Public Domain Text: The Dance by E. F. Benson

“The Dance” is taken from Benson’s Spook Stories anthology, published in 1934. It’s the grim tale of a sadistic individual who loves playing sick games and causing pain to those around him. His devotion to his sport is so strong that even death does not halt his play.

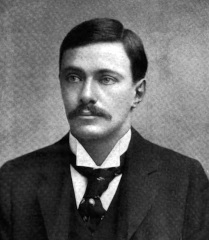

About E. F. Benson

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

The Dance

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

I

Philip Hope had been watching with little neighing giggles of laughter the battle between a spider and a wasp that had been caught in its web. Once or twice the wasp nearly broke free, it hung with one wing only entangled in the tough light threads and he feared it would escape. But its adversary was always too quick and too clever; it swarmed about on its silken ladders, lean and nimble, and, by some process too rapid for Philip to follow, wound a new coil round head or struggling leg.

“Why, it’s noosing its neck I believe,” chuckled Philip, putting on his glasses, “like a hangman at work at eight o’clock in the morning. And it’s got grey tips to its paws, like a hangman’s gloves. Adorable!”

Clever spider! Philip’s sympathy was entirely with it: he backed brains and agility against the buzzing, clumsy creature which had that curved sting, one stroke of which, if it could find its due target in the fat, round, mottled body of the other, would put an end to the combat. And the spider seemed to know that there was death in that horny scimitar so furiously stabbing, and skirted round it, keeping out of striking distance, while it spun its gossamers round the less dangerous members of its prey. The other wing was neatly tied up now, and then suddenly the spider pounced on the thread-like waist that joined the striped body to the thorax, and appeared to tear or to bite it in half.

The body dropped from the web, and the spider made a parcel of the rest, and took it into the woven tunnel at the centre of its home. Never was anything more neat and cruel; and neatness and cruelty were admirable qualities. Philip left the bed of dahlias, where he had watched this enthralling little spectacle, and stood still a moment thinking of some fresh entertainment. In person he was notably small and slight, narrow-chested, with spindle arms and legs. He leaned on a stick as he walked, for one of his knees was permanently stiff, but he was quick and nimble in spite of his limping gait. His clothes were fantastic; he wore a bright mustard-coloured suit, a green silk tie, a pink, silk shirt, with a low collar, above which rose a rather long neck supporting his very small sharp-chinned face, quite hairless and looking as if no razor had ever plied across it. His eyes were steel grey, and had no lashes on either lid: whether they looked up or down, they gave the impression of a mocking and amused vigilance. They saw much and derived much entertainment. He was hatless, and the thick crop of auburn hair that covered his head could deceive nobody, nor indeed did he intend that it should.

Beyond the lawn where he stood, half-screened by a row of shrubs, was the en tout cas court where, half an hour ago, he had left his wife and his secretary, Julian Weston, playing tennis. In point of age he might have been the father of either of them, and their combined years, twenty-two and twenty-three, just equalled his own forty-five. He could not catch any glimpse of their darting white-clad figures through the interstices of the hedge, and he supposed they had finished their game. He had told them that he intended to go for a motor drive, and no doubt they thought that he had gone, but there was no reason why he should not have a peep at them, to see what they were doing; and he walked quietly up to the screening shrubs. There they were, silly fools, only a few yards from him, sitting one on each side of the summer house. Sybil bounced a tennis ball on the tiled floor in the open space between them; Julian caught it and bounced it back. It was worth while to watch them for a little, and see what they would do when they tired of that. Five or six times the ball passed between them and then Julian missed it, and it rolled away, disregarded, under the table in the corner. They sat there, looking at each other. Philip, crouching down, moved a little nearer still invisible to them. He wanted to hear as well as to see. His face, satyr-like with its sharp chin and prominent ears, was alight with some secret merriment, and his small white teeth closed on his lower lip to prevent his laughing outright.

