Public Domain Text: The Hanging of Alfred Wadham by E. F. Benson

“The Hanging of Alfred Wadham” was first published in Britannia Magazine (Dec 21st, 1928). As the title suggests, it’s a story about a man who gets hung for murder. However, although his life was less than perfect, Alfred Wadham was innocent and later appears to return from the grave to haunt the only man who could have saved his neck. However, the apparition’s identity later comes into question.

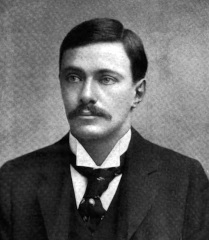

About E. F. Benson

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940) is probably best known for his six Mapp and Lucia books, but he was a very versatile writer who produced a large body of work, including several biographies.

Benson also wrote a number of ghost stories and the author H. P. Lovecraft was impressed enough by Benson’s work to mention him in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature.”

The Hanging of Alfred Wadham

by E. F. Benson

(Unabridged Online Text)

I had been telling Father Denys Hanbury about a very extraordinary séance which I had attended a few days before. The medium in trance had said a whole series of things which were unknown to anybody but myself and a friend of mine who had lately died, and who, so she said, was present and was speaking to me through her. Naturally, from the strictly scientific point of view in which alone we ought to approach such phenomena, such information was not really evidence that the spirit of my friend was in touch with her, for it was already known to me, and might by some process of telepathy have been communicated to the medium from my brain and not through the agency of the dead. She spoke, too, not in her own ordinary voice, but in a voice which certainly was very like his. But his voice was also known to me; it was in my memory even as were the things she had been saying. All this, therefore, as I was remarking to Father Denys, must be ruled out as positive evidence that communications had been coming from the other side of death.

“A telepathic explanation was possible,” I said, “and we have to accept any known explanation which covers the facts before we conclude that the dead have come back into touch with the material world.”

The room was quite warm, but I saw that he shivered slightly and, hitching his chair a little nearer the fire, he spread out his hands to the blaze. Such hands they were: beautiful and expressive of him, and so like the praying hands of Albert Dürer: the blaze shone through them as through rose-red alabaster. He shook his head.

“It’s a terribly dangerous thing to attempt to get into communication with the dead,” he said. “If you seem to get into touch with them you run the risk of establishing connection not with them but with awful and perilous intelligences. Study telepathy by all means, for that is one of the marvels of the mind which we are meant to investigate like any other of the wonderful secrets of Nature. But I interrupt you: you said something else occurred. Tell me about it.”

Now I knew Father Denys’s creed about such things and deplored it. He holds, as his church commands him, that intercourse with the spirits of the dead is impossible, and that when it appears to occur, as it undoubtedly does, the enquirer is really in touch with some species of dramatic demon, who is impersonating the spirit of the dead. Such a thing has always seemed to me as monstrous as it is without foundation, and there is nothing I can discover in the recognized sources of Christian doctrine which justifies such a view.

“Yes: now comes the queer part,” I said. “For, still speaking in the voice of my friend the medium told me something which instantly I believed to be untrue. It could not therefore have been drawn telepathically from me. After that the séance came to an end, and in order to convince myself that this could not have come from him, I looked up the diary of my friend which had been left me at his death, and which had just been sent me by his executors, and was still unpacked. There I found an entry which proved that what the medium had said was absolutely correct. A certain thing—I needn’t go into it—had occurred precisely as she had stated, though I should have been willing to swear to the contrary. That cannot have come into her mind from mine, and there is no source that I can see from which she could have obtained it except from my friend. What do you say to that?”

He shook his head.

“I don’t alter my position at all,” he said. “That information, given it did not come from your mind, which certainly seems to be impossible, came from some discarnate agency. But it didn’t come from the spirit of your friend: it came from some evil and awful intelligence.”

“But isn’t that pure assumption?” I asked. “It is surely much simpler to say that the dead can, under certain conditions, communicate with us. Why drag in the devil?”

He glanced at the clock.

“It’s not very late,” he said. “Unless you want to go to bed, give me your attention for half-an-hour, and I will try to show you.”

