The “Bold Venture” by Sabine Baring-Gould

The “Bold Venture” is a short story by Sabine Baring-Gould.

The story was first published in The Graphic and was later reprinted in Baring-Gould’s short story collection A Book of Ghosts (1904)

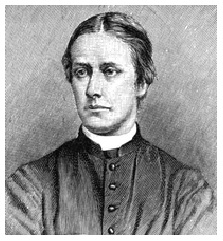

About Sabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924) was an English writer and scholar. He was also an Anglican Priest.

Although he is probably best remembered for writing the hymns Onward Christian Soldiers and Now the Day is Over, Baring-Gould was a prolific writer whose bibliography consists of over 1,200 publications, including The Book of Werewolves (non-fiction).

The “Bold Venture” by Sabine Baring-Gould

(Unabridged Online Text)

The little fisher-town of Portstephen comprised two strings of houses facing each other at the bottom of a narrow valley, down which the merest trickle of a stream decanted into the harbour. The street was so narrow that it was at intervals alone that sufficient space was accorded for two wheeled vehicles to pass one another, and the road-way was for the most part so narrow that each house door was set back in the depth of the wall, to permit the foot-passenger to step into the recess to avoid being overrun by the wheels of a cart that ascended or descended the street.

The inhabitants lived upon the sea and its produce. Such as were not fishers were mariners, and but a small percentage remained that were neither—the butcher, the baker, the smith, and the doctor; and these also lived by the sea, for they lived upon the sailors and fishermen.

For the most part, the seafaring men were furnished with large families. The net in which they drew children was almost as well filled as the seine in which they trapped pilchards.

Jonas Rea, however, was an exception; he had been married for ten years, and had but one child, and that a son.

“You’ve a very poor haul, Jonas,” said to him his neighbour, Samuel Carnsew; “I’ve been married so long as you and I’ve twelve. My wife has had twins twice.”

“It’s not a poor haul for me, Samuel,” replied Jonas, “I may have but one child, but he’s a buster.”

Jonas had a mother alive, known as Old Betty Rea. When he married, he had proposed that his mother, who was a widow, should live with him. But man proposes and woman disposes. The arrangement did not commend itself to the views of Mrs. Rea, junior—that is to say, of Jane, Jonas’s wife.

Betty had always been a managing woman. She had managed her house, her children, and her husband; but she speedily was made aware that her daughter-in-law refused to be managed by her.

Jane was, in her way, also a managing woman: she kept her house clean, her husband’s clothes in order, her child neat, and herself the very pink of tidiness. She was a somewhat hard woman, much given to grumbling and finding fault.

Jane and her mother-in-law did not come to an open and flagrant quarrel, but the fret between them waxed intolerable; and the curtain-lectures, of which the text and topic was Old Betty, were so frequent and so protracted that Jonas convinced himself that there was smoother water in the worst sea than in his own house.

He was constrained to break to his mother the unpleasant information that she must go elsewhere; but he softened the blow by informing her that he had secured for her residence a tiny cottage up an alley, that consisted of two rooms only, one a kitchen, above that a bedchamber.

The old woman received the communication without annoyance. She rose to the offer, for she had also herself considered that the situation had become unendurable. Accordingly, with goodwill, she removed to her new quarters, and soon made the house look keen and cosy.

But, so soon as Jane gave indications of becoming a mother, it was agreed that Betty should attend on her daughter-in-law. To this Jane consented. After all, Betty could not be worse than another woman, a stranger.

And when Jane was in bed, and unable to quit it, then Betty once more reigned supreme in the house and managed everything—even her daughter-in-law.

But the time of Jane’s lying upstairs was brief, and at the earliest possible moment she reappeared in the kitchen, pale indeed and weak, but resolute, and with firm hand withdrew the reins from the grasp of Betty.

In leaving her son’s house, the only thing that Betty regretted was the baby. To that she had taken a mighty affection, and she did not quit till she had poured forth into the deaf ear of Jane a thousand instructions as to how the babe was to be fed, clothed, and reared.

As a devoted son, Jonas never returned from sea without visiting his mother, and when on shore saw her every day. He sat with her by the hour, told her of all that concerned him—except about his wife—and communicated to her all his hopes and wishes. The babe, whose name was Peter, was a topic on which neither wearied of talking or of listening; and often did Jonas bring the child over to be kissed and admired by his grandmother.

