about his broken cap in the delight that made the tears fill his eyes and trickle over his pale cheeks.

Then when with a shock the parson and the churchwardens saw the ragged urchin coming up the nave fiddling, with his hat on, regardless of the sacredness of the place, and above all of the sacredness of the presence of the squire, J.P. and D.L., the rector coughed very loud and looked hard at his churchwarden, Farmer Eggins, who turned red as the sun in a November fog, and rose. At the same instant the people’s churchwarden rose, and both advanced upon Joe Gander from opposite sides of the church.

At the moment that they touched him the organ and the singing ceased; and it was to Joe a sudden wakening from a golden dream to a black and raw reality. He looked up with dazed face first at one man, then at the other: both their faces blazed with equal indignation; both were equally speechless with wrath. They conducted him, each holding an arm, out of the porch and down the avenue. Joe heard indistinctly behind him the droning of the rector’s voice continuing the prayers. He looked back over his shoulder and saw the faces of the school-children straining after him through the open door from their places near it. On reaching the steps—there was a flight of five leading to the road—the people’s churchwarden uttered a loud and disgusted “Ugh!” then with his heavy hand slapped the head of the child towards the parson’s churchwarden, who with his still heavier hand boxed it back again; then the people’s churchwarden gave him a blow which sent him staggering forward, and this was supplemented by a kick from the parson’s churchwarden, which sent Joe Gander spinning down the five steps at once and cast him prostrate into the road, where he fell and crushed his extemporised violin.

Then the churchwardens turned, blew their noses, and re-entered the church, where they sat out the rest of the service, grateful in their hearts that they had been enabled that day to show that their office was no sinecure.

The churchwardens were unaware that in banging and kicking the little boy out of the churchyard and into the road they had flung him so that he fell with his head upon the curbstone of the footpath, which stone was of slate, and sharp. They did not find this out through the prayers, nor through the sermon. But when the whole congregation left the church they were startled to find little Joe Gander insensible, with his head cut, and a pool of blood on the footway. The squire was shocked, as were his wife and daughter, and the churchwardens were in consternation. Fortunately the squire’s stables were near the church, and there was a running fountain there, so that water was procured, and the child revived.

Mrs. Amory had in the meantime hastened home and returned with a roll of diachylon plaster and a pair of small scissors. Strips of the adhesive plaster were applied to the wound, and the boy was soon sufficiently recovered to stand on his feet, when the churchwardens very considerately undertook to march him home. On reaching his cottage the churchwardens described what had taken place, painting the insult offered to the worshippers in the most hideous colours, and representing the accident of the cut as due to the violent resistance offered by the culprit to their ejectment of him. Then each pressed a half-crown into the hand of Mr. Lambole and departed to his dinner.

“Now then, young shaver,” exclaimed the father, “at your pranks again! How often have I told you not to go intruding into a place of worship? Church ain’t for such as you. If you had’nt been punished a bit already, wouldn’t I larrup you neither? Oh, no!”

Little Joe’s head was bad for some days. His cheeks were flushed and his eyes bright, and he talked strangely—he who was usually so silent. What troubled him was the loss of his fiddle; he did not know what had become of it, whether it had been stolen or confiscated. He asked after it, and when at last it was produced, smashed to chips, with the strings torn and hanging loose about it like the cordage of a broken vessel, he cried bitterly. Miss Amory came to the cottage to see him, and finding father and stepmother out, went in and pressed five shillings into his hand. Then he laughed with delight, and clapped his hands, and hid the money away in his pocket, but he said nothing, and Miss Amory went away convinced that the child was half a fool. But little Joe had sense in his head, though his head was different from those of others; he knew that now he had the money wherewith to buy the beautiful fiddle he had seen in the shop window many months before, and to get which he had worked and denied himself food.