For the last week he had watched those two young creatures falling in love with each other. They had made friends at once when Julian came here a month ago, with the frank attraction of the young for each other: they rode, they played games, they bathed together in light-hearted enjoyment. But very soon Philip had seen that behind this natural comradeship there was stirring something that both troubled and kindled them. Their eyes were alight in each other’s presence, their ears listened for each other. Sometimes each feigned an unconsciousness of the other till some swift glance betrayed the silly pretence. They would soon be as helpless in the silken web that enwrapped them as the wasp he had been watching, and indeed he himself was like the clever spider; for he had certainly helped to spread the net for them, encouraging their comradeship for the very purpose that they should get entangled. All this amused Philip, and it would be amusing to begin petting and making love to his wife again; that would touch both of them up. He would be very neat and dainty in device.

Suddenly these agreeable plans faded from his mind, and he became intensely alert. Julian got up, and Sybil also, and they stood facing each other.

“Does he know? Does he guess, do you think?” he asked.

She gave no audible answer. Then, which of them moved first it was difficult to say, but next moment they were clasped to each other, and then as suddenly stood apart again.

Philip, shaking with laughter, stole quietly away, for he had no notion of disclosing himself; that would spoil it all. Something in the abruptness of what he had seen made him feel certain that they had never passionately kissed like that before; for, if so, they would not have leaped to it thus and then instantly have recoiled from what they had done. But the time was ripe for him to intervene, and he promised himself an amusing week or two. Intensely amusing, too, was Julian’s question as to whether Sybil thought that he knew. Did the boy take him for an idiot?

“I’ll answer that question in my own way,” thought Philip. “It will be great sport.”

It was too late to go for his motor drive now, and, passing through the house, he went for a short stroll along the edge of the sand-cliffs that rose a hundred sheer feet above the sea. He had been married now for three years, having been over forty when first he met Sybil Mannering. At once he had determined that he must possess this golden girl of nineteen. He was not in the least in love with her, but her beauty and her child-like vitality nourished him: it would be delicious to have the right to pet and caress her. She was poor, but he was rich, which was all to the good, for that made an ally of her mother. He made the appeal of the weak to the strong, of the pitiful little loving crétin (so he called himself) to the young Juno, and her compassion had aided his suit. Then, as she got to know him, there grew in her a horror of him, and that was pleasant; her fright and her horror were grand nourishment, for they fed his dainty sadism. He loaded her with jewels, he designed her dresses. He took her about everywhere, boring himself with parties and balls for the sake of seeing the admiration she excited. But when he had had enough he would go to his hostess and say, “Such a charming evening, but Sybil will scold me if we stop any longer.”

Then as they drove home he would say to her, “Loving little wifie, aren’t I good to you, taking you out of the gutter and covering you with pearls? You must be good to me. Give me a kiss,” and he would burst out into his little goat-like laugh at the touch of her cold lips. Then he had tired of that sport, but to-day, as he limped perkily along the cliff-edge, he thought he would renew his caresses. She shuddered at them before, she would shudder now with a far more acute loathing, and Julian would be there to see. Then he must make some needful alterations in his will. The chances were a hundred to one that she would survive him, and though nothing could prevent her from marrying Julian, he must make it as disagreeable as he could; make her feel that he wasn’t quite done with yet. “I wonder if the dead can return,” he thought. “What fun they might have!” He did not in the least contemplate dying for a long while yet, but in case anything happened to him he would get his lawyer to frame a codicil. That, however, was not so important as the neat little comedy that he was planning.

It was growing dark; the revolving beams from the Cromer lighthouse swept across the golf-links like the spokes of a luminous wheel, and shone where he walked and then passed on and scoured the sea. The house he had built here stood within a hundred yards of the cliff-edge, queer and rococo, with two sharp turrets like the pricked ears of some wary animal. A big hall-like sitting room with a gallery above running along the length of it, and communicating with the bedrooms, occupied the most of the ground floor. Out of it opened a small dining room hatched to the kitchen, and close to the front door was Philip’s sitting-room where a tape-machine ticked out Stock Exchange prices and the news of the day. You could scarcely call him a gambler, so acute and so well-reasoned were his conclusions as to the effect of the news of the day on markets, and often he spent the entire evening here, making out what would be the effect of the latest news on the market next day, and selling or buying first thing in the morning.