Jane raised objections—the weather was cold and the child would take a chill; grandmother was inconsiderate, and upset its stomach with sweetstuff; it had not a tidy dress in which to be seen: but Jonas overruled all her objections. He was a mild and yielding man, but on this one point he was inflexible—his child should grow up to know, love, and reverence his mother as sincerely as did he himself. And these were delightful hours to the old woman, when she could have the infant on her lap, croon to it, and talk to it all the delightful nonsense that flows from the lips of a woman when caressing a child.

Moreover, when the boy was not there, Betty was knitting socks or contriving pin-cases, or making little garments for him; and all the small savings she could gather from the allowance made by her son, and from the sale of some of her needlework, were devoted to the same grandchild.

As the little fellow found his feet and was allowed to toddle, he often wanted to “go to granny,” not much to the approval of Mrs. Jane. And, later, when he went to school, he found his way to her cottage before he returned home so soon as his work hours in class were over. He very early developed a love for the sea and ships.

This did not accord with Mrs. Jane’s ideas; she came of a family that had ever been on the land, and she disapproved of the sea. “But,” remonstrated her husband, “he is my son, and I and my father and grandfather were all of us sea-dogs, so that, naturally, my part in the boy takes to the water.”

And now an idea entered the head of Old Betty. She resolved on making a ship for Peter. She provided herself with a stout piece of deal [fir or pine wood] of suitable size and shape, and proceeded to fashion it into the form of a cutter, and to scoop out the interior. At this Peter assisted. After school hours he was with his grandmother watching the process, giving his opinion as to shape, and how the boat was to be rigged and furnished. The aged woman had but an old knife, no proper carpentering tools, consequently the progress made w

as slow. Moreover, she worked at the ship only when Peter was by. The interest excited in the child by the process was an attraction to her house, and it served to keep him there. Further, when he was at home, he was being incessantly scolded by his mother, and the preference he developed for granny’s cottage caused many a pang of jealousy in Jane’s heart.

Peter was now nine years old, and remained the only child, when a sad thing happened. One evening, when the little ship was rigged and almost complete, after leaving his grandmother, Peter went down to the port. There happened to be no one about, and in craning over the quay to look into his father’s boat, he overbalanced, fell in, and was drowned.

The grandmother supposed that the boy had returned home, the mother that he was with his grandmother, and a couple of hours passed before search for him was instituted, and the body was brought home an hour after that. Mrs. Jane’s grief at losing her child was united with resentment against Old Betty for having drawn the child away from home, and against her husband for having encouraged it. She poured forth the vials of her wrath upon Jonas. He it was who had done his utmost to have the boy killed, because he had allowed him to wander at large, and had provided him with an excuse by allowing him to tarry with Old Betty after leaving school, so that no one knew where he was. Had Jonas been a reasonable man, and a docile husband, he would have insisted on Peter returning promptly home every day, in which case this disaster would not have occurred. “But,” said Jane bitterly, “you never have considered my feelings, and I believe you did not love Peter, and wanted to be rid of him.”

The blow to Betty was terrible; her heart-strings were wrapped about the little fellow; and his loss was to her the eclipse of all light, the death of all her happiness.

When Peter was in his coffin, then the old woman went to the house, carrying the little ship. It was now complete with sails and rigging.

“Jane,” said she, “I want thickey ship to be put in with Peter. ‘Twere made for he, and I can’t let another have it, and I can’t keep it myself.”

“Nonsense,” retorted Mrs. Rea, junior. “The boat can be no use to he, now.”

“I wouldn’t say that. There’s naught revealed on them matters. But I’m cruel certain that up aloft there’ll be a rumpus if Peter wakes up and don’t find his ship.”

“You may take it away; I’ll have none of it,” said Jane.

So the old woman departed, but was not disposed to accept discomfiture. She went to the undertaker.

“Mr. Matthews, I want you to put this here boat in wi’ my gran’child Peter. It will go in fitty at his feet.”

“Very sorry, ma’am, but not unless I break off the bowsprit. You see the coffin is too narrow.”

“Then put’n in sideways and longways.”

“Very sorry, ma’am, but the mast is in the way. I’d be forced to break that so as to get the lid down.”

Disconcerted, the old woman retired; she would not suffer Peter’s boat to be maltreated.

On the occasion of the funeral, the grandmother appeared as one of the principal mourners. For certain reasons, Mrs. Jane did not attend at the church and grave.

As the procession left the house, Old Betty took her place beside her son, and carried the boat in her hand. At the close of the service at the grave, she said to the sexton: “I’ll trouble you, John Hext, to put this here little ship right o’ top o’ his coffin. I made’n for Peter, and Peter’ll expect to have’n.” This was done, and not a step from the grave would the grandmother take till the first shovelfuls had fallen on the coffin and had partially buried the white ship.