The rest of my story is what Father Denys told me, and what happened immediately afterwards.

“Though you are not a Catholic,” he said, “I think you would agree with me about an institution which plays a very large part in our ministry, namely Confession, as regards the sacredness and the inviolability of it. A soul laden with sin comes to his Confessor knowing that he is speaking to one who has the power to pronounce or withhold forgiveness, but who will never, for any conceivable reason, repeat or hint at what has been told him. If there was the slightest chance of the penitent’s confession being made known to anyone, unless he himself, for purposes of expiation or of righting some wrong, chooses to repeat it, no one would ever come to Confession at all. The Church would lose the greatest hold it possesses over the souls of men, and the souls of men would lose that inestimable comfort of knowing (not hoping merely, but knowing) that their sins are forgiven them. Of course the priest may withhold absolution, if he is not convinced that he is dealing with a true penitent, and before he gives it, he will insist that the penitent makes such reparation as is in his power for the wrong he has done. If he has profited by his dishonesty he must make good: whatever crime he has committed he must give warrant that his penitence is sincere. But I think you would agree that in any case the priest cannot, whatever the result of his silence may be, repeat what has been told him. By doing so he might right or avert some hideous wrong, but it is impossible for him to do so. What he has heard, he has heard under the seal of confession, concerning the sacredness of which no argument is conceivable.”

“It is possible to imagine awful consequences resulting from it,” I said. “But I agree.”

“Before now awful consequences have come of it,” he said, “but they don’t touch the principle. And now I am going to tell you of a certain confession that was once made to me.”

“But how can you?” I said. “That’s impossible, surely.”

“For a certain reason, which we shall come to later,” he said, “you will see that secrecy is no longer incumbent on me. But the point of my story is not that: it is to warn you about attempting to establish communication with the dead. Signs and tokens, voices and apparitions appear to come through to us from them, but who sends them? You will see what I mean.”

I settled myself down to listen.

“You will probably not remember with any distinctness, if at all, a murder committed a year ago, when a man called Gerald Selfe met his death. There was no enticing mystery about it, no romantic accessories, and it aroused no public interest. Selfe was a man of loose life, but he held a respectable position, and it would have been disastrous for him if his private irregularities had come to light. For some time before his death he had been receiving blackmailing letters regarding his relations with a certain married woman, and, very properly, he had put the matter into the hands of the police. They had been pursuing certain clues, and on the afternoon before Selfe’s death one of the officers of the Criminal Investigation Department had written to him that everything pointed to his man servant, who certainly knew of his intrigue, being the culprit. This was a young man named Alfred Wadham: he had only lately entered Selfe’s service, and his past history was of the most unsavoury sort. They had baited a trap for him, of which details were given, and suggested that Selfe should display it, which, within an hour or two, he successfully did. This information and these instructions were conveyed in a letter which after Selfe’s death was found in a drawer of his writing-table, of which the lock had been tampered with. Only Wadham and his master slept in his flat; a woman came in every morning to cook breakfast and do the housework, and Selfe lunched and dined at his club, or in the restaurant on the ground floor of this house of flats, and here he dined that night. When the woman came in next morning she found the outer door of the flat open, and Selfe lying dead on the floor of his sitting-room with his throat cut. Wadham had disappeared, but in the slop-pail of his bedroom was water which was stained with human blood. He was caught two days afterwards and at his trial elected to give evidence. His story was that he suspected he had fallen into a trap, and that while Mr. Selfe was at dinner he searched his drawers and found the letter sent by the police, which proved that this was the case. He therefore decided to bolt, and he left the flat that evening before his master came back to it after dinner. Being in the witness-box, he was of course subjected to a searching cross-examination, and contradicted himself in several particulars. Then there was that incriminating evidence in his room, and the motive for the crime was clear enough. After a very long deliberation the jury found him guilty, and he was sentenced to death. His appeal which followed was dismissed.