But to-night he had a more amusing diversion; there was to be dancing. He had the furniture in the hall moved away to the sides of the room and the rugs rolled up, and the polished boards made a very decent floor for one couple. He sat himself by the gramophone with jazz records handy, and watched the two with little squeals of pleasure.

“You beautiful creatures,” he cried. “Why, you’re positively made for each other! Dance again! I’ll find a more exciting tune. Hold her close, Julian. Bend your head down to her a little as if you wanted to kiss her. Forget that there’s old hubby watching you. Look into his eyes, Sybil. Try to think that you’re in love with him.”

He gave his little goat-like laugh.

“Now we’ll have a contrast,” he cried. “You shall dance with me, darling. I can hop round in spite of my poor stiff leg.”

He hugged her close to him, he skipped and capered round her, dragging her after him.

“Faster, more fire!” he cried. “Aren’t I grotesque, and isn’t it fun? I’m sure you never guessed I could be so nimble. Good Lord, how hot it makes one! Wait a second, while I take off my wig.”

He threw it into a chair: his head was as hairless as an egg, and gleamed with sweat.

“Now come along again,” he said. “You are kind to your poor little cripple! Now have another turn with Julian, while I cool down. But give me a kiss first.”

He gave her half a dozen little butterfly kisses, then kissed her on the mouth, cackling with laughter to see her eyes grow stale.

Every day he made traps and tortures for them. One night he went to bed early, passing with his limping tread along the gallery above the hall that led to the bedrooms beyond, knowing that, in spite of his injunction that they should sit up and amuse themselves together, he had poisoned the hour for them. He was right, and it was but a few minutes later that he heard them come upstairs, and Sybil went into her room next door, and Julian’s step passed on.

He went in to see her before long in his yellow silk dressing-gown, and sent her maid away, saying that he would brush her hair for her. He kissed the nape of her neck, he talked to her about Julian, the handsomest boy he had ever seen: did not she think so? But did she think he was well? Sometimes he seemed to have something on his mind.

The next morning it would be Julian’s turn. Philip told him he must be getting married soon. Wasn’t there some nice girl he was fond of? Then he consulted him about Sybil. He thought she had something on her mind. Julian must find out—they were such friends—what was it, and tell him, and whatever it was, it must be put right. Sybil mustn’t worry over any secret disquietude. They would dance again to-night, and dress up for it. What should Julian wear? Could he not make a costume—Sybil and he would help—out of a couple of leopard skins? Julian should be a young Dionysus, and Sybil a Mænad, wearing that Grecian frock that he had designed for her. They would have dinner in the loggia in the walled garden, and dance on the grass, and Julian should chase his Mænad over the lawn through moonlight and shadow. He laughed to see the boy’s eyes gleam and then grown cold with hate. He was on the rack and no wonder, and the levers could be pulled over a little farther yet.

Then he had other devices for a day or two; he never let them be alone together for a moment, to see if that suited them better. He kept Julian at work all morning, he took Sybil out with him all afternoon, and there were prospectuses for his secretary to read and report on when dinner was over. He nagged at Sybil; he made mock of her before the servants, and it was amusing to see the angry blood leap to Julian’s face, and the whiteness come to hers. Rare sport: they would have killed him, he thought, if they had the spirit of a louse between them.

“What happy times we’re having,” he said one day. “We’ll stop on here into October, for we’re such a loving harmonious little party. Do put your mother off, Sybil; she will spoil our lovely little triangle. Yet we’ve both got reason to be grateful to her for bringing us together. What about your marrying Mother Mannering, Julian? It would be nice to have you in the family. She can’t be more than sixty, and as tough as a guinea-fowl without the guineas.”

There they were then: they were bound on wheels for his breaking. He could wrench this one or that as he pleased, and the other could do nothing but look on impotently. For a day or two yet it was pleasant to make sport with them, but the edge was wearing off his enjoyment and it was time to make an end.