When Miss Amory was gone, and his stepmother had not returned, he opened the door of the cottage and stole out. He was afraid of being seen, so he crept along in the hedge, and when he thought anyone was coming he got through a gate or lay down in a ditch, till he was some way on his road to the town. Then he ran till he was tired. He had a bandage round his head, and, as his head was hot, he took the rag off, dipped it in water, and tied it round his head again. Never in his life had his mind been clearer than it was now, for now he had a distinct purpose, and an object easily attainable, before him. He held the money in his hand, and looked at it, and kissed it; then pressed it to his beating heart, then ran on. He lost breath. He could run no more. He sat down in the hedge and gasped. The perspiration was streaming off his face. Then he thought he heard steps coming fast along the road he had run, and as he feared pursuit, he got up and ran on.

He went through the village four miles from home just as the children were leaving school, and when they saw him some of the elder cried out that here was “Gander Joe! quack! quack! Joe the Gander! quack! quack! quack!” and the little ones joined in the banter. The boy ran on, though hot and exhausted, and with his head swimming, to escape their merriment.

He got some way beyond the village when he came to a turnpike. There he felt dizzy, and he timidly asked if he might have a piece of bread. He would pay for it if they would change a shilling. The woman at the ‘pike pitied the pale, hollow-eyed child, and questioned him; but her questions bewildered him, and he feared she would send him home, so that he either answered nothing, or in a way which made her think him distraught. She gave him some bread and water, and watched him going on towards the town till he was out of sight. The day was already declining; it would be dark by the time he reached the town. But he did not think of that. He did not consider where he would sleep, whether he would have strength to return ten miles to his home. He thought only of the beautiful red violin with the yellow bridge hung in the shop window, and offered for three shillings and sixpence. Three-and-sixpence! Why, he had five shillings. He had money to spend on other things beside the fiddle. He had been sadly disappointed about his savings from the weekly sixpence. He had asked for them; he had earned them, not by his work only, but by his abstention from two pieces of bread per diem. When he asked for the money, his stepmother answered that she had put it away in the savings bank. If he had it he would waste it on sweetstuff; if it were hoarded up it would help him on in life when left to shift for himself; and if he died, why it would go towards his burying.

So the child had been disappointed in his calculations, and had worked and starved for nothing. Then came Miss Amory with her present, and he had run away with that, lest his mother should take it from him to put in the savings bank for setting him up in life or for his burying. What cared he for either? All his ambition was to have a fiddle, and a fiddle was to be had for three-and-sixpence.

Joe Gander was tired. He was fain to sit down at intervals on the heaps of stones by the roadside to rest. His shoes were very poor, with soles worn through, so that the stones hurt his feet. At this time of the year the highways were fresh metalled, and as he stumbled over the newly broken stones they cut his soles and his ankles turned. He was footsore and weary in body, but his heart never failed him. Before him shone the red violin with the yellow bridge, and the beautiful bow strung with shining white hair. When he had that all his weariness would pass as a dream; he would hunger no more, cry no more, feel no more sickness or faintness. He would draw the bow over the strings and play with his fingers on the catgut, and the waves of music would thrill and flow, and away on those melodious waves his soul would float far from trouble, far from want, far from tears, into a shining, sunny world of music.

So he picked himself up when he fell, and staggered to his feet from the stones on which he rested, and pressed on.

The sun was setting as he entered the town. He went straight to the shop he so well remembered, and to his inexpressible delight saw still in the window the coveted violin, price three shillings and sixpence.

Then he timidly entered the shop, and with trembling hand held out the money.

“What do you want?”

“It,” said the boy. It. To him the shop held but one article. The dolls, the wooden horses, the tin steam-engines, the bats, the kites, were unconsidered. He had seen and remembered only one thing—the red violin. “It,” said the boy, and pointed.

When little Joe had got the violin he pressed it to his shoulder, and his heart bounded as though it would have burst the pigeon breast. His dull eyes lightened, and into his white sunken cheeks shot a hectic flame. He went forth with his head erect and with firm foot, holding his fiddle to the shoulder and the bow in hand.

He turned his face homeward. Now he would return to father and stepmother, to his little bed at the head of the stairs, to his scanty meals, to the school, to the sweeping of the park drive, and to his stepmother’s scoldings and his father’s beatings. He had his fiddle, and he cared for nothing else.