“Wadham was a Catholic, and since it is my office to minister to Catholic prisoners at the gaol where he was lying under sentence of death, I had many talks with him, and entreated him for the sake of his immortal soul to confess his guilt. But though he was even eager to confess other misdeeds of his, some of which it was ugly to speak of, he maintained his innocence on this charge of murder. Nothing shook him, and though as far as I could judge he was sincerely penitent for other misdeeds, he swore to me that the story he told in court was, in spite of the contradictions in which he had involved himself, essentially true, and that if he was hanged he died unjustly. Up till the last afternoon of his life, when I sat with him for two hours, praying and pleading with him, he stuck to that. Why he should do that, unless indeed he was innocent, when he was eager to search his heart for the confession of other gross wickednesses, was curious; the more I pondered it, the more inexplicable I found it, and during that afternoon doubt as to his guilt began to grow in me. A terrible thought it was, for he had lived in sin and error, and to-morrow his life was to be broken like a snapped stick. I was to be at the prison again before six in the morning, and I still had to determine whether I should give him the Sacrament. If he went to his death guilty of murder, but refusing to confess, I had no right to give it him, but if he was innocent, my withholding of it was as terrible as any miscarriage of justice. Then on my way out I had a word with one of the warders, which brought my doubt closer to me.

“‘What do you make of Wadham?’ I asked.

“He drew aside to let a man pass, who nodded to him: somehow I knew that he was the hangman.

“‘I don’t like to think of it, sir,’ he said. ‘I know he was found guilty, and that his appeal failed. But if you ask me whether I believe him to be a murderer, why no, I don’t.’

“I spent the evening alone: about ten o’clock as I was on the point of going to bed, I was told that a man called Horace Kennion was below, and wanted to see me. He was a Catholic, and though I had been friends with him at one time, certain things had come to my knowledge which made it impossible for me to have anything more to do with him, and I had told him so. He was wicked—oh, don’t misunderstand me; we all do wicked things constantly; the life of us all is a tissue of misdeeds, but he alone of all men I had ever met seemed to me to love wickedness for its own sake. I said I could not see him, but the message came back that his need was urgent, and up he came. He wanted, he told me, to make his confession, not to-morrow, but now, and his Confessor was away. I could not, as a priest, resist that appeal. And his confession was that he had killed Gerald Selfe.

“For a moment I thought this was some impious joke, but he swore he was speaking the truth, and still under the seal of confession gave me a detailed account. He had dined with Selfe that night, and had gone up afterwards to his flat for a game of piquet. Selfe told him with a grin that he was going to lay his servant by the heels to-morrow for blackmail. ‘A smart spry young man to-day,’ he said. ‘Perhaps a bit off colour to-morrow at this time.’ He rang the bell for him to put out the card-table: then saw it was ready, and he forgot that his summons remained unanswered. They played high points and both had drunk a good deal. Selfe lost partie after partie and eventually accused Kennion of cheating. Words ran high and boiled over into blows, and Kennion, in some rough and tumble of wrestling and hitting, picked up a knife from the table and stabbed Selfe in the throat, through jugular vein and carotid artery. In a few minutes he had bled to death…. Then Kennion remembered that unanswered bell, and went tiptoe to Wadham’s room. He found it empty; empty, too, were the other rooms in the flat. Had there been anyone there, his idea was to say he had come up at Selfe’s invitation, and found him dead. But this was better yet: there was no more than a few spots of blood on him, and he washed them in Wadham’s room, emptying the water into his slop-pail. Then leaving the door of the flat open he went downstairs and out.

“He told me this in quite a few sentences, even as I have told it you, and looked up at me with a smiling face.

“‘So what’s to be done next, Venerable Father?’ he said gaily.

“‘Ah, thank God you’ve confessed!’ I said. ‘We’re in time yet to save an innocent man. You must give yourself up to the police at once.’ But even as I spoke my heart misgave me.

“He rose, dusting the knees of his trousers.

“‘What a quaint notion,’ he said. ‘There’s nothing further from my thoughts.’

“I jumped up.

“‘I shall go myself then,’ I said.

“He laughed outright at that.