He took Julian for a stroll along the cliff one afternoon.

“I’ve got something to say to you, dear fellow,” he said. “I hope it will meet with your approval, not that it matters very much. Now cudgel your clever brains, and see if you can guess what it is.”

“I’ve no idea, sir,” said Julian.

“Dull of you, sir. Not even if I give you three guesses? Well, it’s just this. I’ve had enough of you, and you can take yourself off to-morrow. A week’s wages or a month’s wages of course, whichever is right. My reason? Just that Sybil and I will be so very happy alone. That’s all. What damned idiots you and she have been making of yourselves. So off you go, and there will be a little discipline for her. You must think of us dancing in the evening. So that’s all pleasantly settled.”

He was walking on the very edge of the cliff, and, as he finished speaking, he turned and looked out seawards. A yard behind him there was an irregular zigzag crack in the turf, and now it ran this way and that, spreading and widening. Next moment the riband of earth on which he stood suddenly slipped down a foot or two, and with a shrill cry of fright he jumped for the solid. But the poised lump slid away altogether from him, and all he could do was to clutch with his fingers at the broken edge.

“Quick, get hold of my hands, you senseless ape,” he squealed.

Julian did not move. If he had thrown himself on the ground and grasped at the fingers which clutched the crumbling earth he might perhaps have saved him. But for that crucial second of time his body made no response: if it could have moved at all, it must have leaped and danced at the thought of what would presently befall, and he looked smiling and unwavering into those lashless, panic-stricken eyes. Next moment he was alone on the empty down. He felt no smallest pang of remorse; he told himself that by no possibility could he have saved him. But, soft as the fall of a single snow-flake, fear settled on his heart and then melted.

A flock of sheep were feeding not far away, and they scattered before him as he ran back to the house to get the help which his heart rejoiced to know must be unavailing.

II

The house remained shut up for a year and the turrets pricked their ears in vain to hear the sounds of life returning to it. Philip, by the codicil he had executed the day before his death, had revoked his previous will, and had left to Sybil only certain marriage settlements which he had no power to touch and this house “where” (so ran his phrase) “we are now passing such loving and harmonious days.” During this year Julian’s father had died, and their marriage took place in the autumn.

To-day they came to spend here their month of honeymoon. Fenton, Philip’s butler, and his wife had been living here as caretakers, the garden had been well looked after, and all was exactly as it had been a year ago. But the shadow of the mocking malevolence had passed for ever from it, and the spring sunshine in their hearts was as tranquil as the autumn radiance that lay on the lawns. Everything, flower-beds and winding path and sun-steeped wall, was full of memories from which all bitterness was purged; it was sweet to remember what had been, in a babble of talk.

“And there’s the tennis court,” said he, “with the summer house where we sat—”

“Yes, and bounced a ball to and fro between us—” she interrupted.

“And then I missed it and it rolled away, and we thought no more about it. Then I asked you if you thought he had guessed, and we kissed.”

“Just here we stood,” she said.

“And it was on that day that he began to mock us,” he said. “How he enjoyed it! It made sport for him.”

“I think he must have seen us,” she said. “You could never tell what Philip saw. And he wove webs for us. Look, there’s a wasp caught in a spider’s web. I must let it free. I hate spiders. If ever I have a nightmare it’s always about a spider. Oh, what a pity! The sunlight is fading. There’s a sea fog coming up. How chilly it gets at once! Let’s go indoors. And we won’t talk about those things any more.”

The mist formed rapidly, and before they got in it had spread white and low-lying over the lawn. A fire of logs burned in the hall, and as they sat over them in the fading light, a hundred memories which now they left unspoken, began to move about in their minds, like sparks crawling about the ashes of burnt paper that has flared and seems consumed. There was the cabinet gramophone to which they had danced … there was the chair on to which Philip had thrown his wig; above, running the length of the hall, was the gallery along which his limping footstep had passed when he left them to go early to bed, bidding them stay up and divert themselves. How the sparks crawled about the thin crinkling ash! Presently it would all be consumed, and the past collapse into the grey nothingness of forgotten things.