He waited till he was out of the town before he tried it. Then, when he was on a lonely part of the road, he seated himself in the hedge, under a holly tree covered with scarlet berries, and tried his instrument. Alas! it had hung many years in the shop window, and the catgut was old and the glue had lost its tenacity. One string started; then when he tried to screw up a second, it sprang as well, and then the bridge collapsed and fell. Moreover, the hairs on the bow came out. They were unresined.

Then little Joe’s spirits gave way. He laid the bow and the violin on his knees and began to cry.

As he cried he heard the sound of approaching wheels and the clatter of a horse’s hoofs.

He heard, but he was immersed in sorrow and did not heed and raise his head to see who was coming. Had he done so he would have seen nothing, as his eyes were swimming with tears. Looking out of them he saw only as one sees who opens his eyes when diving.

“Halloa, young shaver! Dang you! What do you mean giving me such a cursed hunt after you as this—you as ain’t worth the trouble, eh?”

The voice was that of his father, who drew up before him. Mr. Lambole had made inquiries when it was discovered that Joe was lost, first at the school, where it was most unlikely he would be found, then at the public-house, at the gardener’s and the gamekeeper’s; then he had looked down the well and then up the chimney. After that he went to the cottage in the quarry. Roger Gale knew nothing of him. Presently someone coming from the nearest village mentioned that he had been seen there; whereupon Lambole borrowed Farmer Eggins’s trap and went after him, peering right and left of the road with his one eye.

Sure enough he had been through the village. He had passed the turnpike. The woman there described him accurately as “a sort of a tottle” (fool).

Mr. Lambole was not a pleasant-looking man; he was as solidly built as a navvy. The backs of his hands were hairy, and his fist was so hard, and his blows so weighty, that for sport he was wont to knock down and kill at a blow the oxen sent to Butcher Robbins for slaughter, and that he did with his fist alone, hitting the animal on the head between the horns, a little forward of the horns. That was a great feat of strength, and Lambole was proud of it. He had a long back and short legs. The back was not pliable or bending; it was hard, braced with sinews tough as hawsers, and supported a pair of shoulders that could sustain the weight of an ox.

His face was of a coppery colour, caused by exposure to the air and drinking. His hair was light: that was almost the only feature his son had derived from him. It was very light, too light for his dark red face. It grew about his neck and under his chin as a Newgate collar; there was a great deal of it, and his face, encircled by the pale hair, looked like an angry moon surrounded by a fog bow.

Mr. Lambole had a queer temper. He bottled up his anger, but when it blew the cork out it spurted over and splashed all his home; it flew in the faces and soused everyone who came near him.

Mr. Lambole took his son roughly by the arm and lifted him into the tax cart. The boy offered no resistance. His spirit was broken, his hopes extinguished. For months he had yearned for the red fiddle, price three-and-six, and now that, after great pains and privations, he had acquired it, the fiddle would not sound.

“Ain’t you ashamed of yourself, giving your dear dada such trouble, eh, Viper?”

Mr. Lambole turned the horse’s head homeward. He had his black patch towards the little Gander, seated in the bottom of the cart, hugging his wrecked violin. When Mr. Lambole spoke he turned his face round to bring the active eye to bear on the shrinking, crouching little figure below.

The Viper made no answer, but looked up. Mr. Lambole turned his face away, and the seeing eye watched the horse’s ears, and the black patch was towards a frightened, piteous, pleading little face, looking up, with the light of the evening sky irradiating it, showing how wan it was, how hollow were the cheeks, how sunken the eyes, how sharp the little pinched nose. The boy put up his arm, that held the bow, and wiped his eyes with his sleeve. In so doing he poked his father in the ribs with the end of the bow.

“Now, then!” exclaimed Mr. Lambole with an oath, “what darn’d insolence be you up to now, Gorilla?”

If he had not held the whip in one hand and the reins in the other he would have taken the bow from the child and flung it into the road. He contented himself with rapping Joe’s head with the end of the whip.

“What’s that you’ve got there, eh?” he asked.

The child replied timidly: “Please, father, a fiddle.”

“Where did you get ‘un—steal it, eh?”

Joe answered, trembling: “No, dada, I bought it.”

“Bought it! Where did you get the money?”

“Miss Amory gave it me.”

“How much?”

The Gander answered: “Her gave me five shilling.”