“‘Oh, no, indeed you won’t,’ he said. ‘What about the seal of confession? Indeed, I rather fancy it’s a deadly sin for a priest ever to think of violating it. Really I’m ashamed of you, my dear Denys. Naughty fellow! But perhaps it was only a joke; you didn’t mean it.’

“‘I do mean it,’ I said. ‘You shall see if I mean it.’ But even as I spoke, I knew I did not. ‘Anything is allowable to save an innocent man from death.’

“He laughed again.

“‘Pardon me: you know perfectly well, that it isn’t,’ he said. ‘There’s one thing in our creed far worse than death, and that is the damnation of the soul. You’ve got no intention of damning yours. I took no risk at all when I confessed to you.’

“‘But it will be murder if you don’t save this man,’ I said.

“‘Oh, certainly, but I’ve got murder on my conscience already,’ he said. ‘One gets used to it very quickly. And having got used to it, another murder doesn’t seem to matter an atom. Poor young Wadham: to-morrow isn’t it? I’m not sure it won’t be a sort of rough justice. Blackmail is a disgusting offence.’

“I went to the telephone, and took off the receiver.

“‘Really this is most interesting’ he said. ‘Walton Street is the nearest police-station. You don’t need the number: just say Walton Street Police. But you can’t. You can’t say “I have a man with me now, Horace Kennion, who has confessed to me that he murdered Selfe.” So why bluff? Besides, if you could do any such thing, I should merely say that I had done nothing of the kind. Your word, the word of a priest who has broken the most sacred vow, against mine. Childish!’

“‘Kennion,’ I said, ‘for the love of God, and for the fear of hell, give yourself up! What does it matter whether you or I live a few years less, if at the end we pass into the vast infinite with our sins confessed and forgiven. Day and night I will pray for you.’

“‘Charming of you,’ said he. ‘But I’ve no doubt that now you will give Wadham full absolution. So what does it matter if he goes into—into the vast infinite at eight o’clock to-morrow morning?’

“‘Why did you confess to me then,’ I asked, ‘if you had no intention of saving him, and making atonement?’

“‘Well, not long ago you were very nasty to me,’ he said. ‘You told me no decent man would consort with me. So it struck me, quite suddenly, only to-day, that it would be pleasant to see you in the most awful hole. I daresay I’ve got Sadic tastes, too, and they are being wonderfully indulged. You’re in torment, you know: you would choose any physical agony rather than to be in such a torture-chamber of the soul. It’s entrancing: I adore it. Thank you very much, Denys.’

“He got up.

“‘I kept my taxi waiting,’ he said. ‘No doubt you’ll be busy to-night. Can I give you a lift anywhere? Pentonville?’

“There are no words to describe certain darknesses and ecstasies that come to the soul, and I can only tell you that I can imagine no hell of remorse that could equal the hell that I was in. For in the bitterness of remorse we can see that our suffering is a needful and salutary experience: only through it can our sin be burned away. But here was a torture blank and meaningless. And then my brain stirred a little, and I began to wonder whether, without breaking the seal of confession, I might not be able to effect something. I saw from my window that the light was burning in the clock-tower at Westminster: the House therefore was sitting, and it seemed possible that without violation I might tell the Home Secretary that a confession had been made me, whereby I knew that Wadham was innocent. He would ask me for any details I could give him, and I could tell him—And then I saw that I could tell him nothing: I could not say that the murderer had gone up with Selfe to his room, for through that information it might be found that Kennion had dined with him. But before I did anything, I must have guidance, and I went to the Cardinal’s house by our Cathedral. He had gone to bed, for it was now after midnight, but in answer to the urgency of my request he came down to see me. I told him without giving any clue, what had happened, and his verdict was what in my heart I knew it would be. Certainly I might see the Home Secretary and tell him that such a confession had been made me, but no word or hint must escape me which could lead to identification. Personally, he did not see how the execution could be postponed on such information as I could give.

“‘And whatever you suffer, my son,’ he said, ‘be sure that you are suffering not from having done wrong, but from having done right. Placed as you are, your temptation to save an innocent man comes from the devil, and whatever you may be called upon to endure for not yielding to it, is of that origin also.’