Outside the mist had grown vastly denser, it beleaguered the house, and nothing was to be seen from the windows except a woolly whiteness. From the sea there came the mournful hooting of fog-horns.

“I like that,” said Sybil. “It makes me feel comfortable. We’re safe, we’re at home, and we don’t want anyone to know where we are, like those lost ships. But pull the curtains, it shuts us in more.”

As Julian rattled the rings across the rod he paused, listening.

“Telephone wasn’t it?” he said.

“It can’t have been,” said she. “Why, it’s standing close by my chair, and I heard nothing. It was the curtain-rings.”

“But there it is again,” said he. “It isn’t from this instrument, it sounds as if it came from the study. I think I’ll go and see. The servants won’t have heard it there.”

“If it’s for me, say I’m in my bath,” said Sybil.

Julian went along the passage to the room that had been Philip’s workroom close to the front door. It was dark now, and, as he fumbled for the switch by the door, the bell sounded again, rather faint, rather thin, as if the fog outside muffled it.

He took off the receiver.

“Hullo!” he said.

There came a little goat-like laugh, just audible, and then a voice.

“Settled in comfortably, dear boy?” it asked. “I’ll look in on you before long.”

“Who’s speaking?” said Julian. He heard his voice crack as he asked.

Silence. Once more he asked and there came no reply.

Julian felt the snowflakes of fear settle on him again. But the notion that had flashed out of the darkness into his mind was surely the wildest nonsense. The laugh, the voice, had for that moment sounded unmistakable, but his sane self knew the absurdity of such an idea. He turned out the light and went back to Sybil.

“The telephone did ring, dear,” he said, “but I couldn’t make out who it was. Somebody is going to look in before long. Not at home, I think.”

The fog cleared during the night before a light wind from the sea, and a crystalline October morning awaited them. Sybil had some household businesses that claimed her attention, and Julian walked along the shore until she was ready to come out. Not half a mile away was the precise spot he wished to visit, namely, that belt of shingle at the base of the cliff where, a little more than a year ago, they had found the shattered body on its back with wide-open eyes. He had dreamed of the place last night; he thought that he came here, and that, as he looked, the shingle began to stir and formed itself into the figure of a man lying there, and the dreamer had watched this odd process with interest, wondering what would come next. Then skin began to grow like swiftly spreading grey lichen over the head, and eyes and mouth moulded themselves on a face that was coming to life again; the eyes turned and looked into his, the mouth moved, and Julian awoke in the grip of nightmare. Even when the night was over and the morning luminous the taste of that terror still lingered, and he had to come to the place and convince himself of the emptiness of his dream. There lay the shingle shining and wet from the recession of the tide, and the wholesome sunlight dwelt on it.

Dusk had already fallen when they got home from a motor-drive that afternoon. As she got out Sybil stepped on the side of her foot and gave a little cry of pain. But it was nothing, she said, just a bit of a wrench, and she hobbled into the house.

As Julian returned from taking the car to the garage he noticed that there was a light in Philip’s room by the front door. Sybil perhaps had gone in there, but, when he entered, he found the room was empty. The fire had been lit, and was beginning to burn up. No doubt the housemaid had thought he meant to use the room, and after lighting the fire had forgotten to turn off the switch.

He went on into the hall. Sybil was not there and she must have gone upstairs to take off her cloak and fur tippet and veil. He sat down to look at the evening paper, got interested in a political article, and heard with only half an ear the opening of the door to the bedroom passage at the end of the gallery that crossed the hall. The floor of it was of polished oak boards, uncarpeted, and he heard her step coming along it, and she limped as she walked. Her ankle still hurts her, he thought, and went on with his reading. He wondered then what had happened to her, for she had crossed the gallery several minutes ago, and she had not yet appeared. He had made no doubt that that limping step was hers.