When Granny Rea returned to her cottage, the fire was out. She seated herself beside the dead hearth, with hands folded and the tears coursing down her withered cheeks. Her heart was as dead and dreary as that hearth. She had now no object in life, and she murmured a prayer that the Lord might please to take her, that she might see her Peter sailing his boat in paradise.

Her prayer was interrupted by the entry of Jonas, who shouted: “Mother, we want your help again. There’s Jane took bad; wi’ the worrit and the sorrow it’s come on a bit earlier than she reckoned, and you’re to come along as quick as you can. ‘Tisn’t the Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away, but topsy-turvy, the Lord hath taken away and is givin’ again.”

Betty rose at once, and went to the house with her son, and again—as nine years previously—for a while she assumed the management of the house; and when a baby arrived, another boy, she managed that as well.

The reign of Betty in the house of Jonas and Jane was not for long. The mother was soon downstairs, and with her reappearance came the departure of the grandmother.

And now began once more the same old life as had been initiated nine years previously. The child carried to its grandmother, who dandled it, crooned and talked to it. Then, as it grew, it was supplied with socks and garments knitted and cut out and put together by Betty; there ensued the visits of the toddling child, and the remonstrances of the mother. School time arrived, and with it a break in the journey to or from school at granny’s house, to partake of bread and jam, hear stories, and, finally, to assist at the making of a new ship.

If, with increase of years, Betty’s powers had begun to fail, there had been no corresponding decrease in energy of will. Her eyes were not so clear as of old, nor her hearing so acute, but her hand was not unsteady. She would this time make and rig a schooner and not a cutter.

Experience had made her more able, and she aspired to accomplish a greater task than she had previously undertaken. It was really remarkable how the old course was resumed almost in every particular. But the new grandson was called Jonas, like his father, and Old Betty loved him, if possible, with a more intense love than had been given to the first child. He closely resembled his father, and to her it was a renewal of her life long ago, when she nursed and cared for the first Jonas. And, if possible, Jane became more jealous of the aged woman, who was drawing to her so large a portion of her child’s affection. The schooner was nearly complete. It was somewhat rude, having been worked with no better tool than a penknife, and its masts being made of knitting-pins.

On the day before little Jonas’s ninth birthday, Betty carried the ship to the painter.

“Mr. Elway,” said she, “there be one thing I do want your help in. I cannot put the name on the vessel. I can’t fashion the letters, and I want you to do it for me.”

“All right, ma’am. What name?”

“Well, now,” said she, “my husband, the father of Jonas, and the grandfather of the little Jonas, he always sailed in a schooner, and the ship was the Bold Venture.”

“The Bonaventura, I think. I remember her.”

“I’m sure she was the Bold Venture.”

“I think not, Mrs. Rea.”

“It must have been the Bold Venture or Bold Adventurer. What sense is there in such a name as Boneventure? I never heard of no such venture, unless it were that of Jack Smithson, who jumped out of a garret window, and sure enough he broke a bone of his leg. No, Mr. Elway, I’ll have her entitled the Bold Venture.”

“I’ll not gainsay you. Bold Venture she shall be.”

Then the painter very dexterously and daintily put the name in black paint on the white strip at the stern.

“Will it be dry by to-morrow?” asked the old woman. “That’s the little lad’s birthday, and I promised to have his schooner ready for him to sail her then.”

“I’ve put dryers in the paint,” answered Mr. Elway, “and you may reckon it will be right for to-morrow.”

That night Betty was unable to sleep, so eager was she for the day when the little boy would attain his ninth year and become the possessor of the beautiful ship she had fashioned for him with her own hands, and on which, in fact, she had been engaged for more than a twelvemonth.

Nor was she able to eat her simple breakfast and noonday meal, so thrilled was her old heart with love for the child and expectation of his delight when the Bold Venture was made over to him as his own.

She heard his little feet on the cobblestones of the alley: he came on, dancing, jumping, fidgeted at the lock, threw the door open and burst in with a shout—

“See! see, granny! my new ship! Mother has give it me. A real frigate—with three masts, all red and green, and cost her seven shillings at Camelot Fair yesterday.” He bore aloft a very magnificent toy ship. It had pennants at the mast-top and a flag at stern. “Granny! look! look! ain’t she a beauty? Now I shan’t want your drashy old schooner when I have my grand new frigate.”

“Won’t you have your ship—the Bold Venture?”