“I saw the Home Secretary in his room at the House within the hour. But unless I told him more, and he realized that I could not, he was powerless to move.

“‘He was found guilty at his trial,’ he said, ‘and his appeal was dismissed. Without further evidence I can do nothing.’

“He sat thinking a moment: then jumped up.

“‘Good God, it’s ghastly,’ he said. ‘I entirely believe, I needn’t tell you, that you’ve heard this confession, but that doesn’t prove it’s true. Can’t you see the man again? Can’t you put the fear of God into him? If you can do anything at all, which gives me any justification for acting, up till the moment the drop falls, I will give a reprieve at once. There’s my telephone number: ring me up here or at my house at any hour.’

“I was back at the prison before six in the morning. I told Wadham that I believed in his innocence, and I gave him absolution for all else. He received the Holy and Blessed Sacrament with me, and went without flinching to his death.”

Father Denys paused.

“I have been a long time coming to that point in my story,” he said, “which concerns that séance you spoke of, but it was necessary for your understanding of what I am going to tell you now, that you should know all this. I said that these messages and communications from the dead come not from them but from some evil and awful power impersonating them. You answered, I remember, ‘Why drag in the Devil?’ I will tell you.

“When it was over, when the drop on which he stood yawned open, and the rope creaked and jumped, I went home. It was a dark winter’s morning, still barely light, and in spite of the tragic scene I had just witnessed I felt serene and peaceful. I did not think of Kennion at all, only of the boy—he was little more—who had suffered unjustly, and that seemed a pitiful mistake, but no more. It did not touch him, his essential living soul, it was as if he had suffered the sacred expiation of martyrdom. And I was humbly thankful that I had been enabled to act rightly, and had Kennion now, through my agency, been in the hands of the police and Wadham alive, I should have been branded with the most terrible crime a priest can commit.

“I had been up all night, and after I had said my office I lay down on my sofa to get a little sleep. And I dreamed that I was in the cell with Wadham and that he knew I had proof of his innocence. It was within a few minutes of the hour of his death, and I heard along the stone-flagged corridor outside the steps of those who were coming for him. He heard them too, and stood up, pointing at me.

“‘You’re letting an innocent man die, when you could save him,’ he said. ‘You can’t do it, Father Denys. Father Denys!’ he shrieked, and the shriek broke off in a gulp and a gasp as the door opened.

“I woke, knowing that what had roused me was my own name, screamed out from somewhere close at hand, and I knew whose voice it was. But there I was alone in my quiet, empty room, with the dim day peering in. I had been asleep, I saw, for only a few minutes, but now all thought or power of sleep had fled, for somewhere by me, invisible but awfully present, was the spirit of the man whom I had allowed to perish. And he called me.

“But presently I convinced myself that this voice coming to me in sleep was no more than a dream, natural enough in the circumstances, and some days passed tranquilly enough. And then one day when I was walking down a sunny crowded street, I felt some definite and dreadful change in what I may call the psychic atmosphere which surrounds us all, and my soul grew black with fear and with evil imaginings. And there was Wadham coming towards me along the pavement gay and debonair. He looked at me, and his face became a mask of hate. ‘We shall meet often I hope, Father Denys,’ he said, as he passed. Another day I returned home in the twilight, and suddenly, as I entered my room, I heard the creak and strain of a rope, and his body, with head covered by the death-cap, swung in the window against the sunset. And sometimes when I was at my books the door opened quietly and closed again, and I knew he was there. The apparition or the token of it did not come often or perhaps my resistance would have been quickened, for I knew it was devilish in origin. But it came when I was off my guard at long intervals, so that I thought I had vanquished it, and then sometimes I felt my faith to reel. But always it was preceded by this sense of evil power bearing down on me, and I made haste to seek the shelter of the House of Defence which is set very high. And this last Sunday only—”

He broke off, covering his eyes with his hand, as if shutting out some appalling spectacle.