“Five shillings! And what did that blessed” (he did not say “blessed,” but something quite the reverse) “fiddle cost you?”

“Three-and-sixpence.”

“So you’ve only one-and-six left?”

“I’ve none, dada.”

“Why not?”

“Because I spent one shilling on a pipe for you, and sixpence on a thimble for stepmother as a present,” answered the child, with a flicker of hope in his dim eyes that this would propitiate his father.

“Dash me,” roared the roadmaker, “if you ain’t worse nor Mr. Chamberlain, as would rob us of the cheap loaf! What in the name of Thunder and Bones do you mean squandering the precious money over fooleries like that for? I’ve got my pipe, black as your back shall be before to-morrow, and mother has an old thimble as full o’ holes as I’ll make your skin before the night is much older. Wait till we get home, and I’ll make pretty music out of that there fiddle! just you see if I don’t.”

Joe shivered in his seat, and his head fell.

Mr. Lambole had a playful wit. He beguiled his journey home by indulging in it, and his humour flashed above the head of the child like summer lightning. “You’re hardly expecting the abundance of the supper that’s awaiting you,” he said, with his black patch glowering down at the irresponsive heap in the corner of the cart. “No stinting of the dressing, I can tell you. You like your meat well basted, don’t you? The basting shall not incur your disapproval as insufficient. Underdone? Oh, dear, no! Nothing underdone for me. Pickles? I can promise you that there is something in pickle for you, hot—very hot and stinging. Plenty of capers—mutton and capers. Mashed potatoes? Was the request for that on the tip of your tongue? Sorry I can give you only half what you want—the mash, not the potatoes. There is nothing comparable in my mind to young pig with crackling. The hide is well striped, cut in lines from the neck to the tail. I think we’ll have crackling on our pig before morning.”

He now threw his seeing eye into the depths of the cart, to note the effect his fun had on the child, but he was disappointed. It had evoked no hilarity. Joe had fallen asleep, exhausted by his walk, worn out with disappointments, with his head on his fiddle, that lay on his knees. The jogging of the cart, the attitude, affected his wound; the plaster had given way, and the blood was running over the little red fiddle and dripping into its hollow body through the S-hole on each side.

It was too dark for Mr. Lambole to notice this. He set his lips. His self-esteem was hurt at the child not relishing his waggery.

Mrs. Lambole observed it when, shortly after, the cart drew up at the cottage and she lifted the sleeping child out.

“I must take the cart back to Farmer Eggins,” said her husband; “duty fust, and pleasure after.”

When his father was gone Mrs. Lambole said, “Now then, Joe, you’ve been a very wicked, bad boy, and God will never forgive you for the naughtiness you have committed and the trouble to which you have put your poor father and me.” She would have spoken more sharply but that his head needed her care and the sight of the blood disarmed her. Moreover, she knew that her husband would not pass over what had occurred with a reprimand. “Get off your clothes and go to bed, Joe,” she said when she had readjusted the plaster. “You may take a piece of dry bread with you, and I’ll see if I can’t persuade your father to put off whipping of you for a day or two.”

Joe began to cry.

“There,” she said, “don’t cry. When wicked children do wicked things they must suffer for them. It is the law of nature. And,” she went on, “you ought to be that ashamed of yourself that you’d be glad for the earth to open under you and swallow you up like Korah, Dathan, and Abiram. Running away from so good and happy a home and such tender parents! But I reckon you be lost to natural affection as you be to reason.”

“May I take my fiddle with me?” asked the boy.

“Oh, take your fiddle if you like,” answered his mother. “Much good may it do you. Here, it is all smeared wi’ blood. Let me wipe it first, or you’ll mess the bedclothes with it. There,” she said as she gave him the broken instrument. “Say your prayers and go to sleep; though I reckon your prayers will never reach to heaven, coming out of such a wicked unnatural heart.”