“No, granny; chuck it away. It’s a shabby bit o’ rubbish, mother says; and see! there’s a brass cannon, a real cannon that will go off with a bang, on my frigate. Ain’t it a beauty?”

“Oh, Jonas! look at the Bold Venture!”

“No, granny, I can’t stay. I want to be off and swim my beautiful seven-shilling ship.”

Then he dashed away as boisterous as he had dashed in, and forgot to shut the door. It was evening when the elder Jonas returned home, and he was welcomed by his son with exclamations of delight, and was shown the new ship.

“But, daddy, her won’t sail; over her will flop in the water.”

“There is no lead on the keel,” remarked the father. “The vessel is built for show only.”

Then he walked away to his mother’s cottage. He was vexed. He knew that his wife had bought the toy with the deliberate intent of disappointing and wounding her mother-in-law; and he was afraid that he would find the old lady deeply mortified and incensed. As he entered the dingy lane, he noticed that her door was partly open.

The aged woman was on the seat by the table at the window, lying forward clasping the ship, and the two masts were run through her white hair; her head rested, partly on the new ship and partly on the table.

“Mother!” said he. “Mother!”

There was no answer.

The feeble old heart had given way under the blow, and had ceased to beat.

I was accustomed, a few summers past, to spend a couple of months at Portstephen. Jonas Rea took me often in his boat, either mackerel fishing, or on excursions to the islets off the coast, in quest of wild birds. We became familiar, and I would now and then spend an evening with him in his cottage, and talk about the sea, and the chances of a harbour of refuge being made at Portstephen, and sometimes we spoke of our own family affairs. Thus it was that, little by little, the story of the ship Bold Venture was told me.

Mrs. Jane was no more in the house.

“It’s a curious thing,” said Jonas Rea, “but the first ship my mother made was no sooner done than my boy Peter died, and when she made another, with two masts, as soon as ever it was finished she died herself, and shortly after my wife, Jane, who took a chill at mother’s funeral. It settled on her chest, and she died in a fortnight.”

“Is that the boat?” I inquired, pointing to a glass case on a cupboard, in which was a rudely executed schooner.

“That’s her,” replied Jonas; “and I’d like you to have a look close at her.”

I walked to the cupboard and looked.

“Do you see anything particular?” asked the fisherman.

“I can’t say that I do.”

“Look at her masthead. What is there?”

After a pause I said: “There is a grey hair, that is all, like a pennant.”

“I mean that,” said Jonas. “I can’t say whether my old mother put a hair from her white head there for the purpose, or whether it caught and fixed itself when she fell forward clasping the boat, and the masts and spars and shrouds were all tangled in her hair. Anyhow, there it be, and that’s one reason why I’ve had the Bold Venture put in a glass case—that the white hair may never by no chance get brushed away from it. Now, look again. Do you see nothing more?”

“Can’t say I do.”

“Look at the bows.”

I did so. Presently I remarked: “I see nothing except, perhaps, some bruises, and a little bit of red paint.”

“Ah! that’s it, and where did the red paint come from?”

I was, of course, quite unable to suggest an explanation.

Presently, after Mr. Rea had waited—as if to draw from me the answer he expected—he said: “Well, no, I reckon you can’t tell. It was thus. When mother died, I brought the Bold Venture here and set her where she is now, on the cupboard, and Jonas, he had set the new ship, all red and green, the Saucy Jane it was called, on the bureau. Will you believe me, next morning when I came downstairs the frigate was on the floor, and some of her spars broken and all the rigging in a muddle.”

“There was no lead on the bottom. It fell down.”

“It was not once that happened. It came to the same thing every night; and what is more, the Bold Venture began to show signs of having fouled her.”

“How so?”

“Run against her. She had bruises, and had brought away some of the paint of the Saucy Jane. Every morning the frigate, if she were’nt on the floor, were rammed into a corner, and battered as if she’d been in a bad sea.”

“But it is impossible.”

“Of course, lots o’ things is impossible, but they happen all the same.”

“Well, what next?”

“Jane, she was ill, and took wus and wus, and just as she got wus so it took wus as well with the Saucy Jane. And on the night she died, I reckon that there was a reg’lar pitched sea-fight.”

“But not at sea.”

“Well, no; but the frigate seemed to have been rammed, and she was on the floor and split from stem to stern.”

“And, pray, has the Bold Venture made no attempt since? The glass case is not broken.”

“There’s been no occasion. I chucked what remained of the Saucy Jane into the fire.”

Sabine Baring-Gould (1834 — 1924)