“I had been preaching,” he resumed, “for one of our missions. The church was full, and I do not think there was another thought or desire in my soul but to further the holy cause for which I was speaking. It was a morning service, and the sun poured in through the stained-glass windows in a glow of coloured light. But in the middle of my sermon some bank of cloud drove up, and with it this horrible forewarning of the approach of a tempest of evil. So dark it got that, as I was drawing near the end of my sermon, the lights in the church were switched on, and it leaped into brightness. There was a lamp on the desk in the pulpit, where I had placed my notes, and now when it was kindled it shone full on the pew just below. And there with his head turned upwards towards me, with his face purple and eyes protruding and with the strangling noose round his neck, sat Wadham.

“My voice faltered a second, and I clutched at the pulpit-rail as he stared at me and I at him. A horror of the spirit, black as the eternal night of the lost closed round me, for I had let him go innocent to his death, and my punishment was just. And then like a star shining out through some merciful rent in this soul-storm came again that ray of conviction that as a priest I could not have done otherwise, and with it the sure knowledge that this apparition could not be of God, but of the devil, to be resisted and defied even as we defy with contempt some sweet and insidious temptation. It could not therefore be the spirit of the man at which I gazed, but some diabolical counterfeit.

“And I looked back from him to my notes, and went on with my sermon, for that alone was my business. That pause had seemed to me eternal: it had the quality of timelessness, but I learned afterwards that it had been barely perceptible. And from my own heart I learned that it was no punishment that I was undergoing, but the strengthening of a faith that had faltered.”

Suddenly he broke off. There came into his eyes as he fixed them on the door a look not of fear at all but of savage relentless antagonism.

“It’s coming,” he said to me, “and now if you hear or see anything, despise it, for it is evil.”

The door swung open and closed again, and though nothing visible entered, I knew that there was now in the room a living intelligence other than Father Denys’s and mine, and it affected my being, my self, just as some horrible odour of putrefaction affects one physically: my soul sickened in it. Then, still seeing nothing, I perceived that the room, warm and comfortable just now, with a fire of coal prospering in the grate, was growing cold, and that some strange eclipse was veiling the light. Close to me on the table stood an electric lamp: the shade of it fluttered in the icy draught that stirred in the air, and the illuminant wire was no longer incandescent, but red and dull like the embers in the grate. I scrutinized the dimness, but as yet no material form manifested itself.

Father Denys was sitting very upright in his chair, his eyes fixed and focused on something invisible to me. His lips were moving and muttering, his hands grasped the crucifix he was wearing. And then I saw what I knew he was seeing, too: a face was outlining itself on the air in front of him, a face swollen and purple, with tongue lolling from the mouth, and as it hung there it oscillated to and fro. Clearer and clearer it grew, suspended there by the rope that now became visible to me, and though the apparition was of a man hanged by the neck, it was not dead but active and alive, and the spirit that awfully animated it was no human one, but something diabolical.

Suddenly Father Denys rose to his feet, and his face was within an inch or two of that suspended horror. He raised his hands which held the sacred emblem.

“Begone to your torment,” he cried, “until the days of it are over, and the mercy of God grants you eternal death.”

There rose a wailing in the air: some blast shook the room so that the corners of it quaked, and then the light and the warmth were restored to it, and there was no one there but our two selves. Father Denys’s face was haggard and dripping with the struggle he had been through, but there shone on it such radiance as I have never seen on human countenance.

“It’s over,” he said. “I saw it shrivel and wither before the power of His presence. And your eyes tell me you saw it too and you know now that what wore the semblance of humanity was pure evil.”

We talked a little longer, and he rose to go.

“Ah, I forgot,” he said. “You wanted to know how I could reveal to you what was told me in confession. Horace Kennion died this morning by his own hand. He left with his lawyer a packet to be opened on his death, with instructions that it should be published in the daily Press. I saw it in an evening paper, and it was a detailed account of how he killed Gerald Selfe. He wished it to have all possible publicity.”

“But why?” I asked.

Father Denys paused.

“He gloried in his wickedness, I think,” he said. “He loved it, as I told you, for its own sake, and he wanted everyone to know of it, as soon as he was safely away.”

Edward Frederic Benson (1867 — 1940)