So the little Gander went to his bed. The cottage had but one bedroom and a landing above the steep and narrow flight of steps that led to it from the kitchen. On this landing was a small truckle bed, on which Joe slept. He took off his clothes and stood in his little short shirt of very coarse white linen. He knelt down and said his prayers, with both his hands spread over his fiddle. Then he got into bed, and until his stepmother fetched away the benzoline lamp he examined the instrument. He saw that the bridge might be set up again with a little glue, and that fresh catgut strings might be supplied. He would take his fiddle next day to Roger Gale and ask him to help to mend it for him. He was sure Roger would take an interest in it. Roger had been mysterious of late, hinting that the time was coming when Joey would have a first-rate instrument and learn to play like a Paganini. Yes; the case of the red fiddle was not desperate.

Just then he heard the door below open, and his father’s step.

“Where is the toad?” said Mr. Lambole.

Joe held his breath, and his blood ran cold. He could hear every word, every sound in the room below.

“He’s gone to bed,” answered Mrs. Lambole. “Leave the poor little creetur alone to-night, Samuel; his head has been bad, and he don’t look well. He’s overdone.”

“Susan,” said the roadmaker, “I’ve been simmering all the way to town, and bubbling and boiling all the way back, and busting is what I be now, and bust I will.”

Little Joe sat up in bed, hugging the violin, and his tow-like hair stood up on his head. His great stupid eyes stared wide with fear; in the dark the iris in each had grown big, and deep, and solemn.

“Give me my stick,” said Mr. Lambole. “I’ve promised him a taste of it, and a taste won’t suffice to-night; he must have a gorge of it.”

“I’ve put it away,” said Mrs. Lambole. “Samuel, right is right, and I’m not one to stand between the child and what he deserves, but he ain’t in condition for it to-night. He wants feeding up to it.”

Without wasting another word on her the roadmaker went upstairs.

The shuddering, cowering little fellow saw first the red face, surrounded by a halo of pale hair, rise above the floor, then the strong square shoulders, then the clenched hands, and then his father stood before him, revealed down to his thick boots. The child crept back in the bed against the wall, and would have disappeared through it had the wall been soft-hearted, as in fairy tales, and opened to receive him. He clasped his little violin tight to his heart, and then the blood that had fallen into it trickled out and ran down his shirt, staining it—upon the bedclothes, staining them. But the father did not see this. He was effervescing with fury. His pulses went at a gallop, and his great fists clutched spasmodically.

“You Judas Iscariot, come here!” he shouted.

But the child only pressed closer against the wall.

“What! disobedient and daring? Do you hear? Come to me!”

The trembling child pointed to a pretty little pipe on the bedclothes. He had drawn it from his pocket and taken the paper off it, and laid it there, and stuck the silver-headed thimble in the bowl for his stepmother when she came upstairs to take the lamp.

“Come here, vagabond!”

He could not; he had not the courage nor the strength.

He still pointed pleadingly to the little presents he had bought with his eighteenpence.

“You won’t, you dogged, insulting being?” roared the roadmaker, and rushed at him, knocking over the pipe, which fell and broke on the floor, and trampling flat the thimble. “You won’t yet? Always full of sulks and defiance! Oh, you ungrateful one, you!” Then he had him by the collar of his night-shirt and dragged him from his bed, and with his violence tore the button off, and with his other hand he wrenched the violin away and beat the child over the back with it as he dragged him from the bed.

“Oh, my mammy! my mammy!” cried Joe.

He was not crying out for his stepmother. It was the agonised cry of his frightened heart for the one only being who had ever loved him, and whom God had removed from him.

Suddenly Samuel Lambole started back.

Before him, and between him and the child, stood a pale, ghostly form, and he knew his first wife.

He stood speechless and quaking. Then, gradually recovering himself, he stumbled down the stairs, and seated himself, looking pasty and scared, by the fire below.

“What is the matter with you, Samuel?” asked his wife.

“I’ve seen her,” he gasped. “Don’t ask no more questions.”

Now when he was gone, little Joe, filled with terror—not at the apparition, which he had not seen, for his eyes were too dazed to behold it, but with apprehension of the chastisement that awaited him, scrambled out of the window and dropped on the pigsty roof, and from thence jumped to the ground.

Then he ran—ran as fast as his legs could carry him, still hugging his instrument—to the churchyard; and on reaching that he threw himself on his mother’s grave and sobbed: “Oh, mammy, mammy! father wants to beat me and take away my beautiful violin—but oh, mammy! my violin won’t play.”