The door at the end of the hall into the kitchen-quarters opened and she came in. She was still in her cloak and furs.

“So sorry, dear,” she said, “but there was a bit of a domestic upset. Fenton told the housemaid to light the fire in the study, and she came running back, rather hysterical, saying that as she was lighting it she saw a man outside in the dusk looking in at the window, and she was frightened.”

“Perhaps she saw me looking in,” said Julian, “When I came back from the garage I saw there was a light in the room.”

“No doubt that was it. But Fenton and the gardener have gone to have a look round.”

“And the foot?” he asked.

She stripped herself of her wrappings and threw them into a chair.

“Perfectly all right,” she said. “It only lasted a minute.”

Motoring had made Julian sleepy, and when, after tea, Sybil gathered up her things and went upstairs he must have fallen into a doze. He did not appear to himself to have gone to sleep, for there was no change of consciousness or of scene, and he thought he was still looking into the fire, and wondering to himself, with an uneasiness that he would not admit, what that limping footstep had been. He had felt no doubt at the time that it was Sybil’s, but she had not been upstairs, nor did she halt in her walk. And he thought of that nightmare of his about the shingle on which Philip had fallen, and of the voice that he had heard on the telephone, and the familiar laugh, and the promise that the speaker would soon be here. Was he here in some bodiless form? Was he giving token of his unseen presence? Then (in his dream) he reached out for the paper he had been reading to divert his thoughts. As he did so his eye fell on the chair from which Sybil had picked up the cloak and veil and fur tippet she had thrown there, but apparently she had forgotten to take the tippet. Then he looked more closely at it and saw it was a wig.

He woke: there was Fenton standing by him.

“The dressing-bell has gone a quarter of an hour ago, sir,” he said.

Julian looked at the chair beside him. There was nothing there: it was all a dream, but the dream had brought the sweat to his forehead.

“Has it really?” he said. “I must have fallen asleep. Oh, by the way, you went to see if there was anyone hanging about in the garden. Did you find anything?”

“No, sir. All quite quiet,” said Fenton.

Sybil lingered behind in the dining-room after dinner to pour fresh water into the bowl of touzle-headed chrysanthemums that stood on the table, and Julian strolled on into the hall. The furniture was pushed aside from the centre of the room and the rugs rolled up, leaving the floor clear. Sybil had said nothing about that to him, but it would be fun to dance. Presently she followed him.

“Oh, Julian, what a good idea,” she said. “How quick you’ve been. Turn on the gramophone. Why, it’s a year since I have danced. Do you remember?… No, don’t remember: forget it.”

Julian, standing with his back to her, picked out a record. Just as the first gay bars of the tune blared out, Sybil shrieked and shrieked again.

“Something’s holding me,” she cried. “Something’s pressing against me. Something’s laughing. Julian, come to me! Oh, my God, it’s he!”

She was struggling in the grip of some invisible force. With her head craned back away from it, her hands wrestled furiously with the empty air, and, still violently resisting, her feet began to make steps on the floor, now tip-toeing in a straight line, now circling. Julian rushed to her, he felt the shape of the unseen horror, he tore at the head and the shoulders of it, but his hands slipped away as if on slime, and fear sucked his strength from him. Then, as if suddenly released, Sybil dropped to the ground, and he knew that all the hellish forces of the unseen was turned on him.

It played on him like a blast of fire or freezing, and he fled from the room, for that was its will. Down the passage he ran with it on his heels, and out into the moonlit night. He dodged this way and that, he tried to bolt back into the house again but it drove him where it would, past the tennis-court and the bed of dahlias, and out of the garden gate and on to the cliff, where the beams of the lighthouse swept across the downs. There was a flock of sheep which scattered as he rushed in among them. There were a boy and a girl, who, as he fled by them, called to him to beware of the cliff-edge that lay directly in front of him. The pencil of light swept across it now, and as he plunged over the edge he saw the line of ripple breaking on to the shingle a hundred feet below, where, one evening, he and the fisherfolk found the shattered body of Philip staring with lashless eyes into the sky.

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)