And when he had spoken, from out the grave rose the form of his lost mother, and looked kindly on him.

Joe saw her, and he had no fear.

“Mammy!” said he, “mammy, my violin cost three shillings and sixpence, and I can’t make it play no-ways.”

“Mammy!” said he, “mammy, my violin cost three shillings and sixpence, and I can’t make it play no-ways.”

Then the spirit of his mother passed a hand over the the strings, and smiled. Joe looked into her eyes, and they were as stars. And he put the violin under his chin, and drew the bow across the strings—and lo! they sounded wondrously. His soul thrilled, his heart bounded, his dull eye brightened. He was as though caught up in a chariot of fire and carried to heavenly places. His bow worked rapidly, such strains poured from the little instrument as he had never heard before. It was to him as though heaven opened, and he heard the angels performing there, and he with his fiddle was taking a part in the mighty symphony. He felt not the cold, the night was not dark to him. His head no longer ached. It was as though after long seeking through life he had gained an undreamed-of prize, reached some glorious consummation.

There was a musical party that same evening at the Hall. Miss Amory played beautifully, with extraordinary feeling and execution, both with and without accompaniment on the piano. Several ladies and gentlemen sang and played; there were duets and trios.

During the performances the guests talked to each other in low tones about various topics.

Said one lady to Mrs. Amory: “How strange it is that among the English lower classes there is no love of music.”

“There is none at all,” answered Mrs. Amory; “our rector’s wife has given herself great trouble to get up parochial entertainments, but we find that nothing takes with the people but comic songs, and these, instead of elevating, vulgarise them.”

“They have no music in them. The only people with music in their souls are the Germans and the Italians.”

“Yes,” said Mrs. Amory with a sigh; “it is sad, but true: there is neither poetry, nor picturesqueness, nor music among the English peasantry.”

“You have never heard of one, self-taught, with a real love of music in this country?”

“Never: such do not exist among us.”

The parish churchwarden was walking along the road on his way to his farmhouse, and the road passed under the churchyard wall.

As he walked along the way—with a not too steady step, for he was returning from the public-house—he was surprised and frightened to hear music proceed from among the graves.

It was too dark for him to see any figure then, only the tombstones loomed on him in ghostly shapes. He began to quake, and finally turned and ran, nor did he slacken his pace till he reached the tavern, where he burst in shouting: “There’s ghosts abroad. I’ve heard ’em in the churchyard making music.”

The revellers rose from their cups.

“Shall we go and hear?” they asked.

“I’ll go for one,” said a man; “if others will go with me.”

“Ay,” said a third, “and if the ghosts be playing a jolly good tune, we’ll chip in.”

So the whole half-tipsy party reeled along the road, talking very loud, to encourage themselves and the others, till they approached the church, the spire of which stood up dark against the night sky.

“There’s no lights in the windows,” said one.

“No,” observed the churchwarden, “I didn’t notice any myself; it was from the graves the music came, as if all the dead was squeakin’ like pigs.”

“Hush!” All kept silence—not a sound could be heard.

“I’m sure I heard music afore,” said the churchwarden. “I’ll bet a gallon of ale I did.”

“There ain’t no music now, though,” remarked one of the men.

“Nor more there ain’t,” said others.

“Well, I don’t care—I say I heard it,” asseverated the churchwarden. “Let’s go up closer.”

All of the party drew nearer to the wall of the graveyard. One man, incapable of maintaining his legs unaided, sustained himself on the arm of another.

“Well, I do believe, Churchwarden Eggins, as how you have been leading us a wild goose chase!” said a fellow.

Then the clouds broke, and a bright, dazzling pure ray shot down on a grave in the churchyard, and revealed a little figure lying on it.

“I do believe,” said one man, “as how, if he ain’t led us a goose chase, he’s brought us after a Gander—surely that is little Joe.”

Thus encouraged, and their fears dispelled, the whole half-tipsy party stumbled up the graveyard steps, staggered among the tombs, some tripping on the mounds and falling prostrate. All laughed, talked, joked with one another.

The only one silent there was little Joe Gander—and he was gone to join in the great symphony above.

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)